The First and Second World Wars had a profound impact on daily life around the world, and Fife was no exception. In particular, the outbreak of war – and the peace in between – provoked changes to the types of jobs which were done in Fife, and the kind of people who did them.

In this blog post, we’ll explore how the World Wars changed the role that women played in the Fife linoleum industry by examining photographs from our museum collections.

If you would like to learn more, we’ve just installed a temporary display on this subject in our Moments in Time gallery at Kirkcaldy Galleries. This will be on display until the end of August 2023, and you can see it any time during the Galleries’ regular opening hours.

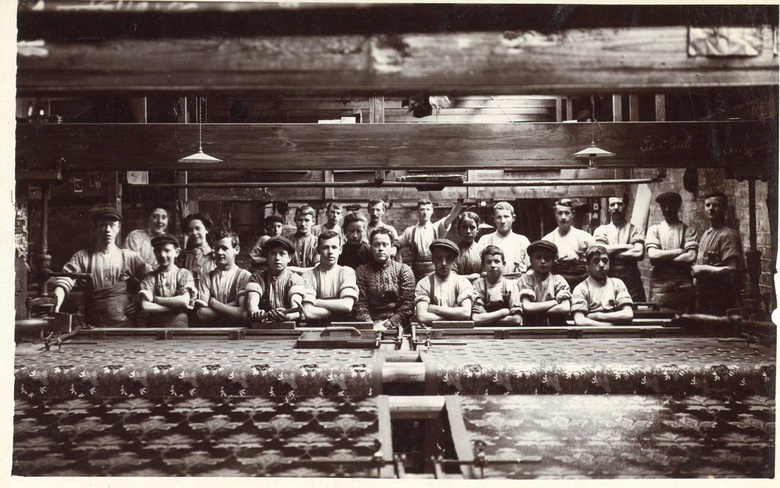

Image: A group of floorcovering workers in the printing loft of the Tayside Floorcloth Company, c.1890 – 1910. (CUPMS1990.0070)

The First World War is often understood as the time when women first entered the workforce en masse, dramatically changing the demographic of – particularly – industrial workplaces. However, that is not to say that women were entirely absent from the workplace before this time.

Women – particularly poor women, women of colour, and women from otherwise marginalised communities, such as recent immigrants – have always had to work to support themselves and their families. Though many felt that certain types of work (or, perhaps, even the idea of work at all) were inappropriate for members of the ‘fairer sex’, eschewing employment was a luxury that few women could afford.

This photograph shows workers in the printing loft at the Tayside Floorcloth Factory, Newburgh, probably at some point between 1890 – 1910. In it, we can see five women and nineteen men and boys. This suggests that, although they were outnumbered, women were still present, and in some cases even represented a significant proportion of the workforce.

We don’t know the specific professions of the people in this photograph. Nonetheless, it does seem likely that they were photographed in the space that they regularly worked, and therefore that this image shows a team largely made up of printers. This indicates that – in at least some workplaces – women were not segregated from men, that they worked in the same spaces as them, and potentially did the same or similar roles.

As we will see in later images, this was not necessarily consistent across the Fife linoleum industry. However, this photograph indicates that conditions like these were not unheard of, even if they were not the norm.

Image: A team of workers in Kirkcaldy in one of Barry, Ostlere and Shepherd’s factories, Kirkcaldy. 1914 – 1918. (KIRMG:1991.0231)

In January 1916, the British Government passed the Military Service Act, which required all men aged between 18 and 41 to join the Armed Forces. This meant that a new workforce had to be found to work in the jobs they left behind.

Skilled, conscription-aged men were replaced with unskilled and semi-skilled women workers, who learnt their new trades on the job. The men who remained were older and often held senior or managerial roles due to their greater lengths of experience.

Across the country, many teams working in factories would have therefore looked something like this. This team made up almost entirely of women, apart from the three men who appear to be above conscription age.

Another notable thing about this image is that some of the women are wearing trousers. This is very unusual; in the vast majority of the photographs in our linoleum collections, working women are shown wearing skirts and dresses. This ‘masculine’ dress-code was again temporarily permitted during the war. Women could dress ‘like men’ while they were doing ‘men’s work’ – but both of these things were understood as strictly temporary measures.

Sadly, we do not know what this team was working on at the time they were photographed. It is possible that they were manufacturing munitions and other goods required by the war effort.

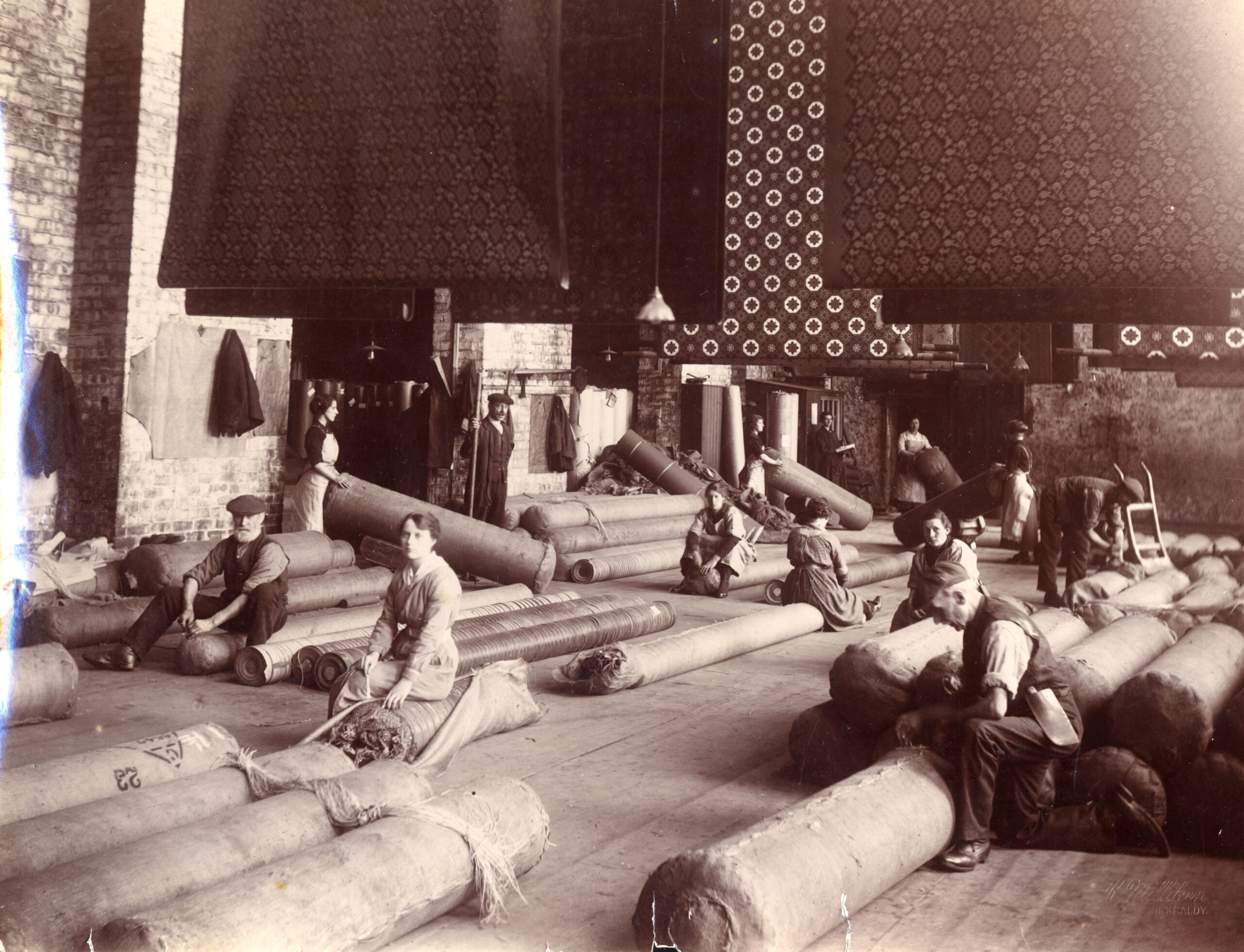

Image: A linoleum despatch room, Kirkcaldy. Of the photographs in our collections which show workers in linoleum factories during WWI, the majority were – like this one – taken in factories operated by Barry, Ostlere and Shepherd in August 1918. (KIRMG:1986.0097)

Many of the women employed in industry during WWI found themselves manufacturing products for the war effort. However, many factories also continued – at least in part – to make whatever they produced during peace time.

This photograph shows workers in the despatch room at one of Barry’s factories, preparing finished linoleum for delivery. From this, we can deduce that linoleum production – for the domestic market – continued through the war, and that women were involved in its manufacture.

Image: Women stoking the boilers in one of Barry, Ostlere and Shepherd’s factories, Kirkcaldy. August 1918. (KIRMG:1986.0095)

Aside from weapons and linoleum, there were also some jobs that simply had to be done regardless of what was being done in the rest of the factory. The women in this photograph are shown stoking the boilers – a task which had to be completed day in, day out, come rain or shine.

Image: Canteen staff at Michael Nairn and Company Limited, Kirkcaldy. 1935. (KIRMG:1983.0633)

Following the end of hostilities, the British government, Trade Unions and other influential groups were eager for working life to get back to normal as soon as possible. This meant women giving up their jobs in favour of the men who had vacated them and, preferably, returning to domestic work (either unpaid in their own homes, or paid in the houses of others).

Nonetheless, through both choice and necessity, some women did remain in the workforce. Usually, women were encouraged into roles which were extensions of the sort of work they would do at home. This included cleaning and, like the canteen workers pictured in this image, cooking.

Image: Clerical staff at one of Barry, Ostlere and Shepherd’s factories, Kirkcaldy. 1920s. This photograph is from a series in our collection which show teams of Barry’s workers. (KIRMG:1980.2620)

There were a few exceptions to this rule, including clerical work. Since the 1880s, administrative tasks had increasingly become associated with women workers. Over the next few decades, this would continue to the point where it became almost quintessential. Even today, we still associate these kind of roles – secretaries, assistants and receptionists – with women.

There are a few reasons for this. Firstly, the typewriter was a new piece of technology, which required previously non-existent skills to operate. As such, women could take up this role without having to face the stigma of having ‘taken a man’s job’.

Secondly, compared to other types of work, administrative tasks were relatively clean and quiet. This dispelled fears from moralists that work was unladylike, and would naturally coarsen women until they were uncivilised (or worse, unattractive to men). A typist could carry out her work and still embody the traits which – in the late 19th and early 20th centuries – were seen as synonymous with womanhood.

Finally: size mattered. As women, on average, had smaller hands than men, it was assumed that they would naturally be more dextrous. Women were naturally suited to typing, because their dainty fingers would be better suited to operating the machine.

Image: Twins Catherine and Janet Fortheringham making inlaid linoleum. Though this photograph dates from c.1959 – 1964 the task was associated with women long before this. (TEMP:2012.4426)

Strangely, the assumption that smaller hands were faster, more dextrous hands may also have led to another job in the linoleum industry becoming the preserve of women.

Throughout the history of the linoleum industry, the production of inlaid linoleum has been a task primarily associated with women. This was a highly skilled process, by which pieces of different coloured linoleum were fitted together to make a pattern. Unlike printed designs, inlaid designs would remain intact regardless of how much the floorcovering was worn down – the colour of each piece went all the way to the back, so the design was much longer lasting.

Image: Workers making fuel tanks for Halifax bombers at one of Michael Nairn and Co. Ltd.’s factories, Kirkcaldy. 1939 – 1945. (TEMP:2012.4431)

When WWII broke out, women once again returned to Kirkcaldy’s factories.

This time, there was a greater focus on producing goods for the war effort. Women working at Nairn’s manufactured fuel tanks for Halifax bombers, as well as munitions.

In 1946, Nairn’s published a book celebrating their workers’ contributions to victory. In this, they stated that perhaps their biggest contribution was the production of anti-gas fabric, which was made into capes and gas-masks. The fabric had to be impregnated with linseed oil, a key ingredient used in the manufacture of linoleum (and which gives the floorcovering its name: ‘lin’ meaning linseed and ‘oleum’ meaning oil). In the book, Nairn’s wrote that this was a decisive factor in the Allies victory. As the Nazis could not manufacture gas-proof textiles in sufficient quantities, they never used gas in air raids for fear of retaliation. As such, they were unable to use a decisive weapon which may have given them the upper hand.

If you would like to learn more about Women, War and Linoleum, we’ve just installed a temporary display on this subject in our Moments in Time gallery at Kirkcaldy Galleries. This will be on display until the end of August 2023, and you can see it any time during the Galleries’ regular opening hours.

_______________________________________________

Flooring the World is a two-year project exploring the history of the Fife linoleum industry. It is funded by the Esmée Fairbairn Collections Fund, which is run by the Museums Association.

![]()