This brilliant photograph below is part of a set of four in our linoleum collection, which document a strike from the worker’s point of view. It shows a group of men gathered around a hand-written sign, which reads: ‘9th day of strike. Morale excellent. We swear to fight till the end.’ Until recently, this was basically everything we knew about these images. As part of the Flooring the World project, we decided to do some research to find out more!

We knew that these photographs showed strikers at a French linoleum factory in the early twentieth century but were unsure exactly when and where they had been taken. We were also not sure how they were connected to our collections, but suspected that they were linked to one of Kirkcaldy’s two largest linoleum companies: Michael Nairn and Company, and Barry, Ostlere and Shepherd.

By the end of the nineteenth century, these companies had come to dominate the Fife (and by extension, the British) linoleum industry. Nairn’s was the town’s oldest firm, and had been growing its reputation since it started producing floorcloth in 1847. Barry’s was a relative newcomer, but – being formed from a merger between several of the town’s smaller firms – had effectively grown to a size where it could compete with Nairn’s by absorbing its own competition. Both firms operated multiple factories across the town: both had premises in Sinclairtown, while Nairn’s dominated the harbour and Victoria Road, and Barry’s surrounded Kirkcaldy’s central railway station.

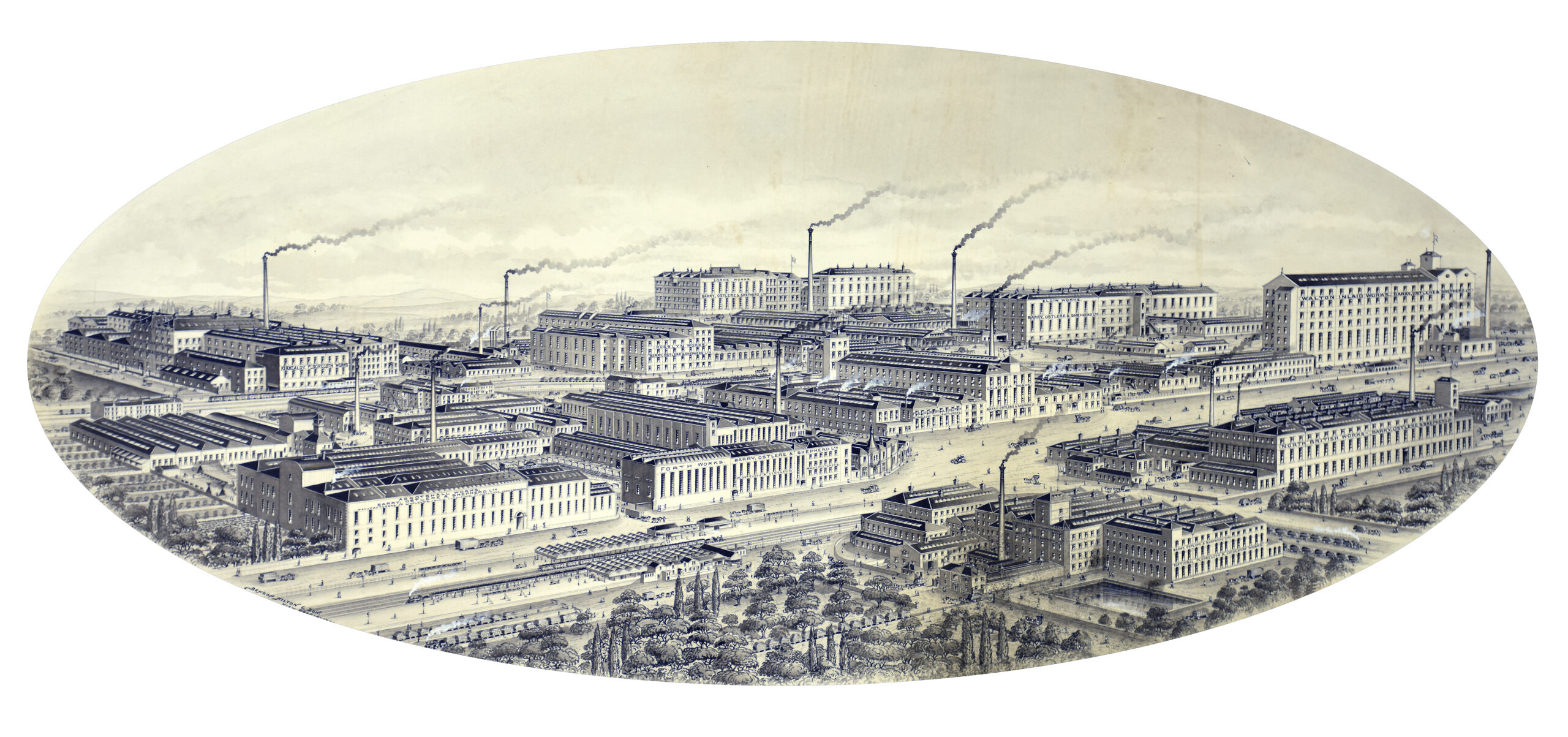

This image shows all the factories operated by Barry, Ostlere and Shepherd in Kirkcaldy, 1905. The factories have been re-arranged to look as if they were all beside each other, but in reality were spread throughout the town.

Outside of Kirkcaldy, both Nairn’s and Barry’s also operated factories overseas, meaning that our strikers could have been employed in a French factory operated by either firm. In order to form a more certain link, and to learn more about our strikers, we’d have to look outside of our collections.

This photograph shows the in-house fire brigade employed at Nairn’s factory at Choisy-Le-Roi, France.

We began by searching Gallica, a database which allows you to search the collections of the French National Library (Bibliothèque National de France, or BnF). Initially, we limited the date range to 1900 – 1929. This was a rough estimate based on the clothes the men were wearing in the photographs; working class men’s fashion is very hard to date as it changes relatively little across a span of decades, but it can still sometimes provide you with an approximate idea. We then searched the database for the word ‘linoleum’ appearing in the same text as the word ‘grève’ (the French for strike).

This resulted in a few results! Sadly, most of these were newspapers or journals which featured adverts for linoleum alongside reports of strikes in other industries. While these were testament to the ubiquity of linoleum in the early 20th century, they did not necessarily help us to answer our strike questions!

Workers playing cards during the strike. The surnames and first initials of some of the strikers are written on the reverse of our prints. In future, it may be possible to learn more about them by using family history research skills.

However, one result did look promising. In an issue of L’Humanité – the official journal of the French Communist Party – dated to 7 March 1923, mentioned a strike at a linoleum factory in Le Houlme, Normandy, operated by La Compagnie Rouennaise de Linoleum. But what was the link between this strike, and our collections?

The answer lies in that busy time at the end of the 19th century when Nairn’s and Barry’s were consolidating their power. Barry, Ostlere and Shepherd was officially formed in 1899, by a merger between John Barry, Ostlere and Company, Shepherd and Beveridge, and the Kirkcaldy Linoleum Company – all of whom had been producing floorcoverings in the shadow of the older and more established Nairn’s. There was however a fourth company included in Barry’s DNA: a little Normandy venture called La Compagnie Rouennaise de Linoleum (CRdL).

The CRdL was established in 1897, two years before it became part of Barry’s. At the time of the merger, it employed approximately 150 people, which rose to around 500 by 1950. It is therefore likely that their workforce at the time of the strike was somewhere in the middle of this range. The image below shows 87 men gathered outside the factory gates, indicating that a significant proportion of the factory’s workers decided to take action against their employers.

2023 marks 100 years since the workers of Le Houlme went on strike!

The strikers’ demands were centred around their pay. Their employers had offered to increase their pay in the summer months, but not the winter, and this had been rejected. However, it is also possible that the connection with Fife may have added to the workers’ grievances. A report in our collection written in the 1950s by T J Cavanagh, one of Barry’s managers, noted that the French factory often had to make do with out-of-date equipment. When new machines were purchased, these were prioritised for Kirkcaldy who then sent their cast-offs to Normandy. It is possible that the feeling that the French factory was something of an after-thought may have been present in the 1920s, and contributed to the feeling of discontent among the workers.

We don’t know how long the strike went on for after the 11th day captured in the last photograph above. The next issue of L’Humanité reported that the Rouennaise strikers had been victorious – but this came just a few days after the original report of 7 March. This means it’s quite likely that it took a few days for the strikers to get in touch with L’Humanité – or perhaps they turned to the Communist party to increase pressure once the strike had gone on for longer than anticipated.

In either case, the workers were victorious! Their employers agreed to give them a pay rise of 175 cents per hour, holiday pay and to ‘keep all their pre-strike advantages’. This last is slightly ambiguous, though it was common for striking workers to request agreement in writing that they would not be prejudiced against for striking when they returned to work. It is possible that this clause was included to guarantee this kind of protection.

The CRdL continued to manufacture floorcoverings until 1968, some five years after Barry’s ceased production in Kirkcaldy (though the company survived until 1969 in Staines Middlesex, and until 1978 in Newburgh, Fife). Like many of Fife’s factories, it was fell victim to the falling demand for linoleum as alternative floorcoverings became cheaper to buy and easier to maintain.

_____________________________________________

Flooring the World is a two-year project exploring the history of the Fife linoleum industry. It is funded by the Esmée Fairbairn Collections Fund, which is run by the Museums Association.

![]()