This brilliant photograph below is part of a set of four in our linoleum collection, which document a strike from the worker’s point of view. It shows a group of men gathered around a hand-written sign, which reads: ‘9th day of strike. Morale excellent. We swear to fight till the end.’ Until recently, this was basically everything we knew about these images. As part of the Flooring the World project, we decided to do some research to find out more!

We knew that these photographs showed strikers at a French linoleum factory in the early twentieth century but were unsure exactly when and where they had been taken. We were also not sure how they were connected to our collections, but suspected that they were linked to one of Kirkcaldy’s two largest linoleum companies: Michael Nairn and Company, and Barry, Ostlere and Shepherd.

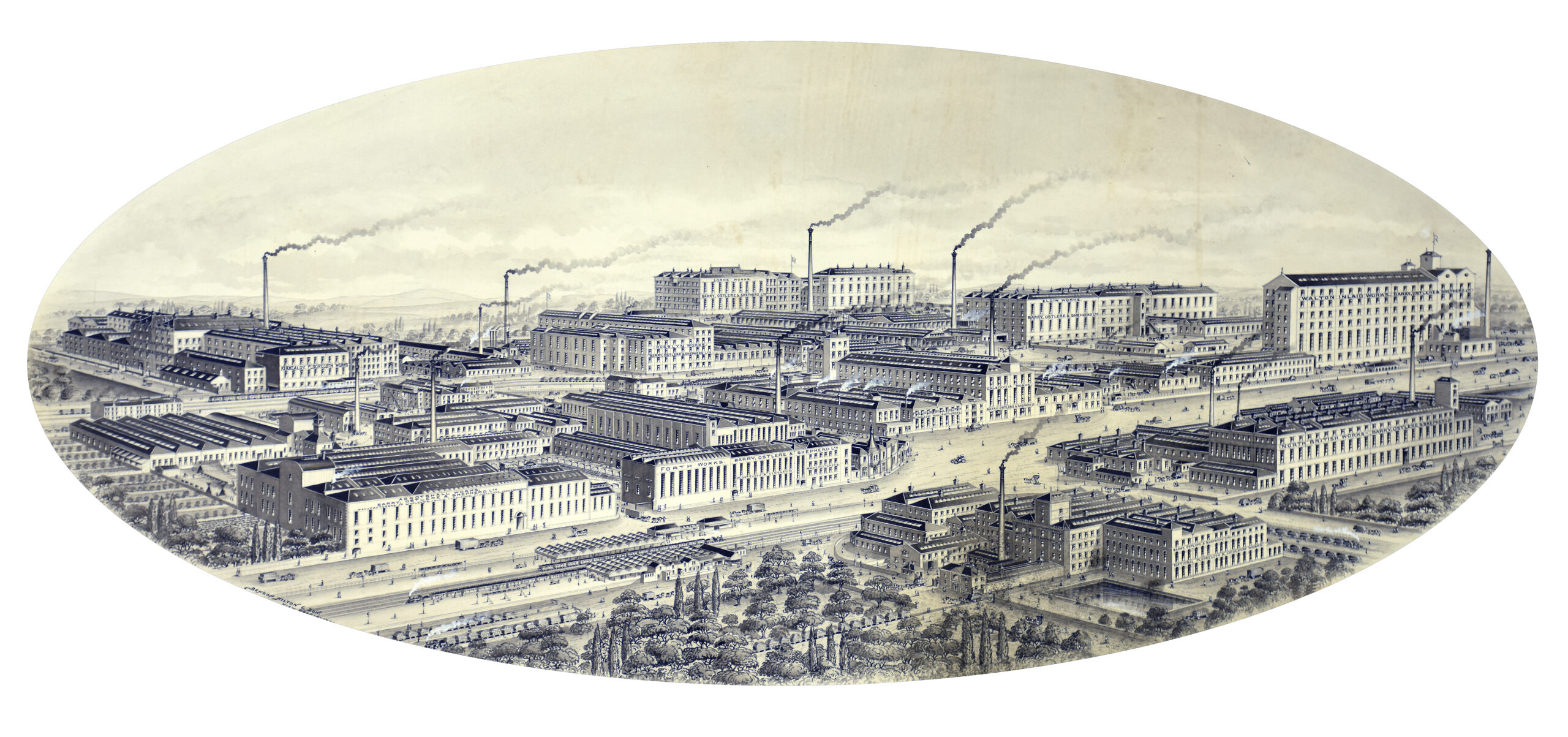

By the end of the nineteenth century, these companies had come to dominate the Fife (and by extension, the British) linoleum industry. Nairn’s was the town’s oldest firm, and had been growing its reputation since it started producing floorcloth in 1847. Barry’s was a relative newcomer, but – being formed from a merger between several of the town’s smaller firms – had effectively grown to a size where it could compete with Nairn’s by absorbing its own competition. Both firms operated multiple factories across the town: both had premises in Sinclairtown, while Nairn’s dominated the harbour and Victoria Road, and Barry’s surrounded Kirkcaldy’s central railway station.

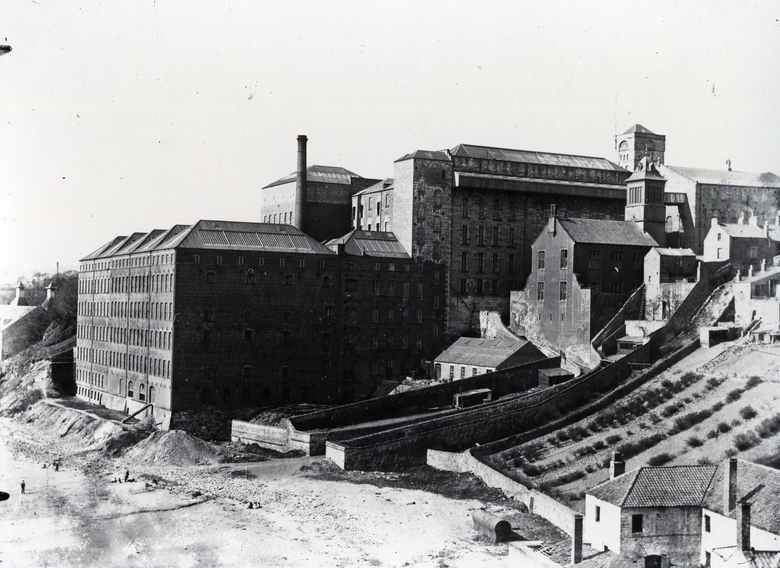

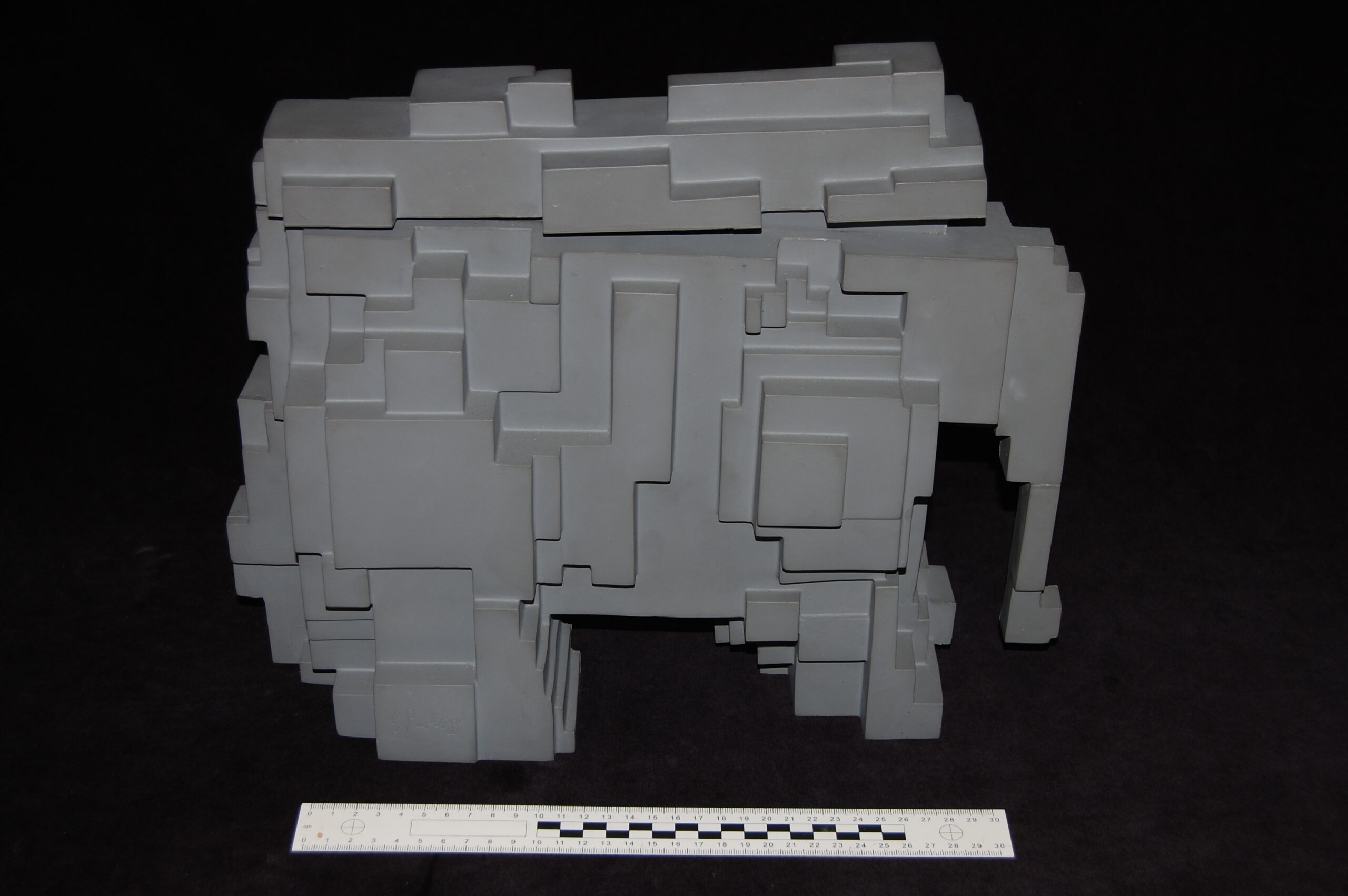

This image shows all the factories operated by Barry, Ostlere and Shepherd in Kirkcaldy, 1905. The factories have been re-arranged to look as if they were all beside each other, but in reality were spread throughout the town.

Outside of Kirkcaldy, both Nairn’s and Barry’s also operated factories overseas, meaning that our strikers could have been employed in a French factory operated by either firm. In order to form a more certain link, and to learn more about our strikers, we’d have to look outside of our collections.

This photograph shows the in-house fire brigade employed at Nairn’s factory at Choisy-Le-Roi, France.

We began by searching Gallica, a database which allows you to search the collections of the French National Library (Bibliothèque National de France, or BnF). Initially, we limited the date range to 1900 – 1929. This was a rough estimate based on the clothes the men were wearing in the photographs; working class men’s fashion is very hard to date as it changes relatively little across a span of decades, but it can still sometimes provide you with an approximate idea. We then searched the database for the word ‘linoleum’ appearing in the same text as the word ‘grève’ (the French for strike).

This resulted in a few results! Sadly, most of these were newspapers or journals which featured adverts for linoleum alongside reports of strikes in other industries. While these were testament to the ubiquity of linoleum in the early 20th century, they did not necessarily help us to answer our strike questions!

Workers playing cards during the strike. The surnames and first initials of some of the strikers are written on the reverse of our prints. In future, it may be possible to learn more about them by using family history research skills.

However, one result did look promising. In an issue of L’Humanité – the official journal of the French Communist Party – dated to 7 March 1923, mentioned a strike at a linoleum factory in Le Houlme, Normandy, operated by La Compagnie Rouennaise de Linoleum. But what was the link between this strike, and our collections?

The answer lies in that busy time at the end of the 19th century when Nairn’s and Barry’s were consolidating their power. Barry, Ostlere and Shepherd was officially formed in 1899, by a merger between John Barry, Ostlere and Company, Shepherd and Beveridge, and the Kirkcaldy Linoleum Company – all of whom had been producing floorcoverings in the shadow of the older and more established Nairn’s. There was however a fourth company included in Barry’s DNA: a little Normandy venture called La Compagnie Rouennaise de Linoleum (CRdL).

The CRdL was established in 1897, two years before it became part of Barry’s. At the time of the merger, it employed approximately 150 people, which rose to around 500 by 1950. It is therefore likely that their workforce at the time of the strike was somewhere in the middle of this range. The image below shows 87 men gathered outside the factory gates, indicating that a significant proportion of the factory’s workers decided to take action against their employers.

2023 marks 100 years since the workers of Le Houlme went on strike!

The strikers’ demands were centred around their pay. Their employers had offered to increase their pay in the summer months, but not the winter, and this had been rejected. However, it is also possible that the connection with Fife may have added to the workers’ grievances. A report in our collection written in the 1950s by T J Cavanagh, one of Barry’s managers, noted that the French factory often had to make do with out-of-date equipment. When new machines were purchased, these were prioritised for Kirkcaldy who then sent their cast-offs to Normandy. It is possible that the feeling that the French factory was something of an after-thought may have been present in the 1920s, and contributed to the feeling of discontent among the workers.

We don’t know how long the strike went on for after the 11th day captured in the last photograph above. The next issue of L’Humanité reported that the Rouennaise strikers had been victorious – but this came just a few days after the original report of 7 March. This means it’s quite likely that it took a few days for the strikers to get in touch with L’Humanité – or perhaps they turned to the Communist party to increase pressure once the strike had gone on for longer than anticipated.

In either case, the workers were victorious! Their employers agreed to give them a pay rise of 175 cents per hour, holiday pay and to ‘keep all their pre-strike advantages’. This last is slightly ambiguous, though it was common for striking workers to request agreement in writing that they would not be prejudiced against for striking when they returned to work. It is possible that this clause was included to guarantee this kind of protection.

The CRdL continued to manufacture floorcoverings until 1968, some five years after Barry’s ceased production in Kirkcaldy (though the company survived until 1969 in Staines Middlesex, and until 1978 in Newburgh, Fife). Like many of Fife’s factories, it was fell victim to the falling demand for linoleum as alternative floorcoverings became cheaper to buy and easier to maintain.

_____________________________________________

Flooring the World is a two-year project exploring the history of the Fife linoleum industry. It is funded by the Esmée Fairbairn Collections Fund, which is run by the Museums Association.

![]()

Our linoleum collections consist of over 5,000 objects, documents and photographs, covering over 170 years of history. For this story, we’re heading all the way back into linoleum’s pre-history, to its origins in the Kirkcaldy floorcloth industry.

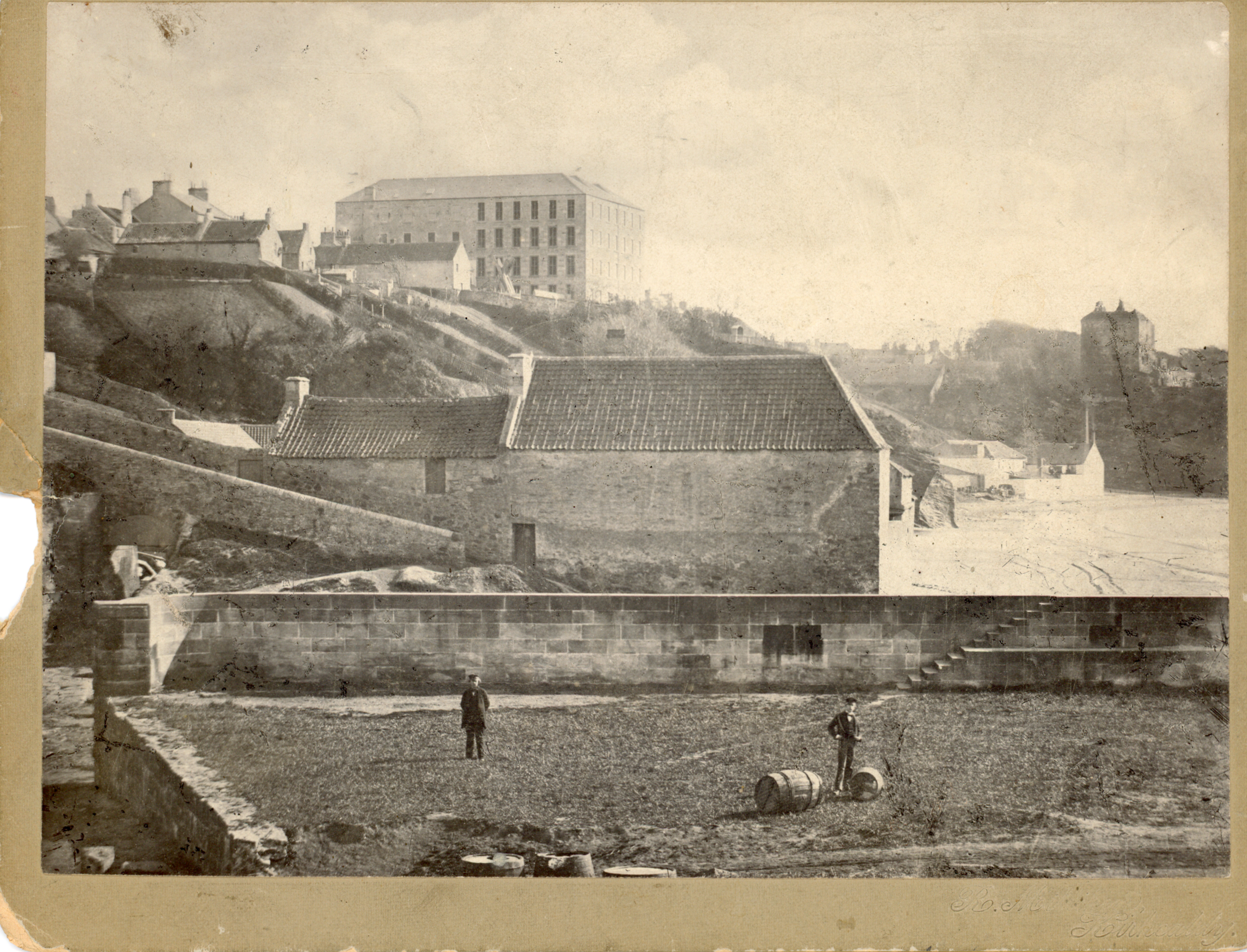

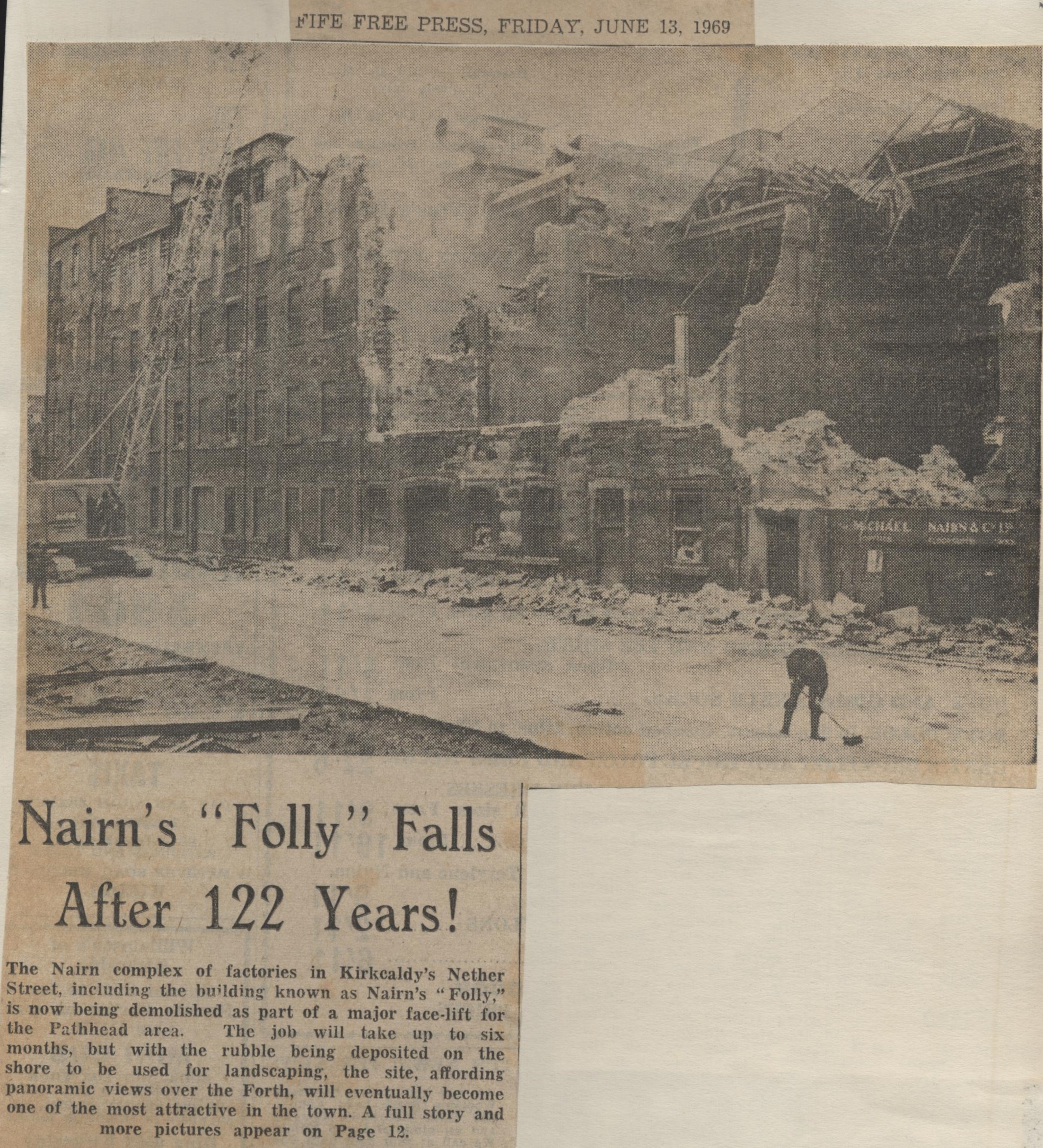

The first floorcloth factory in Scotland was built by Michael Nairn in the Pathhead area of Kirkcaldy. Known colloquially as ‘Nairn’s Folly’, this massive factory was the first stepping-stone in Nairn’s evolution from a small-scale canvas manufacturer to one of the most prolific producers of floorcoverings in the world.

A view of the beach below Ravenscraig castle. Nairn’s Folly is the large building on the top of the cliffs.

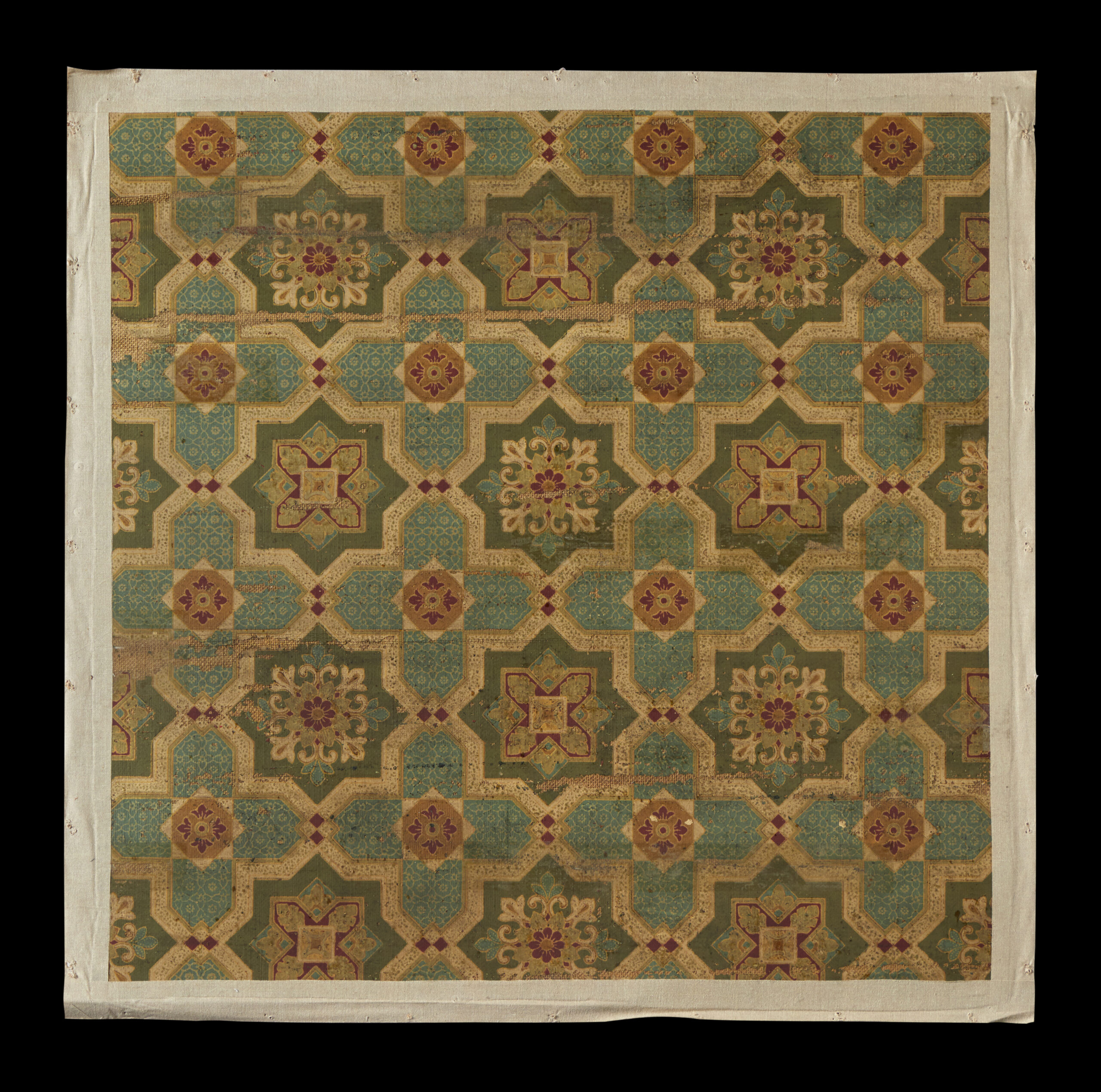

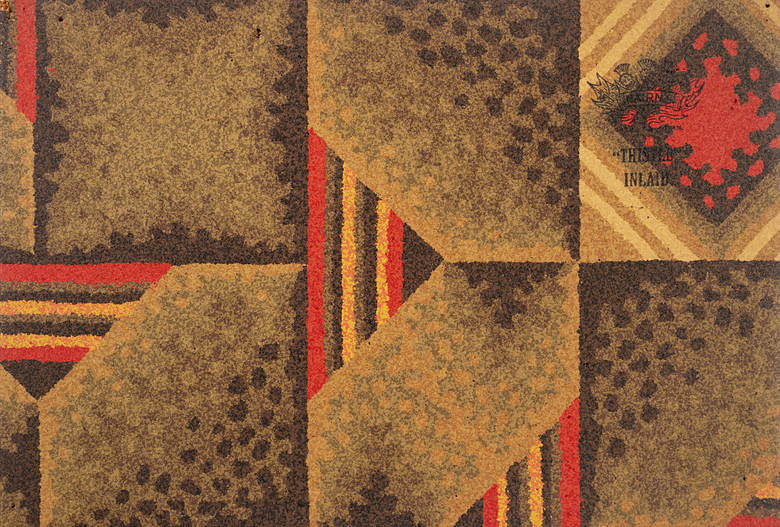

Floorcloth itself had existed for centuries; the earliest known reference to it in the UK is in the inventory of a house called Denham Hall in 1736! It was similar to linoleum, and was made of many of the same ingredients and using similar processes. A paste made from resins, cork dust, wood flour and coloured pigments was painted onto a canvas backing. These layers were built up on either side of the canvas, so that each side was smooth and waterproof. A patterned design would then be printed on the ‘top’ side. These could then be used, like rugs or carpets, to cover dirt, wood or stone floors.

For the first 30 years of their foray into floorcoverings, Nairn’s focused exclusively on floorcloth. From 1877, they produced both floorcloth and linoleum, until the former dwindled away in the first few decades of the 20th century.

A floorcloth banner from our collection. The first image shows the design painted on the ‘bottom’ of floorcloth. The second shows the printed ‘top’, which would become the back of the banner when it was carried.

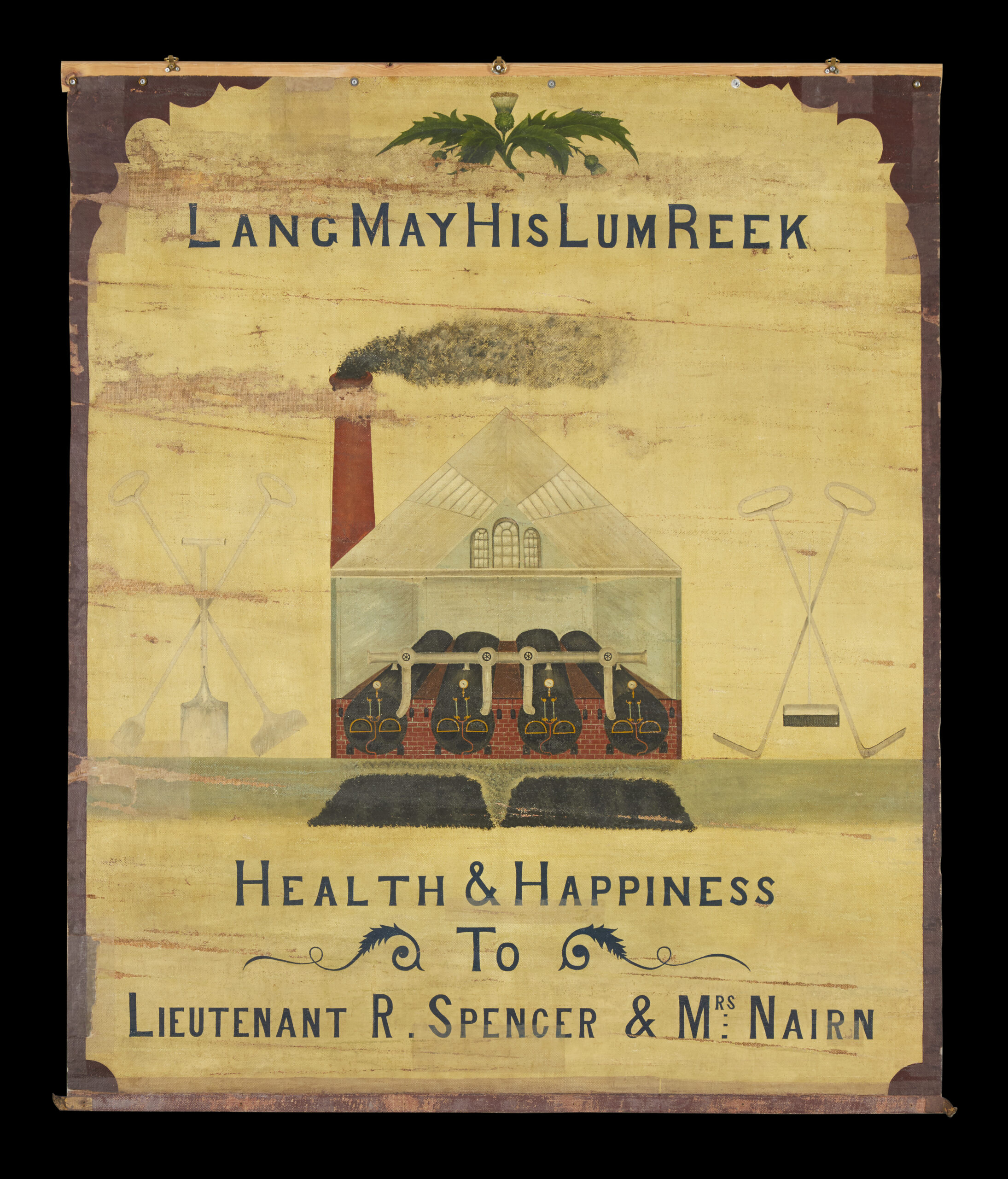

For Nairn’s however, floorcloth wasn’t just for floors. From the late 19th century up until the First World War, it was used to create a series of hand-painted banners, which were carried in processions by the workers. The patterned ‘top’ side of the floorcloth became the back of the banner, and the plain ‘bottom’ side was painted with a design and slogan. Usually, these praised the Nairn family or the products made by the company.

We know from photographs and secondary sources that dozens of different banners were made. Today, only five are known to survive – all in our collection. We are not currently aware of any other banners like this in the world, so it is possible that these are the only five in existence.

A floorcloth banner from our collection, created in 1907.

This banner was created by the engineers and fireman from Nairn’s Folly floorcloth works to commemorate the wedding of Robert Spencer Nairn on 6 July 1907. To mark the occasion, the Nairn family organised a workers’ excursion to their estate in Rankeilour (near Cupar, Fife). This would have been the first time this banner was carried.

A photograph showing the Nairn’s workers marching with floorcloth banners during their 1903 excursion.

At the beginning of the day, Nairn’s workers gathered at each of their places of work across the town. The first group then set off from the Canvas works, marching towards Nether Street where their colleagues from the Floorcloth Works would join them as they passed Mid Street. An article in the Fife Free Press (dated 13 July 1907) records that all the banners in our collection were made and carried by the Floorcloth Works group, who also wore floorcloth caps and sashes.

After a short interval, the Linoleum workers would join in behind them, led by a foreman carrying a sword. The Trades Band played at the front of the procession, and the Pathhead Band played at the back.

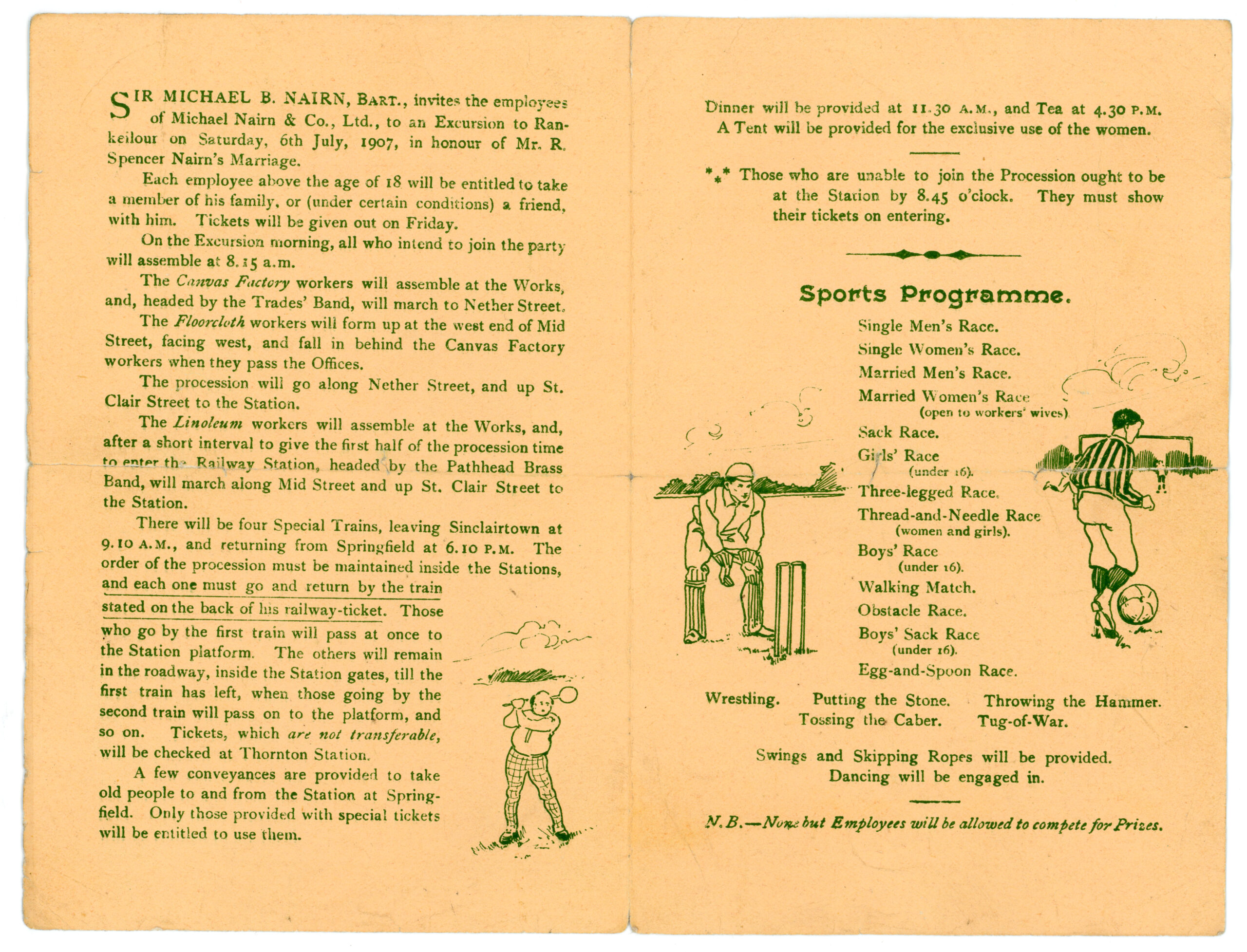

The itinerary produced for the 1907 Summer Excursion.

All workers then boarded special trains at Sinclairtown station, where they were taken north to Rankeilour. In total, over 2,400 people attended, as each worker was permitted to bring a family member or friend along with them.

On arrival there, they enjoyed an early lunch (served at 11:30), followed by dinner at 16:30. In between, they played the sort of games you’d expect at a summer fete (including the sack race and the egg and spoon race) and a Highland games (including a caber toss).

The Nairn’s workers at Rankeilour during their 1905 Summer Excursion.

We know from other excursion itineraries in our collection that these excursions happened on at least two other occasions during this decade – first in 1901, and next in 1905. However, it is possible that this trip to Rankeilour may have been the last in which our floorcloth banners were used.

This banner was conserved in 2020, and is currently on display at Kirkcaldy Galleries.

We know that this banner was carried along with ‘Lang May His Lum Reek’ in 1907. From conservation in 2020, we know that this banner had the date on it repainted each time it was carried. As the date visible was the last time it was updated, it is possible that this was its final outing. If this is the case, then it is likely that our ‘Lang May His Lum Reek’ banner was also only carried on this single trip.

Interested in seeing our floorcloth banners in person?

‘First in the Field’ is part of our permanent displays in Kirkcaldy Galleries and can be seen in the Moments in Time gallery, opposite the café.

‘Lang May His Lum Reek’ will be going on display as part of the Flooring the World exhibition, which will open at Kirkcaldy Galleries on 25 November 2023.

It is also possible to see two of the three remaining banners at our collections store in Bankhead, Glenrothes. You can make an appointment to see them by e-mailing museums.enquiries@onfife.com

_______________________________________________

Flooring the World is a two-year project exploring the history of the Fife linoleum industry. It is funded by the Esmée Fairbairn Collections Fund, which is run by the Museums Association.

![]()

To celebrate the acquisition of a rare Malcolm IV penny, the coronation of King Charles III, and Dunfermline’s new City status (granted on 20 May 2022), this blog gives a small glimpse into the fascinating history of early Scottish coins and the royal history of Dunfermline through OnFife museums’ coin collection.

The first Scottish king to issue coins was David I. In 1136, King David I took control of the city of Carlisle and the surrounding silver mines, and thus began to mint the first ever Scottish currency – a penny coin. At first, David’s coins imitated English ones (depicting the king’s bust, facing forward). His later coins took a different design, with the king’s bust facing sideways.

During his reign, David granted Dunfermline the status of a royal burgh and raised the status of the priory to an Abbey. He endowed it richly and brought stonemasons from Durham Cathedral to build it. David I is buried in Dunfermline Abbey Church. David I coins are very rare and there are no examples in our collection.

Image: Malcolm IV penny front and back (from around 1153-1165). Uncertain mint . FIFER:2023.1023 Acquired from the Treasure Trove Unit, 2023. Discovered by a metal detectorist in Aberdour area. Purchase of the coin has been made possible with the support of the Art Fund and National Fund for Acquisitions.

Malcolm IV (1141-1165), grandson of David I, was nicknamed ‘the Maiden’ because of his young age. Malcolm only reigned for 12 years and died at the age of 24. His pennies are therefore very rare.

The coin depicted above is the fifth single find recorded in Scotland. Unlike most other Scottish kings (up until the 1390s), Malcolm had this coin modelled in the style of English kings (depicting a front-facing portrait of the king, rather than a side-facing bust). Politically, Scotland was in a stronger position at the time than England – perhaps the design of the penny was chosen to reflect that?

Malcolm IV is buried in Dunfermline Abbey, just like his grandfather David I and his great-grandparents, Malcolm III and Queen Margaret.

Image: William I penny (from around 1195-1205) . Minted by Walter of Perth . KIRMG:1980.0414

William I (c. 1142-1214) was Malcolm’s brother. It is thought that he was the first monarch to use the Lion Rampant (a red lion on a yellow background) as his Royal emblem, hence his nickname, The Lion. William I was the first Scottish king to produce silver pennies in a relatively large quantity. These coins were in use both in England and in Scotland.

William continued to favour Dunfermline Abbey during his reign although he is not buried there. Instead, he is buried in Arbroath Abbey which he founded in 1178.

William was succeeded by his son, Alexander II, but there are no examples of Alexander II coins in OnFife museums’ collection.

Image: Alexander III penny (from around 1280-1292) . Possibly minted in Berwick. KIRMG:1980.0364

Alexander III (1241-1286) second coinage does not bear the name of the moneyer and the mint. Instead, the legend REX SCOTORVM (Latin for ‘King of Scots’) was written on reverse. It is thought that fifty million coins were produced during this coinage. Scotland was prospering at the time and Scottish coins were accepted throughout Europe and are often found in hoards on the continent.

Alexander III visited Dunfermline Abbey in 1250 to see the remains of Queen Margaret. Alexander died in a fall from his horse while riding near Kinghorn, Fife on 19 March 1286. A monument commemorates the approximate location of his death on the edge of a rocky embankment. Similarly to many of his ancestors, Alexander III was also buried in Dunfermline Abbey.

Image: Robert the Bruce penny (from around 1320-1329) . Uncertain mint. KIRMG: 1980.0413

Alexander III left no heirs, leading to a period of instability. In 1306, Robert I known as Robert the Bruce (1274-1329), great-grandson of David I, finally seized the throne and gradually begun to free Scotland from English rule. By the early 1320s, he had enough control (including of Berwick, one of the main mints at the time) to produce coins again in Scotland. All of Robert I coins are rare, reflecting the turbulent period of his reign.

After his death, Robert’s body was brought to Dunfermline from Cardross in possibly the largest funeral procession ever seen in Scotland. His mausoleum is in Dunfermline Abbey Church.

Image: David II groat (from around 1358-1367). Edinburgh mint. KIRMG: 1980.1801

King David II (1324-1371), son of Robert the Bruce, was born in Dunfermline Abbey. He spent most of his early reign in exile in France or in captivity in England. In 1357, a large ransom was agreed to be paid to England and David II was released. At first, David II was keen to demonstrate Scotland’s growing prosperity – this included introducing new currencies such as groat (fourpence, depicted above). Following the loss of Berwick to the English in 1333 it is thought that these coins were minted in Edinburgh.

However, due to the rising costs of gold and silver and economic difficulties (including struggles to back-pay his ransom), the weight of David II’s coins was reduced in 1367. This led to the gradual separation of the values of the currencies of England and Scotland.

David died very suddenly in Edinburgh and was buried in Holyrood Abbey. He left no children and was succeeded by Robert II (1316-1390), the son of David´s half-sister Marjorie Bruce, and her husband, Walter Stewart.

Image: Robert II groat (from around 1371-1390) . Edinburgh mint . KIRMG:1980.0417

Robert II, the first Scottish king of the Stewart line, was the grandson of Robert the Bruce. He acted as regent during part of the period of David II’s imprisonment and succeeded to the throne after David’s death. His coinage was kept at the same standard and style as that of David’s.

Robert held court in Dunfermline until 1389 when he retired to Dundonald Castle. He is buried at Scone Abbey.

Image: Robert III groat (from around 1390-1403). Edinburgh mint. KIRMG:1980.3089

During Robert III reign, several new innovations to the coinage were introduced. First, the coins adopted the English style of the facing bust (as depicted above). Because of the rising cost of silver, his smaller denominations (the pence and halfpence) were minted in alloy known as billion. This led to his coins being outlawed in England in 1411.

Robert III (1337-1406) was the first Scottish monarch to use the image of St Andrew on his coins (on lion and demi-lion currencies). These coins are very rare and are not represented in our collection.

Robert III was buried at Paisley Abbey (which was founded by his family) but his wife, Annabella Drummond (c 1350-1401), was buried at Dunfermline Abbey.

Image: James I groat (from around 1425-1437). Uncertain mint. KIRMG:1980.1794

James I was the youngest son of Robert III and was born in Dunfermline in 1394. He was imprisoned in England until 1424 and very few coins were minted until his return to Scotland. In an attempt to compensate for the rising price of silver and Scotland’s economic struggles, James I groat (depicted above) was revalued from fourpence to sixpence and its weight was slightly raised. This change reflects the political instability in Scotland at the time. James was assassinated at Perth in 1437 and was buried in Perth Charterhouse, a monastery which he had founded.

There are no examples of James II and James III coins in OnFife museums’ collection which is why their coinage is not mentioned here.

Image: James IV plack (from around 1496-1513). Edinburgh mint. KIRMG:1980.3232

James IV (1473-1513) continued to issue placks (fourpence, depicted above) and half placks (twopence) – new currencies introduced by his father, James III. James IV was the most successful of all the Stewart rulers of Scotland. During his 25-year reign, royal income doubled, the crown exercised firm control over the Scottish church and royal administration was extended to the Highlands and islands. James occasionally resided in Dunfermline and invested in improvements to Dunfermline Palace.

Image: James V bawbee (from around 1539-1542). Edinburgh mint. KIRMG:1980.3095

Bawbee (depicted above) was a coin valued at sixpence. It was introduced by King James V (1512-1542) and remained in use until the 1700s. The name of the coin comes from the name of James V’s mint-master’s estate, Sillebawby, a farm in Burntisland in Fife.

A carved stone bearing the arms of James V can still be seen in the Dunfermline Abbey museum. It is thought to have decorated his royal apartment in Dunfermline. One of his favourite residencies in Scotland was Falkland Palace in Fife, however. This is also where he died, aged thirty.

Image: Mary’s nonsunt, front and back (1558) . Unknown mint. KIRMG:1980.1805

Mary Queen of Scots (1542-1587) coinage gives a colourful overview of her reign – the design of her coins changed during various regencies, marriages, wars with England and the alliance with France. New denominations were also introduced, including a twelve penny groat or ‘Nonsunt’. The name ‘Nonsunt’ comes from the Biblical inscription in Latin on the reverse of the coin: Iam non sunt duo sed una caro (They are no longer two but one flesh). The coin depicted above was issued when Mary married Francis II of France. Their monogram can be seen on front of the coin.

Mary visited Dunfermline several times but had no close ties with the royal burgh.

Image: James VI 12 shillings, front and back (from around 1603-1625). Unknown mint . KIRMG:1980.1824. On the reverse of the coin, the arms of England (and France) are in the first and fourth quarter, the rampant lion of Scotland in the second quarter, and the harp of Ireland in the third.

After Mary’s son, King James VI of Scotland (1566-1625) became King James I of England in 1603, Scotland started to use the same coinage standard as England again. The coin depicted above, was produced after his accession to the English throne and is inscribed “James by the Grace of God, King of Great Britain, France, Ireland” (in Latin).

James and his wife Anne greatly invested in the development of Dunfermline Palace in the 1580s, but royal interest in Dunfermline waned when James and Anne left for London in 1603, and the palace fell into disrepair.

Image: James VI gold unit (from around 1637-1642). Nicholas Briot coinage, Edinburgh. KIRMG:1980.3354

James VI’s son Charles I was born at Dunfermline Palace in 1600. He was the last king to be born in Scotland. Charles was crowned in 1626 in Westminster Abbey but at the insistence of the Scots, his Scottish coronation took place separately, in 1633, in Edinburgh. After the ceremony, the king toured Linlithgow, Stirling, Dunfermline, and Falkland palaces.

In 1636, Charles I made Nicholas Briot (who was the Chief Engraver to the Royal Mint), master of the Scottish Mint in Edinburgh. Briot replaced Scotland’s gold and silver hammered coinage with machine made milled coinage which is why this coin has a more circular shape.

Charles believed that the king had a divine right to rule. This is also reflected in his coinage which bears a Latin inscription, “I am set over them, that I may be profitable to them.” Charles subjects had different views, however, and the King was executed in 1649.

Scotland still produced its own native coinage until the Acts of Union in 1707, but Dunfermline’s royal status was lost with the death of the last Dunfermline-born king.

_____________________

All coins mentioned in this article are on display at Dunfermline Carnegie Library and Galleries 6 May – 2 July 2023. OnFife coin collection at Bankhead Collections Centre, Glenrothes can be seen by appointment. To make a booking, please contact us at museums.enquiries@onfife.com.

The First and Second World Wars had a profound impact on daily life around the world, and Fife was no exception. In particular, the outbreak of war – and the peace in between – provoked changes to the types of jobs which were done in Fife, and the kind of people who did them.

In this blog post, we’ll explore how the World Wars changed the role that women played in the Fife linoleum industry by examining photographs from our museum collections.

If you would like to learn more, we’ve just installed a temporary display on this subject in our Moments in Time gallery at Kirkcaldy Galleries. This will be on display until the end of August 2023, and you can see it any time during the Galleries’ regular opening hours.

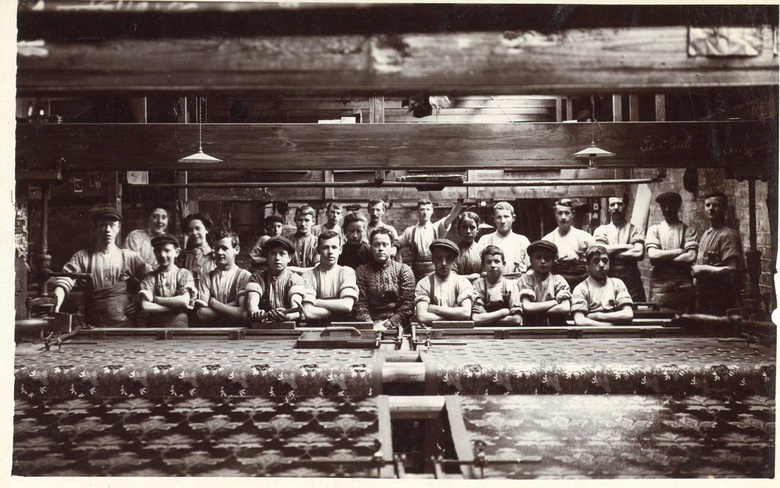

Image: A group of floorcovering workers in the printing loft of the Tayside Floorcloth Company, c.1890 – 1910. (CUPMS1990.0070)

The First World War is often understood as the time when women first entered the workforce en masse, dramatically changing the demographic of – particularly – industrial workplaces. However, that is not to say that women were entirely absent from the workplace before this time.

Women – particularly poor women, women of colour, and women from otherwise marginalised communities, such as recent immigrants – have always had to work to support themselves and their families. Though many felt that certain types of work (or, perhaps, even the idea of work at all) were inappropriate for members of the ‘fairer sex’, eschewing employment was a luxury that few women could afford.

This photograph shows workers in the printing loft at the Tayside Floorcloth Factory, Newburgh, probably at some point between 1890 – 1910. In it, we can see five women and nineteen men and boys. This suggests that, although they were outnumbered, women were still present, and in some cases even represented a significant proportion of the workforce.

We don’t know the specific professions of the people in this photograph. Nonetheless, it does seem likely that they were photographed in the space that they regularly worked, and therefore that this image shows a team largely made up of printers. This indicates that – in at least some workplaces – women were not segregated from men, that they worked in the same spaces as them, and potentially did the same or similar roles.

As we will see in later images, this was not necessarily consistent across the Fife linoleum industry. However, this photograph indicates that conditions like these were not unheard of, even if they were not the norm.

Image: A team of workers in Kirkcaldy in one of Barry, Ostlere and Shepherd’s factories, Kirkcaldy. 1914 – 1918. (KIRMG:1991.0231)

In January 1916, the British Government passed the Military Service Act, which required all men aged between 18 and 41 to join the Armed Forces. This meant that a new workforce had to be found to work in the jobs they left behind.

Skilled, conscription-aged men were replaced with unskilled and semi-skilled women workers, who learnt their new trades on the job. The men who remained were older and often held senior or managerial roles due to their greater lengths of experience.

Across the country, many teams working in factories would have therefore looked something like this. This team made up almost entirely of women, apart from the three men who appear to be above conscription age.

Another notable thing about this image is that some of the women are wearing trousers. This is very unusual; in the vast majority of the photographs in our linoleum collections, working women are shown wearing skirts and dresses. This ‘masculine’ dress-code was again temporarily permitted during the war. Women could dress ‘like men’ while they were doing ‘men’s work’ – but both of these things were understood as strictly temporary measures.

Sadly, we do not know what this team was working on at the time they were photographed. It is possible that they were manufacturing munitions and other goods required by the war effort.

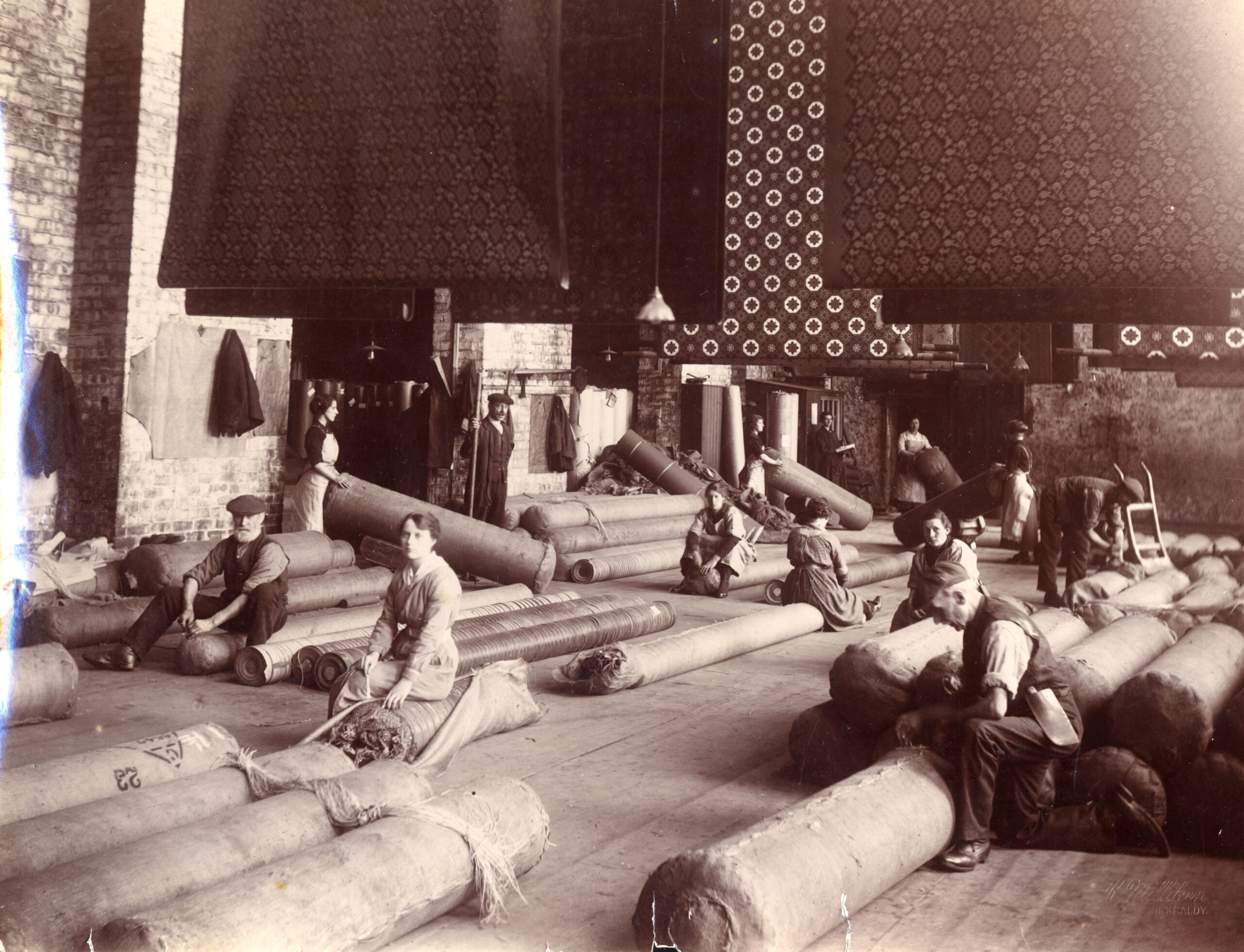

Image: A linoleum despatch room, Kirkcaldy. Of the photographs in our collections which show workers in linoleum factories during WWI, the majority were – like this one – taken in factories operated by Barry, Ostlere and Shepherd in August 1918. (KIRMG:1986.0097)

Many of the women employed in industry during WWI found themselves manufacturing products for the war effort. However, many factories also continued – at least in part – to make whatever they produced during peace time.

This photograph shows workers in the despatch room at one of Barry’s factories, preparing finished linoleum for delivery. From this, we can deduce that linoleum production – for the domestic market – continued through the war, and that women were involved in its manufacture.

Image: Women stoking the boilers in one of Barry, Ostlere and Shepherd’s factories, Kirkcaldy. August 1918. (KIRMG:1986.0095)

Aside from weapons and linoleum, there were also some jobs that simply had to be done regardless of what was being done in the rest of the factory. The women in this photograph are shown stoking the boilers – a task which had to be completed day in, day out, come rain or shine.

Image: Canteen staff at Michael Nairn and Company Limited, Kirkcaldy. 1935. (KIRMG:1983.0633)

Following the end of hostilities, the British government, Trade Unions and other influential groups were eager for working life to get back to normal as soon as possible. This meant women giving up their jobs in favour of the men who had vacated them and, preferably, returning to domestic work (either unpaid in their own homes, or paid in the houses of others).

Nonetheless, through both choice and necessity, some women did remain in the workforce. Usually, women were encouraged into roles which were extensions of the sort of work they would do at home. This included cleaning and, like the canteen workers pictured in this image, cooking.

Image: Clerical staff at one of Barry, Ostlere and Shepherd’s factories, Kirkcaldy. 1920s. This photograph is from a series in our collection which show teams of Barry’s workers. (KIRMG:1980.2620)

There were a few exceptions to this rule, including clerical work. Since the 1880s, administrative tasks had increasingly become associated with women workers. Over the next few decades, this would continue to the point where it became almost quintessential. Even today, we still associate these kind of roles – secretaries, assistants and receptionists – with women.

There are a few reasons for this. Firstly, the typewriter was a new piece of technology, which required previously non-existent skills to operate. As such, women could take up this role without having to face the stigma of having ‘taken a man’s job’.

Secondly, compared to other types of work, administrative tasks were relatively clean and quiet. This dispelled fears from moralists that work was unladylike, and would naturally coarsen women until they were uncivilised (or worse, unattractive to men). A typist could carry out her work and still embody the traits which – in the late 19th and early 20th centuries – were seen as synonymous with womanhood.

Finally: size mattered. As women, on average, had smaller hands than men, it was assumed that they would naturally be more dextrous. Women were naturally suited to typing, because their dainty fingers would be better suited to operating the machine.

Image: Twins Catherine and Janet Fortheringham making inlaid linoleum. Though this photograph dates from c.1959 – 1964 the task was associated with women long before this. (TEMP:2012.4426)

Strangely, the assumption that smaller hands were faster, more dextrous hands may also have led to another job in the linoleum industry becoming the preserve of women.

Throughout the history of the linoleum industry, the production of inlaid linoleum has been a task primarily associated with women. This was a highly skilled process, by which pieces of different coloured linoleum were fitted together to make a pattern. Unlike printed designs, inlaid designs would remain intact regardless of how much the floorcovering was worn down – the colour of each piece went all the way to the back, so the design was much longer lasting.

Image: Workers making fuel tanks for Halifax bombers at one of Michael Nairn and Co. Ltd.’s factories, Kirkcaldy. 1939 – 1945. (TEMP:2012.4431)

When WWII broke out, women once again returned to Kirkcaldy’s factories.

This time, there was a greater focus on producing goods for the war effort. Women working at Nairn’s manufactured fuel tanks for Halifax bombers, as well as munitions.

In 1946, Nairn’s published a book celebrating their workers’ contributions to victory. In this, they stated that perhaps their biggest contribution was the production of anti-gas fabric, which was made into capes and gas-masks. The fabric had to be impregnated with linseed oil, a key ingredient used in the manufacture of linoleum (and which gives the floorcovering its name: ‘lin’ meaning linseed and ‘oleum’ meaning oil). In the book, Nairn’s wrote that this was a decisive factor in the Allies victory. As the Nazis could not manufacture gas-proof textiles in sufficient quantities, they never used gas in air raids for fear of retaliation. As such, they were unable to use a decisive weapon which may have given them the upper hand.

If you would like to learn more about Women, War and Linoleum, we’ve just installed a temporary display on this subject in our Moments in Time gallery at Kirkcaldy Galleries. This will be on display until the end of August 2023, and you can see it any time during the Galleries’ regular opening hours.

_______________________________________________

Flooring the World is a two-year project exploring the history of the Fife linoleum industry. It is funded by the Esmée Fairbairn Collections Fund, which is run by the Museums Association.

![]()

From the 1950s, linoleum faced one of the greatest challenges in its history – one which influenced the way the product was marketed for decades.

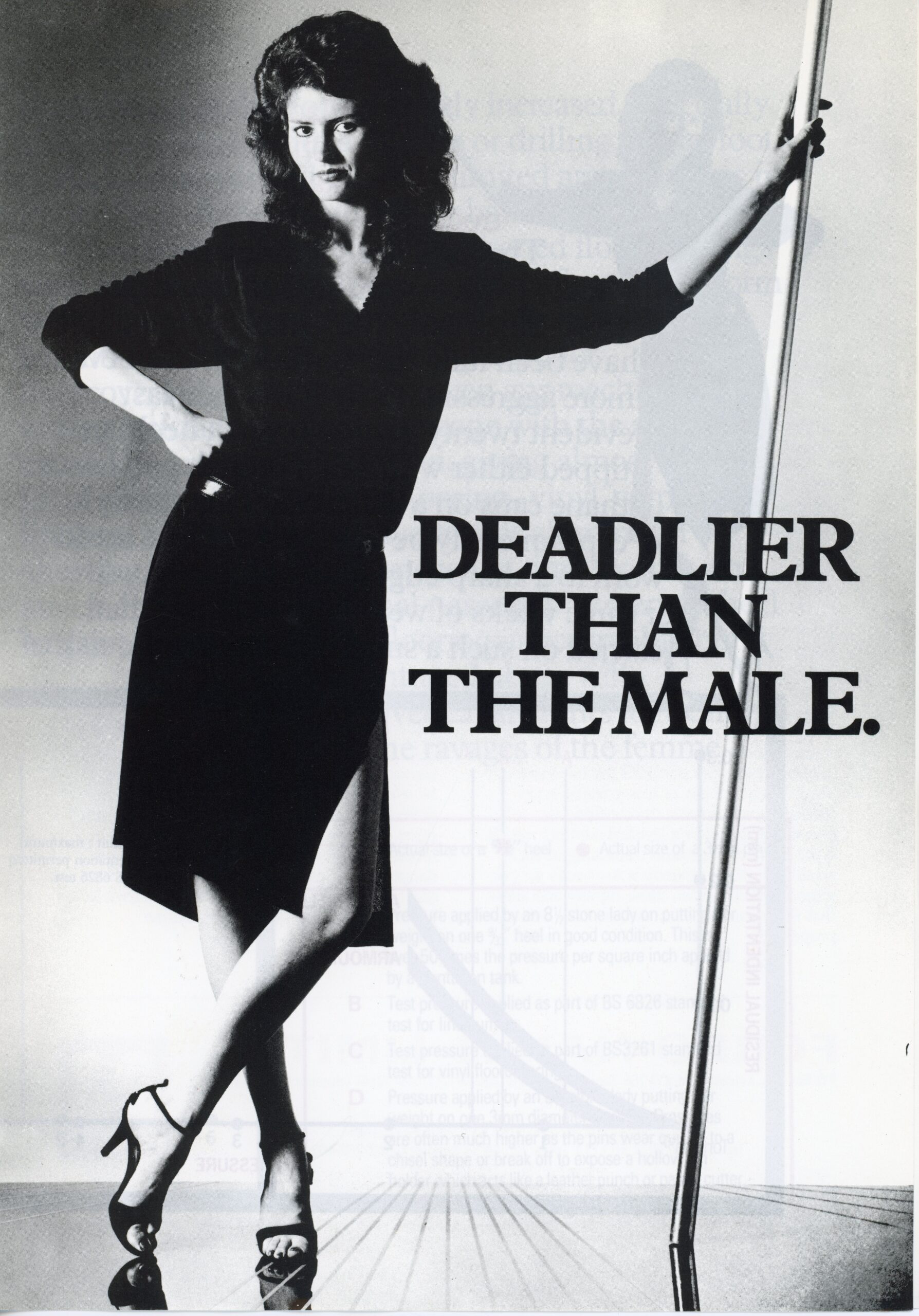

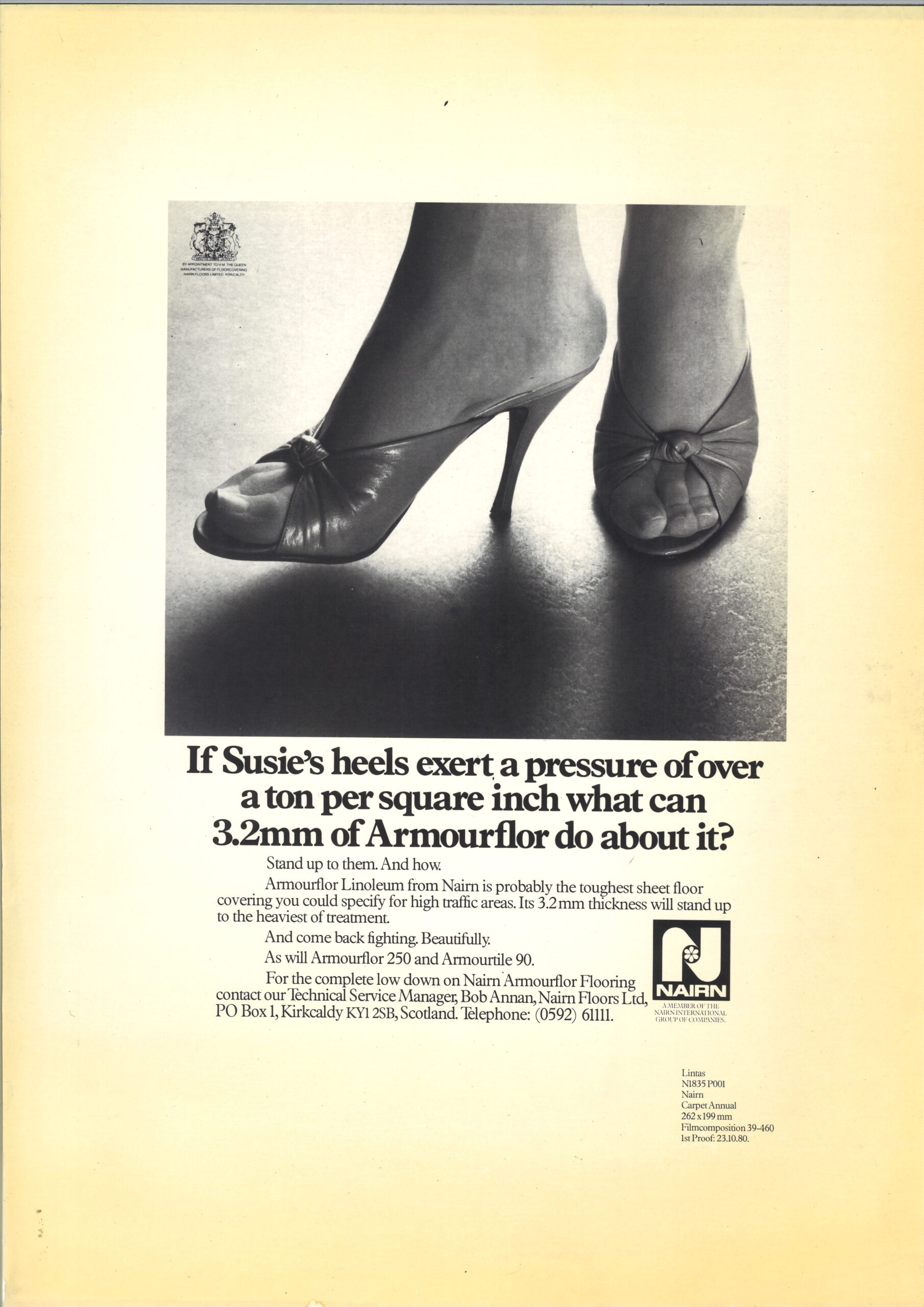

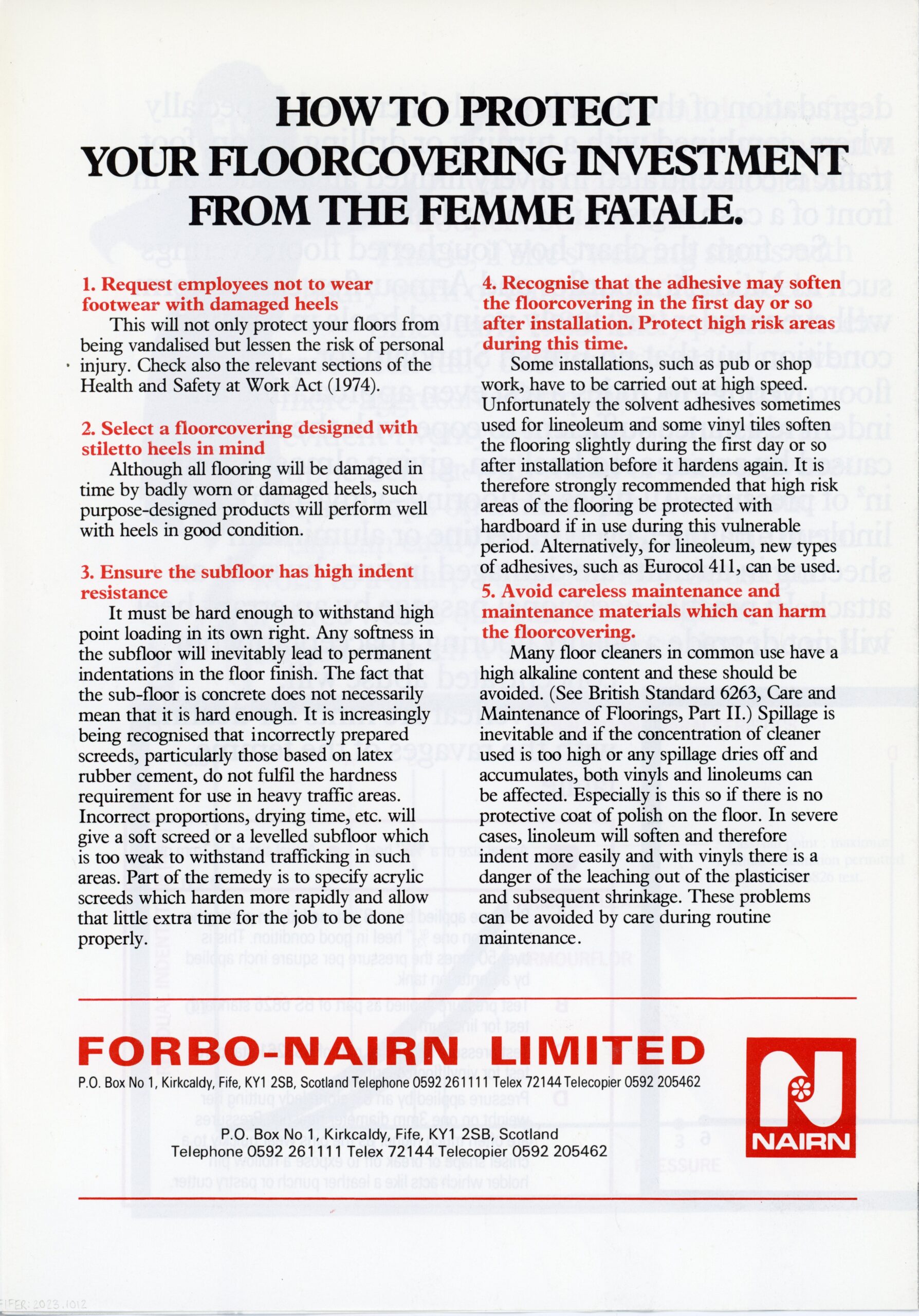

Let’s start with a image. A black and white photograph of a woman, standing in a non-descript space. Below her is a slogan: Deadlier than the male. But the words don’t refer to the woman, or to her fluffy hair, or her dark dress, or her direct stare. Instead, they’re directed at what’s on her feet: a pair of strappy, open-toe shoes with a short, thin heel.

Image: Promotional booklet produced by Forbo-Nairn, c.1985.

The stiletto heel was first developed in the 1930s, though their original inventor is disputed. The design was made possible by the use of a thin metal core within the heel which gave it its strength and structure (as well as its name – a stiletto was a thin dagger which came into use in 15th century Italy). In the 1950s, this design was popularised French designers Andre Perugia and Roger Viver. By the 1960s, the stiletto heel had spread across Europe and North America, and was synonymous with style, sex appeal and glamour.

However, the rise of the stiletto was not just a concern for the fashion conscious; in the mid-twentieth, stiletto heels were on the minds (and in the nightmares) of every linoleum manufacturer in the world.

Heeled shoes had been walking over linoleum for as long as it had existed. The difference here was that the thin heel of the stiletto concentrated the wearer’s weight in a far smaller area, exerting a far greater pressure on the floor beneath. It is estimated that a stiletto heel worn by a person weighing 65kg exerts twelve times the pressure of a four-tonne elephant standing on one foot.

These high pressures meant that wearers left small indentations in linoleum floors as they walked. The increased popularity of stilettos, alongside the ubiquity of linoleum in both public and private buildings, meant that the damage was apparent to everyone. As lino’s reputation came under fire, both manufacturers and consumers became concerned about the longevity of the previously reliable floorcovering.

As such, manufacturers began to fight back with advertising. Theoretically, these stressed improvements to linoleum in the face of the new challenge of stilettos. In practice, while demonising the shoes they also laid the blame squarely at the heeled feet of the women who wore them.

Stilettos had very quickly become symbols of femininity to the point, even acting as a shorthand for signalling gender; for example, Minnie Mouse is essentially identical to Mickey, except for her high heels. Damage done by heels then, was damage done by women. Linoleum under attack from not just a shoe, but from an entire gender.

The rise in the popularity of stiletto heels came at a time when women were entering the workforce en masse. They were working in larger numbers, and in more diverse roles than ever before. At the same time as many were becoming concerned about the impact of shoes on linoleum, others were worried about the impact of this social change on the established order of things.

Let’s return to our advert. On the reverse, it includes a series of tips for protecting floorcoverings from the femme fatale. While most of these concern the floorcoverings themselves, the first tip simply suggests that stilettos be banned from the workplace. Dress-codes like this had been prevalent in offices since the 1950s, and were always enforced with the express desire of protecting floorcoverings. However, as stilettos had become very much symbolic of women as a whole, perhaps we can also see this trend in the context of anxieties over women’s liberation. Was the desire to have no stilettos in the workplace also partly a desire to have less women in the workplace too?

It would be wrong to suggest that linoleum advertising was in any way leading the charge when it came to sexism. However, these adverts can be seen as artefacts of a general perception of gender which – though it did not raise eyebrows at the time – now seems both dated and problematic.

________________________________________________

Flooring the World is a two-year project exploring the history of the Fife linoleum industry. It is funded by the Esmée Fairbairn Collections Fund, which is run by the Museums Association.

![]()

As we reach the end of the first year of the Flooring the World project, curator Lily shares some of the things the project has achieved over the last twelve months.

February

Image: Block made up of layers of ink. FIFER:2022.0184

One of the first things I did when I joined OnFife was visit the archive at the Forbo Factory on Den Road. The firm, initially as Michael Nairn’s and then to Forbo through a series of name-changes and mergers, has been producing floorcoverings in Kirkcaldy since 1847. They have offered their entire archive to us as part of the project, and I’ve spent a lot of time this year working through their amazing objects, documents and photographs deciding what to bring into our collections.

I accessioned this strange object after my first visit. It’s a block made up of layers of ink used to print designs on linoleum. It was cut from a spot under the floorboards in one of the – now demolished – Nairn’s printing lofts – over the decades, waste ink had dripped between the boards and built-up layer by layer. This block is a literal slice of history.

Image: RMS Queen Elizabeth, made out of linoleum. FIFER:2022.0147

Another new addition to the collections was this brilliant picture made of out linoleum. It shows the ship the Queen Elizabeth at sea, and was probably made in the late 1930s. We don’t know who made it, but suspect it was probably created in Fife. Read our post on this curious object to find out more.

I also got the change to visit Newburgh, another key site in the story of the Fife linoleum industry. While the factory buildings which made up the Tayside Floorcloth Company complex are now gone, the imprint of the industrial is still visible in the town. One place you can find a trace of it is in the Laing Museum – the patterned floor of the museum is original printed floorcloth which was laid in the 1890s.

Image: Floorcloth at Laing Museum, Newburgh

March

Image: Page from a pattern book. FIFER:2022.0150

In March, using funds provided by the Friends of Kirkcaldy Galleries, we had some of the objects in our collection photographed. Some of these – like the pattern book above – were new arrivals from the Forbo archive. Others, like the medal below, had been in our collection for some time. Medals like these were awarded to manufacturers at World’s Fairs and Expositions during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Perhaps the most famous of these was the Great Exhibition in London, 1851 – sometimes known as the ‘Crystal Palace’. Nairn’s were unlucky at this fair, but took notes on the products displayed by other floorcovering manufacturers to improve their processes. The research paid off, and for years afterwards they regularly returned home from these trips with a brace of accolades.

Image: Linoleum medal, brass, Allgemeine Deutsche Patent und Mustedrschutz Ausstellung in Frankfurt A. M. 1881, M Nairn & Co. TEMP:2011.1529

April

Image: Floorcloth banner. KIRMG:1983.0078

April saw the long-awaited return of one of our gorgeous floorcloth banners to Kirkcaldy Galleries. This banner went out for conservation before the start of lockdown in 2020 but, in order to keep everyone safe, it wasn’t possibly to reinstall it until 2022. The banner is one of five known to exist – all of which are in our collections. It was created by workers at Nairn’s at some point between 1900 – 1905, with a design painted on the plain underside of a printed floorcovering. Its conservation was generously funded by the Friends of Kirkcaldy Galleries.

Image: Back of the floorcloth banner. KIRMG:1983.0078

I also changed over the display in our Moments In Time case in Kirkcaldy galleries. At the beginning of the project I set myself the (perhaps overly ambitious goal) of changing the objects in this case once every three months. I began with a selection of objects from the Forbo archive, including the paint block I mentioned above.

May

In May I had the opportunity to share the project with other people working in museums across Scotland. I gave a presentation at the Scottish Museum Federation’s annual conference, introducing them to the wonderful world of linoleum and sharing the work that had been done so far. I also got the chance to show National Trust for Scotland curators Antonia Laurence-Allen and Emma Inglis (curators for Edinburgh and East, and Glasgow, respectively) around our stores. We spoke about the fascinating history of linoleum in Scottish houses, and talked about places where it can still be seen in situ today.

June

Image: Linoleum lent to V&A Dundee. FIFER:2022.0167

In June we had a visit from staff from V and A Dundee, who selected some samples of linoleum to go in their exhibition Plastics: Remaking Our World. Linoleum is not a synthetic plastic, but a biodegradable substance made of natural materials derived from plants. The objects were included to help illustrate some of the first materials which were designed to solve the same problems which were later resolved by plastic – perhaps by revisiting these older materials we can find an answer to the problems plastic in its turn has caused. These samples will be coming back to us soon, but you can still see some gorgeous inlaid lino in their Scottish Design gallery.

Image: Linoleum sample on long-term loan to V&A Dundee. FIFER:2017.0016

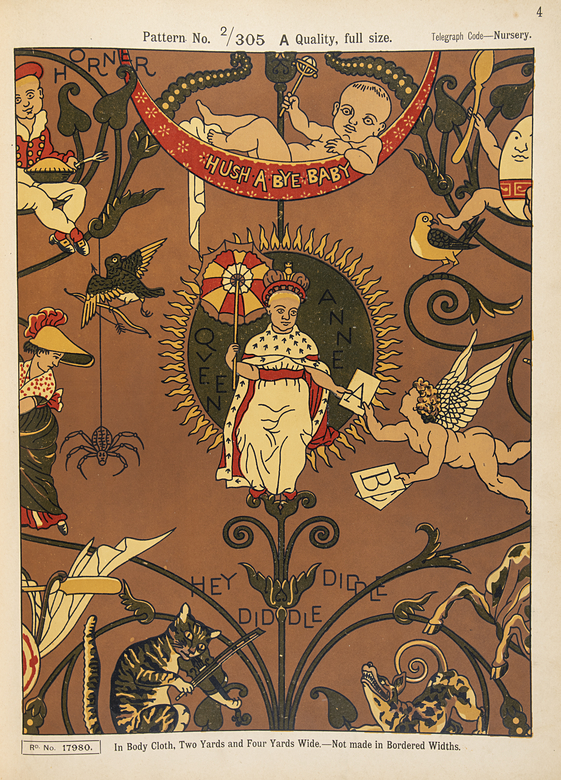

I also got a chance to write up some research I’d been doing, inspired by the many beautiful linoleum designs in our collections which were clearly intended for children’s rooms. Most of the patterns in our collections – be they in books or samples – are fairly neutral, and would be suited to any space. The exception is a small group of very intricate, complicated designs featuring characters from nursery rhymes. I wanted to find out more, and if you do to, then you can click here to read all about it.

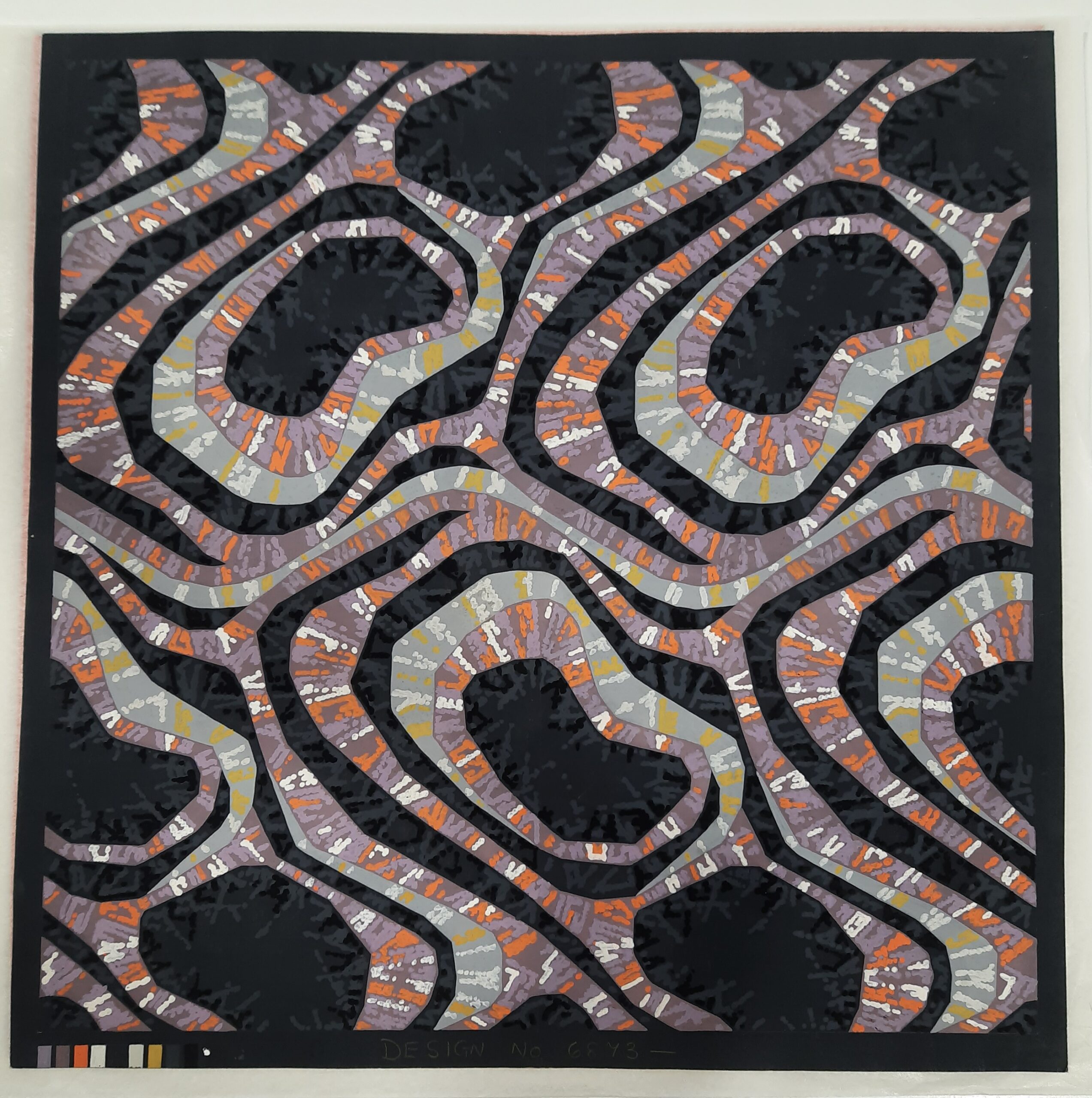

Image: In a pattern book produced by the Kirkcaldy Linoleum Company, 1876 – c.1900. FIFER:2022.0150

July

Shh! In July I was invited along to talk about linoleum for a forthcoming TV programme. I can’t tell you too much about it yet, but watch this space!

By July, it was already time to change the Moments In Time case. This time I opted to go for a selection of objects and photographs which told the story of Kirkcaldy linoleum in the 1960s – a dark decade which saw the loss of much of the city’s industry. I wanted to try something a little bit different, so supported this display with a playlist of songs which were popular at the time, to help conjure up memories of times gone by. You can listen along here.

Image: 1960s linoleum.

August

In August I was lucky enough to record the first oral history of the project. This involves going out to meet people who worked – or who had relatives who worked – in the linoleum industry, and speaking to them about their working life. These recordings become a part of our collection, and can be accessed by anyone interested in the industry to help them to learn more about the lived experience of those would made the linoleum industry possible.

For my first oral history recording, I spoke with someone who designed patterns from linoleum at Newburgh, first for the Tayside Floorcloth Company, and then for Barry Staines. They also kindly donated some of their hand-painted designs, which were created between 1959 and 1969.

I am hoping to record even more oral histories in 2023. I’d like to speak with anyone and everyone who worked (or who had family members who worked) with linoleum, or anyone who has a story to tell me about the industry in Fife. I’d be particularly keen to hear from those who have memories of the industry in Falkland, as this is somewhat underrepresented in our collections.

If you’d like to learn more, please get in touch using the contact details at the bottom of this post.

September

Image: Newburgh Ancestry and Family History Society visit.

In September, we welcome the Newburgh Ancestry and Family History Society to our collections stores at Bankhead. The group were there to see a selection of objects relating to Newburgh, including some of the wonderful photographs in our collection showing the town’s linoleum industry.

October

Patented!

I was invited to speak about the history of lino on Patented, a podcast produced by History Hit. She chatted with host Dallas Campbell about how linoleum was invented, and how – via a ground-breaking legal trial – it made its way to Kirkcaldy.

We also welcomed the first of our linoleum store tours! This meant welcoming two groups to take a guided tour around our collections store at Bankhead, before giving them the chance to get up close and personal with a selection of objects, documents and photographs from our linoleum collection. This included a chance to see the newly conserved Paolozzi elephant (more about them in December!).

Finally, I changed over the Moments in Time case in Kirkcaldy Galleries to feature a display about the in-house fire brigades employed by linoleum factories. You can learn more about them in this blog post.

Image: Collections store tour.

November

November saw another round of tours, with yet more visitors getting to see our collections in the flesh. We’re looking forward to running more of these in 2023, so if you’re interested in coming along please get in touch using the contact details at the bottom of this article.

I also collected another load of boxes from the Forbo Archive – these were the last to enter our collection this year. In total, we accessioned over a nine hundred objects, documents and photographs from the Forbo Archive in 2022 – and there is lots more to come in 2023!

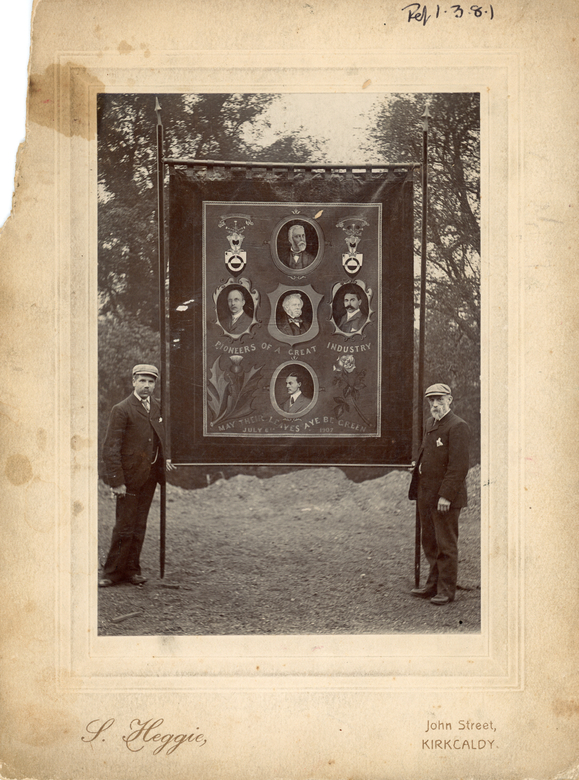

One of my favourite things from the archive is this photograph of two men holding a floorcloth banner, probably dating to c.1900-1909. The banner is now lost, so this photograph is our only record of it.

Images: Photograph of workers with a floorcloth banner. TEMP:2012.4439

December

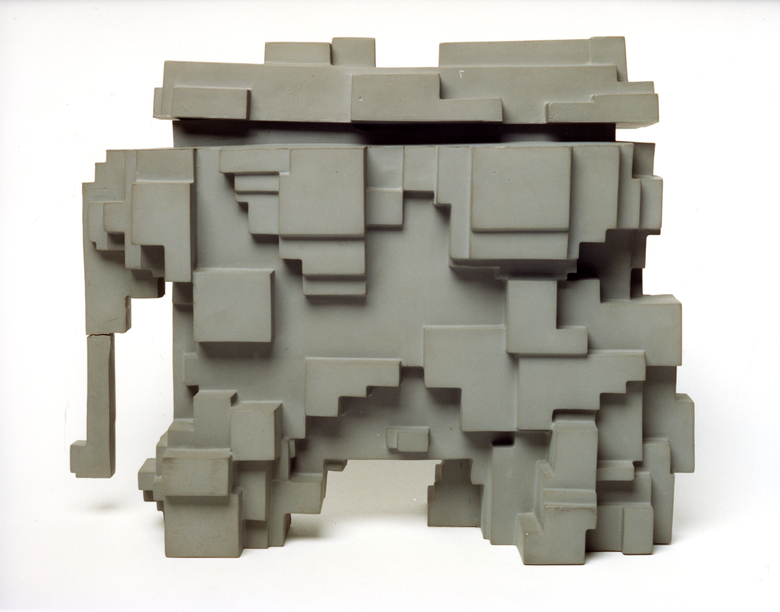

Image: Paolozzi elephant. FIFER:2022.0235

Remember those elephants I mentioned earlier? Well, following conservation they both went on display in Kirkcaldy Galleries, where you can see them until the beginning of March 2023. If you’d like to learn more about these peculiar pachyderms, check out our previous blog post here.

We also welcomed a piece of William Morris patterned linoleum into our collections. The sample was a gift from the William Morris Society Hammersmith, and is a piece of the only linoleum ever created from the Morris Company. It is believed to have been manufactured in Kirkcaldy in the 1870s. We haven’t had a chance to have this photographed yet, but are looking to have it on display in Kirkcaldy Galleries later in 2023.

January

In January I installed a new display in the Moments in Time gallery, this time featuring buildings associated with the linoleum industry which were demolished during the 20th century. I’ll be changing this display again in April – so watch this space!

What’s next?

2023 is going to be a very exciting year for the Flooring The World project. We’ll be working with communities in Newburgh and Falkland, as well as volunteers in Kirkcaldy, on some exciting projects which we’ll share later in the year. Plus we’ll be working on our exhibition, which will open at Kirkcaldy Galleries in November.

We’ll also be continuing to improve our collections, and to collect oral histories from those with first or second hand experience of the linoleum industry. If you have memories you’d like to share, please get in touch – no story is too small!

If you’re interested in being involved with the Flooring the World project, you can reach me by e-mailing lino@onfife.com, or by calling 07548777008. You can also keep up to date with the project by following the project page on Facebook, or by following Kirkcaldy Galleries and OnFife Museums on Instagram, Facebook or Twitter.

________________________________________________

Flooring the World is a two-year project exploring the history of the Fife linoleum industry. It is funded by the Esmée Fairbairn Collections Fun., which is run by the Museums Association.

![]()

As our Paolozzi elephants return to our museum stores, we take a closer look at these plastic pachyderms.

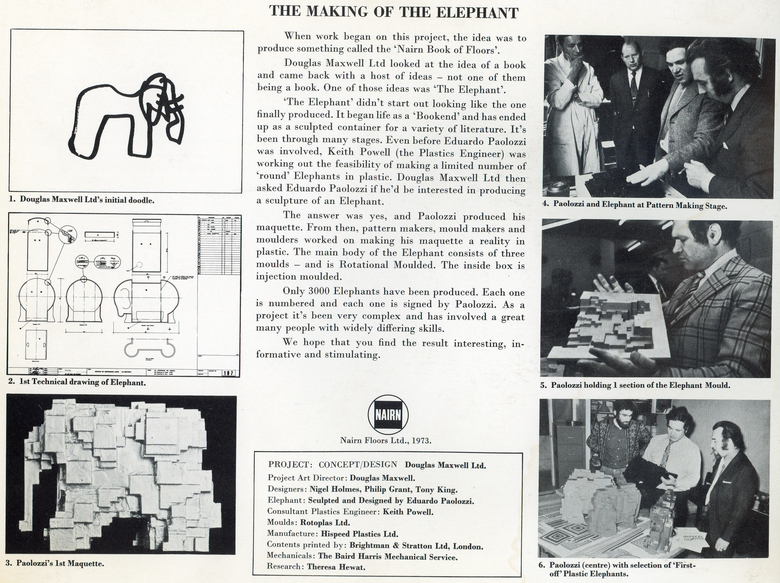

Picture the scene. Its 1970, and you’re a Scottish floorcovering manufacturer looking for a way to display brochures at tradeshows and in showrooms. It needs to be tidy, eye-catching, and chic enough to capture attention of potential customers. Obviously, the answer is to commission one of Scotland’s most influential artists to create you a series of 3000 elephant-shaped boxes.

Sounds like a leap, but that’s exactly what happened. At the time of the commission, Nairn Floors were in a strange position. They had survived the tumultuous decade of the 1960s, remaining a player in an industry that had changed dramatically. Between 1963 and 1970, a vast number of linoleum factories in Kirkcaldy had been demolished, and Nairn’s was now the only firm making floorcoverings in the town.

They had also diversified into vinyl floors, and would try their hand at carpet. As they began to diversify, they looked to consolidate their position by advertising their products to architects. These were coveted clients as, if they specified a certain brand or style of floorcovering for a large project, Nairn’s could guarantee bigger sales than they could secure with customers looking to floor individual homes. There was also the possibility that architects might come back time and time again, whereas domestic sales were – by the nature of linoleum’s long life-span – less likely to garner regular repeat purchases.

Initially, the company approached a design company called Douglas Maxwell Limited, with the idea to produce a volume called the ‘Nairn Book of Floors’. The company took the brief, and came back with several ideas – one of which was not a book at all, but an elephant. The idea was that the elephant would act as an attractive ‘bookcover’ but that the pages kept inside it could be updated as products changed.

Seems logical enough – but why an elephant? We’re a bit unclear on how that happened. Was it due to the elephantine pressure linoleum could withstand through a stiletto heel? Or perhaps the longevity of linoleums lifespan put some in mind of mammoth memories? The answer is most likely a mix of the two, supported by a universal truth: everyone likes elephants.

Each elephant was accompanied by a booklet explaining the design process, with Paolozzi’s signature unmissable on the front cover.

At the time, Eduardo Paolozzi was already a big name in the art world. Born in Leith in 1924, Paolozzi is considered by some to have provided a name to the era-defining Pop art movement, by including the word ‘Pop!’ in his 1947 collage If I Was A Rich Man’s Plaything. By 1972, he could boast one-man shows at MoMA, the Tate and the Scottish National Gallery (which now holds his full archive). Obviously, the next logical step was to make an elephant for Nairn’s. It seems a strange move, but of the project Paolozzi said:

“The object was exciting to me as a sculptor. In one sense, what could be more organic than an Elephant? (Or the idea of an Elephant?). To interpret this into completely non-organic shapes, practically all geometric elements, with an emphasis on the horizontal and vertical planes, was a fascinating problem. […] I was aware beforehand of the various technical processes the sculpture would have to undergo, but found that many of the craftsmen involved were using a technology of a very fine kind, and this opened an entirely new world to me.”

The elephants – while strange and unusual to us – were inspiring to Paolozzi. They introduced him to new techniques which he would later use in his own work – most notably the Cleish Castle Ceiling.

To create the elephants, he began by producing a maquette – or model – which ‘pattern makers, mould makers and moulders’ developed into a final design. Each elephant was accompanied by a booklet which detailed the process, in which it is modestly described as “very complex”.

3000 elephants were made and, though they occasionally pop up for sale in auction houses, today only a few are accounted for. There is one in the Metropolitan Museum in New York, one in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London – and two are held by us in our Collections Store at Bankhead, Glenrothes.

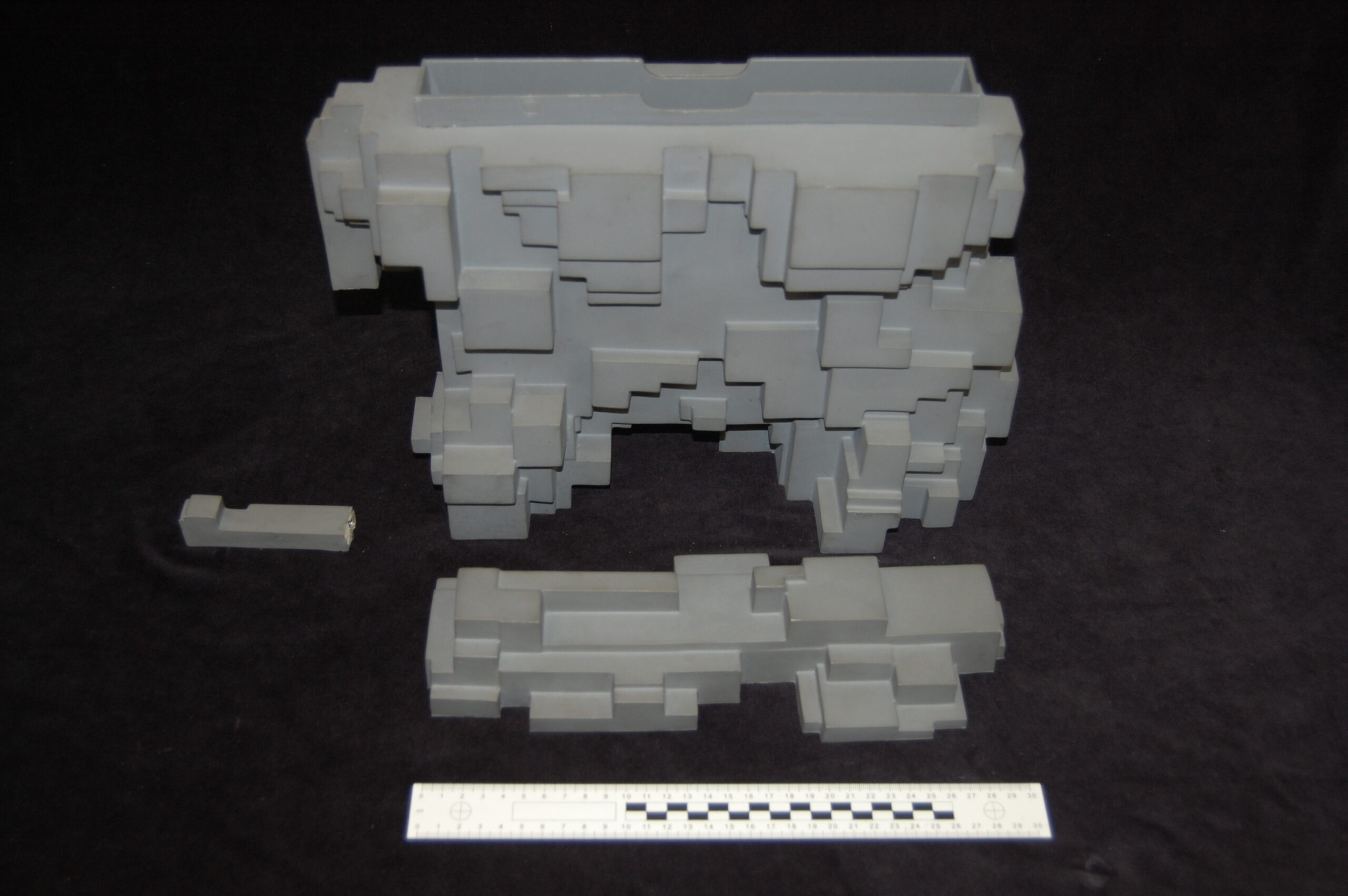

The first – marked number 768/3000 – had been with us for some time, and over the course of its life had lost its trunk. The second joined our collections this year. This one is not numbered, which may hint at it being a production proof outside of the run of 3000, perhaps produced especially for Nairn’s to keep – waiting in the archive until Nairn’s became Forbo, and Forbo chose to donate their archive to OnFife. This one had fared slightly better, but still had a few cracks across its surface.

Number 768, before conservation. KIRMG:1986.0300

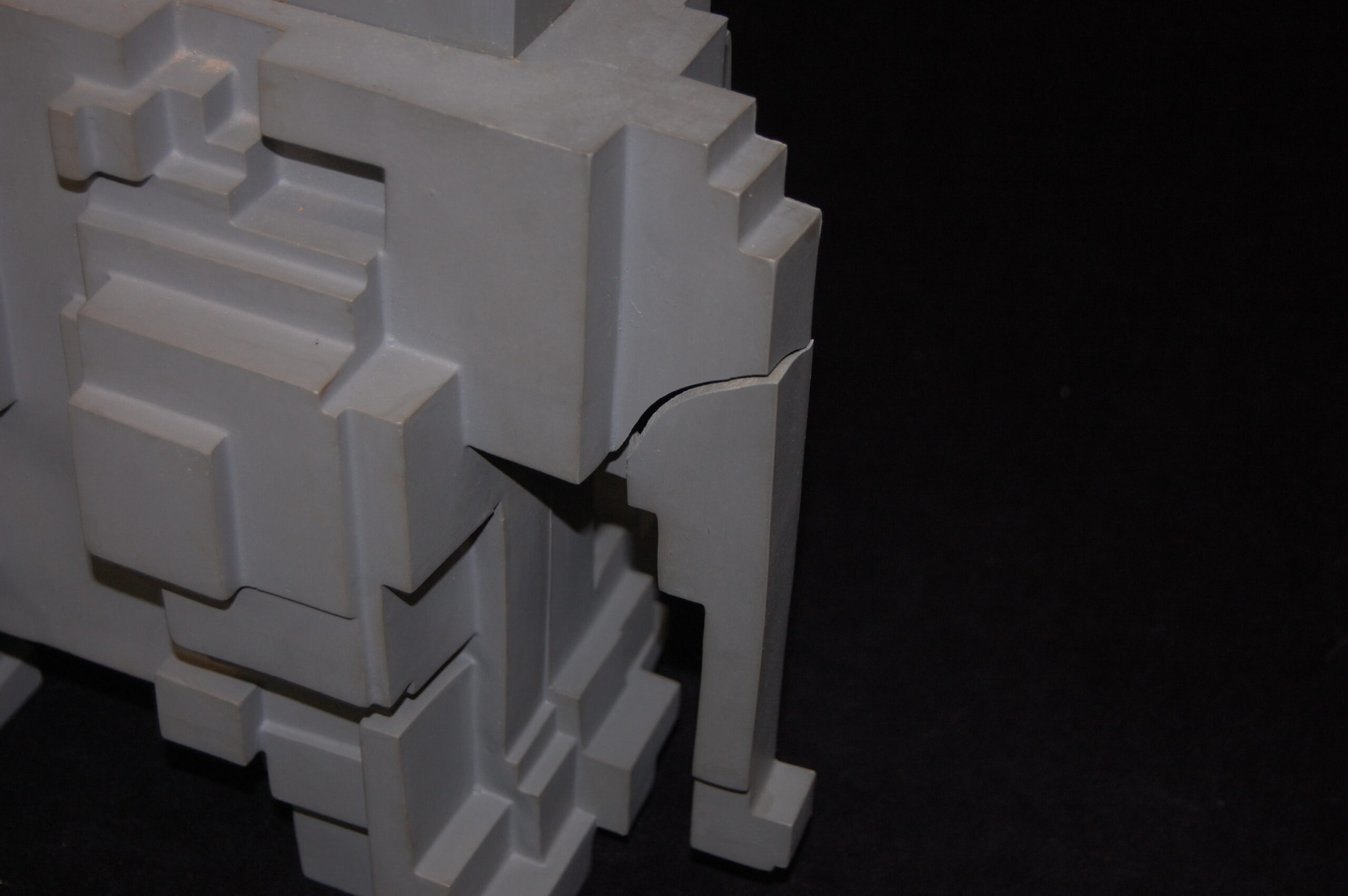

While we’re all aware of the devastating environmental impact of plastic, many people are not aware of how difficult it is to preserve and care for. As it ages – which can be exacerbated by light or heat – plastic begins to deteriorate. This deterioration manifests in different ways, depending on the type of plastic; some become brittle and crack, some flake apart, some appear to melt, and most of these processes produce gasses which can damage other objects around them. On top of this, it is very difficult to tell the hundreds of different types of plastics apart. This makes care and preservation even more difficult; if we do not know what we are dealing with, we cannot tailor our behaviour to best suit its needs.

The unnumbered elephant from the Forbo Archive, with a few cracks across its surface. FIFER:2022.0235

This proved to be an issue when it came to the elephants. It was impossible to identify which kind of plastic they were made out of and, as such, the conservator could not predict how they might behave in future. Ultimately, this led to us deciding to only conserve one of them – 768. While this elephant’s trunk could be repaired using a dowel, the cracks on our unnumbered elephant would require adhesive, which could cause further damage in future if the plastic were to expand or contract. To protect both as much as possible, we opted for different treatments. Together, the pair make a perfect ‘before’ and ‘after’.

Number 768 after conservation, re-trunked and ready to go!

Our original elephant wasn’t included in the Queer-Like Smell exhibition in 1992, so the pair have yet to make their debut appearance at one of our venues. Until now! You can find the elephants at Kirkcaldy Galleries from 16 December 2022 – 8 March 2023.

Flooring the World is a two-year project exploring the history of the Fife linoleum industry. It is funded by the Esmée Fairbairn Collections Fund, which is run by the Museums Association.

As part of the Flooring the World project, we are looking to actively improve our linoleum collections. This means rehousing the objects we already have, conserving those which need a bit of TLC, and researching those we know less about. It also means welcoming new objects into the collection and, to celebrate Scottish Archaeology Month, we wanted to tell you all about a recent addition.

Resin. FIFER.2022.0639

This lumpy orange stone was found on a beach on the shores of the Firth of Forth by a schoolboy in the 1970s, who initially thought it was a piece of amber. It was sent to the National Museum of Scotland, who told them that – instead – it was actually a large piece of resin.

Now, this is where the archaeology comes in. A lot of us, when we think of archaeology, imagine trenches dug in fields or roads, with lots of hat-wearing, hard-working people toiling through the mud to find Roman coins, Celtic bones, or – more usually, as several archaeologists have told me – more mud, and maybe the odd chicken bone.

In fact, this is just one type of archaeology. But, archaeological material can be discovered in lots of different ways. Artefacts can also be revealed by chance; washed up on beaches and river-banks, or exposed by storms of flooding damaging the landscape.

When we find something in this way, the challenge is then to work out how it came to be where it is. Did it enter the water way, and then get moved by currents to where you found it? Or was it buried (by accident or on purpose) and then exposed by erosion? And, then, a second question: how old is it? Has it been making its way to the beach for centuries, millennia, or just days?

These questions are more difficult to answer on the tideline than on dry land. If an object or site has been exposed by extreme weather, archaeologists may only have a short amount of time to carry out their investigations before the area is further damaged or completely destroyed. Finds will have to be quickly catalogued and removed, as any clues left unnoticed will be washed away. This was the case with the Lundin Links burial ground, which was exposed by storms shortly before our resin was found (which you can learn more about here).

Alternatively, if an object is washed up on a shoreline then we have no clues from its surroundings to tell us more about it. When removing something from the ground the depth at which is it buried, what is above and below it, and where it is all tell us something about it. This is called its archaeological ‘context’. If we don’t have this, we have to get more creative, and look at the object itself.

So, to start with, what is resin? Resins are viscous liquids which are secreted by plants when they are damaged to protect them from pests and disease. The thing that we call ‘amber’ – which the schoolboy who found our resin thought they had stumbled across – is prehistoric resin which has become fossilised and turned into stone. It starts life as resin and – as Jurassic Park taught us all – ends up decorating the canes of eccentric millionaires who use the mosquitos trapped within to unravel the genetic codes of extinct megafauna.

But, if that doesn’t happen, resin can be a useful raw material in a number of different industries. If you’ve ever played a violin, viola or cello, you’ll have used a resin to prepare your bow. If you’ve ever been second in line to offer a gift to Jesus Christ, you’ll have opted for a resin known as frankincense. And, if you’ve ever made linoleum, you’ll have used resin to create the thick, waterproof substance which makes up the surface of the Fife’s favourite floorcovering.

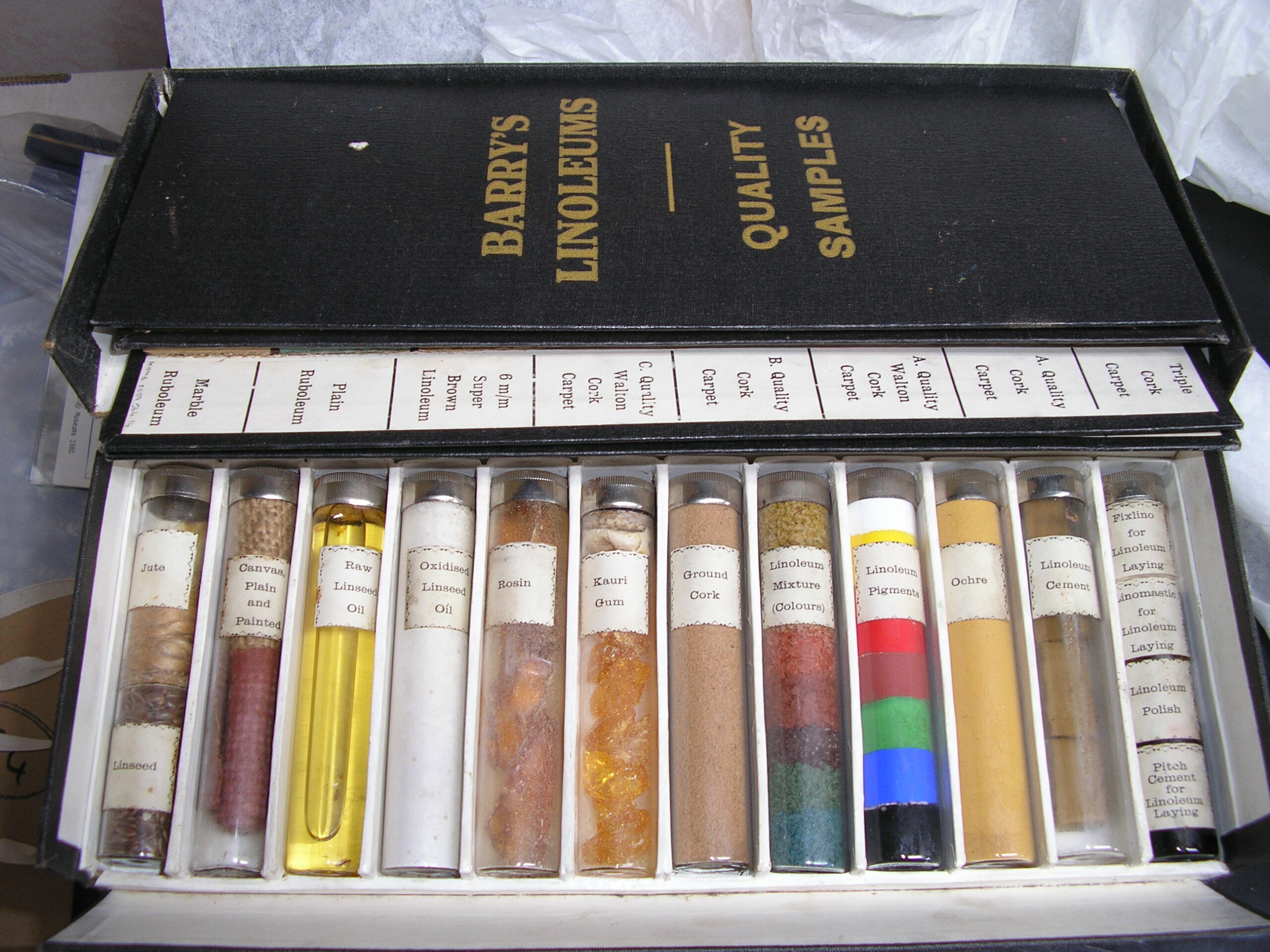

This sample case contains different materials used to make linoleum, including resin, fifth from the left. KIRMG.2007.564.1-17

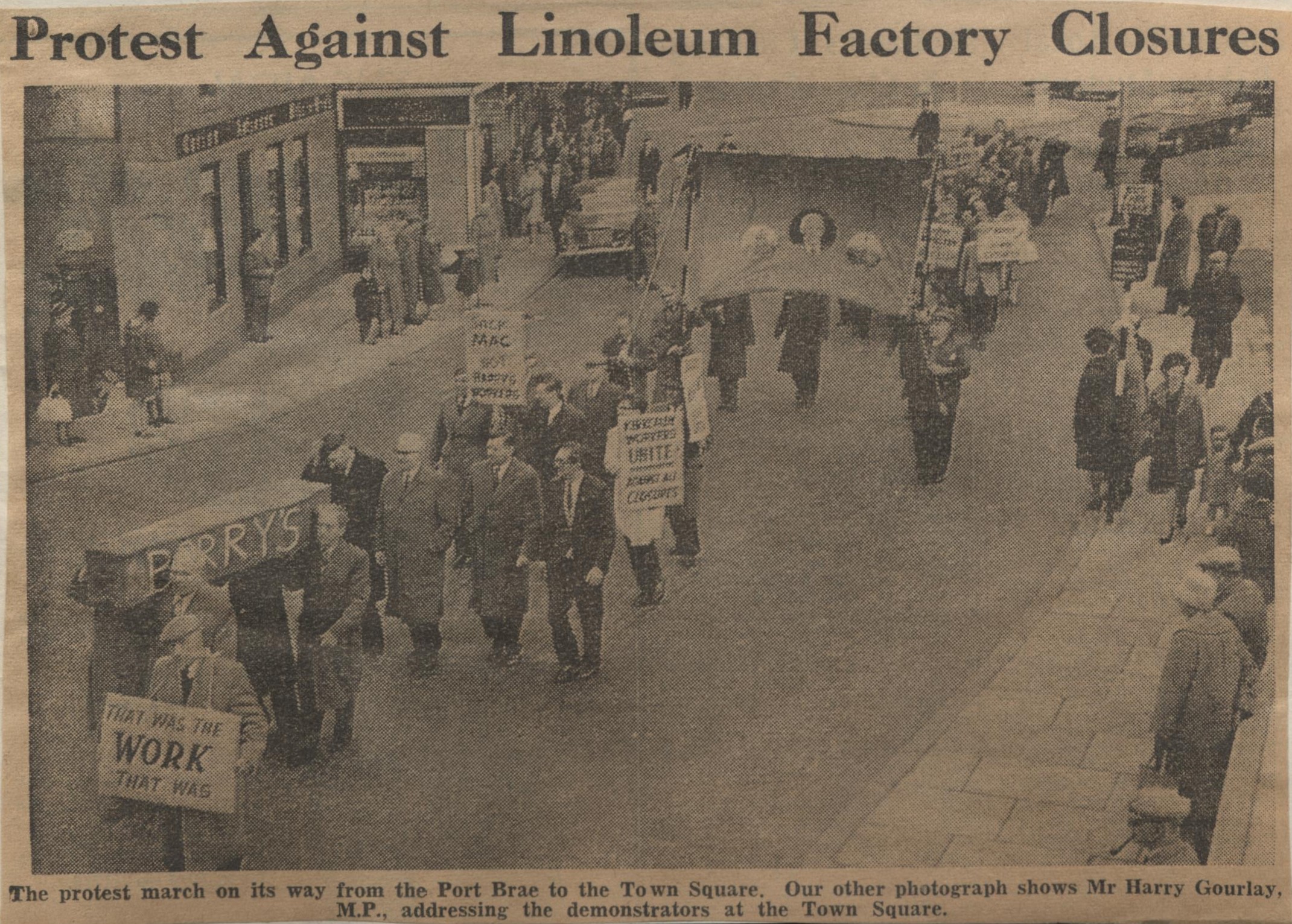

This, we think, is how our piece of resin ended up Forthside. During the 1960s, the Fife linoleum industry suffered several losses. Perhaps most significant was the decision of Barry, Ostlere and Shepherd – Kirkcaldy’s second oldest and second largest linoleum manufacturer – to cease all production of the floorcovering in the town, relocating production to Staines, Middlesex.

This change had an enormous impact on the shape of Kirkcaldy. Up until the end of the 1960s, the town had been dominated by linoleum factories – generating the ‘queer-like smell’ which they town became famous for. In particular, the area around Kirkcaldy galleries was filled with Barry’s buildings.

Newspaper cutting from the Local Studies collection at Kirkcaldy Galleries.

Between 1969 and 1970, all of these buildings were demolished. In addition, several buildings belonging to Nairn’s linoleum firm – including the original ‘Nairn’s Folly’ floorcloth factory – were also destroyed. The rubble and waste material generated by the demolition was deposited at Pathhead, to ‘build up the beach’. With so much linoleum related material so near to the beach, we suspect that this may have been when our resin entered the river Forth, turning up on the shoreline not long afterwards.

You can see this object – and learn more about the linoleum industry in the 1960s – in a temporary display in the Moments In Time Gallery, Kirkcaldy Galleries until 27 October 2022. You can also check out our blog post about the display here.

_________

This blog was written by Lily Barnes, curator working on the linoleum project Flooring the World (2022-2024). Flooring the World is a two-year project exploring the history of the Fife linoleum industry. It is funded by the Esmée Fairbairn Collections Fund, which is run by the Museums Association, funding projects that develop collections to achieve social impact.

A restored prehistoric pot, currently on display in Kirkcaldy Galleries, was discovered when a human skeleton was dramatically exposed by builders behind Kirkcaldy High Street in 1980 in what is now a car park. It is the focus of new research uncovering untold stories of the find and celebrating Kirkcaldy’s Bronze Age heritage.

A dig was carried out in Kirkcaldy in 1980. Image: TEMP:2012.4175

Found in large broken pieces, the fired clay pot was first rebuilt in 1980 by archaeologists at The University of Glasgow who undertook the rescue excavation. It has now been fully restored by a conservator thanks to the generosity of the Friends of Kirkcaldy Galleries.

Pot sherds as they were first found. Image: TEMP:2012.4183

The vessel after it was rebuilt by archaeologists at The University of Glasgow in 1980. Image: KIRMG:1981.1819

Vessel, after being conserved at the Scottish Conservation Studio in 2022.

Initially when first discovered the burials was widely reported in the press as being associated with a type of Earlier Bronze Age pottery known as a Beaker. In fact, it belongs to a different contemporary ceramic tradition and the pot is a Food Vessel. Of European origin, Beakers were established here a few centuries before the appearance of Food Vessels, and while the two overlap in time, they are recognized as distinct ceramics associated with apparently different practices. The relationship between these different ceramics and their users continues to be the focus of much archaeological debate. Radiocarbon dating and new analytical techniques such as isotopic analysis are adding intriguing evidence about the lives, health and mobility of the prehistoric people buried with such pots.

As a specialist in this type of pottery, I undertook a detailed examination of the Kirkcaldy High Street vessel ahead of its recent conservation and reconstruction. Found across Scotland, Food Vessels date from 2560-1450 BCE. These pots often accompany both inhumation and cremation burials in purpose-built cists – distinctive rectangular stone constructions – with the deceased. Historically assumed to have served as containers for food for the afterlife or the funeral feast (hence their name), current studies suggest that some of these pots were previously used in domestic settings for the cooking or storage of dairy products.

In terms of appearance, individual pots come in a variety of shapes and sizes. Hand-made each is similar but different, often sharing decorative elements found on other vessels. Most stand 10-25 centimeters tall with flat bases and impressed or incised linear decoration. Around 80% of the original pot survives, it is 16.5 cm high with a rim diameter of 16 cm with traces of coil construction.

The shape of the Kirkcaldy High Street Food Vessel is commonly found throughout Scotland. It has two prominent ridges and an intermediate groove on the shoulder, and a slightly rounded tapering lower body. It is decorated with comb impressions and a common herringbone design around the neck. Similar decorated vessels have been found on other sites in Fife, as well as in most other areas of Scotland. Such common features reveal creative connections among well-connected bronze age communities. The potters were drawing on a shared knowledge of decorative motifs and techniques.

Visual similarities between Beakers and Food Vessels can be seen. These ‘drinking vessels’, while displaying a different range of forms, often feature very similar styles of decoration to those found on Food Vessels. Similarly, Beakers mainly survive in cists but are found more commonly with individual adult burials where the body is lying in a crouched position on one side.

A total of three cist graves were uncovered during the Kirkcaldy High Street 1980 excavations. But only one had a Food Vessel. Human remains were also present in one of the other previously disturbed burial cists. Specialist analysis will soon reveal further insights into the people buried in this small cemetery on an earlier sandy raised beach back in the Bronze Age.

The new research is part of an ongoing project at The University of Glasgow to address unpublished archaeological excavation archives. The original excavator died before completing the original analysis. There is much to uncover from digging through older discoveries in museum stores. Working in partnership with OnFife Collections Curator Jane Freel the project includes events to share the results and celebrate the discovery and the prehistoric past with the local community.

Keen to find out more?

- Visit our window display at Kerry Photography, 243 High Street, the site of the original burial (on display until the end of September).

Window display at 243 High Street, Kirkcaldy

_________

This blog was written by Dr Marta Innes – Archaeologist, Freelance British Prehistoric Pottery Specialist and Illustrator

The 1960s was a decade of immense change for Kirkcaldy. Change – and not just the smell of linseed oil – was in the air. Linoleum manufacturers were innovating, creating new products and fashionable designs for new and exciting times.

However, the decade also saw the beginnings of sharp decline of linoleum production in Britain. The future of the Fife industry – and the thousands of people who depended on it for work – began to look increasingly bleak.

We’ve just installed a new temporary display in our Moments In Time gallery (on display until 27 October 2022), exploring some of these changes using objects and photographs from our collections.

While creating the display, we’ve been thinking about what it would have been like to live in Kirkcaldy during this uncertain time. As the fortunes of the linoleum industry began to shift, what did people feel, what did they see – and what music did they listen to?

Why music? Have you ever been going about your life, and heard a song – in a shop, on the TV, on the radio – and been instantly transported to another time when you heard, sang or danced to that song? Last week I was in a pub where a Red Hot Chili Peppers song was playing, and immediately remembered driving in the car with my dad, singing to the same song and holding my hand out of the open window. Something like this has probably happened to you too.

With music from times and places which we didn’t experience, music can have a slightly different effect. It’s easy to forget that people in the past – whether it’s the 1960s or the 1560s – were essentially the same as we are now. They had the same thoughts, feelings, likes and dislikes. Listening to music from those times, regardless of whether we know the songs, help us to remember that, and to better understand our history.

Newspaper cutting from the Local Studies collection at Kirkcaldy Galleries.

So, we created this playlist as a bit of an experiment: to help those of you who were in Kirkcaldy during the 1960s remember the time more clearly, and to help those of us who weren’t to imagine what it might have been like. If you have a Spotify account, you can listen here. If not, click here to listen on Youtube. Without further ado, here it is:

1. (If I Say I Love You) Do You Mind? – Anthony Newley

2. Walking Back to Happiness – Helen Schapiro

3. Moon River – Danny Williams

The first three songs on the playlist were all hits in the UK between January 1960 and December 1961 – we picked them to correspond to the three samples of linoleum in the display. These songs don’t mirror the psychedelic influences in the linoleum designs, but they do represent a world on the cusp of a huge change. The new genres and styles of music which would become popular in the next few years – namely rock and roll – would come to dominate more traditional pop music.

4. Lovesick Blues – Frank Ifield

But, before we embrace change wholeheartedly, let’s indulge in a little yodelling. This song – made famous by Hank Williams in 1952 (and then again by Mason Ramsey AKA ‘the yodelling kid’ in 2018) was a hit in 1962, when customers from Kirkcaldy to Kings Lynn were covering their floors with designs from this pattern book. While it’s still a quite traditional ditty, we liked the imagining happy lino owners square dancing on their newly laid kitchen floors (and thought you might like to imagine it too).

This song was playing across the UK in 1963, and was at its most popular at the time the news of the Barry’s redundancies was announced in the Fife Free Press in April. It’s a very upbeat tune, and we were sort of hoping for something more in-keeping with the sadness many people in Kirkcaldy would have felt. Ultimately though, we decided to keep it in – it’s important to remember that the rest of the world doesn’t automatically follow suit during dark times.

6. From Me To You – The Beatles

Finally, the Beatles. This playlist would have been empty without them, as the band have quite a few connections to Kirkcaldy, and to our linoleum collection. This song would have been heard across Kirkcaldy the day of the Barry’s march in May 1963, and the band would play a show at the Carlton Cinema on Park Road just months later.

7. She’s Not You – Elvis Presley

Though we tended towards British artists when making our selections, we’d have been remiss if we didn’t include a bit of Elvis. As one of the most iconic voices of the decade, we were sure that people in Kirkcaldy must have been singing this song as events unfolded. This song was a hit when Nairn’s announced that they would be merging with rival firm Williamson’s in September 1962, a move which was finalised in the winter of 1963.

Like other Kirkcaldy firms, Nairn’s was forced to downsize, diversify and consolidate its business during the 1960s. The decision to merge with Williamson’s, however, may have been what saved it from a full closure; unlike Barry’s, its Kirkcaldy production survived the decade.

Newspaper cutting from the Local Studies collection at Kirkcaldy Galleries.

8. Where Do You Go To – Peter Sarstedt

From 1969, linoleum factories began to disappear from Kirkcaldy en-masse. The Barry’s factory complex, which had been mainly concentrated around the train station – was demolished in 1969. This completely changed the shape of the town; the queer like smell that had announced the town to visitors arriving on the rails for a hundred years was beginning to fade as the buildings were levelled. The area today is unrecognisable.

Not long after, the Nairn’s Pathhead complex suffered the same fate. This included the original ‘Nairn’s Folly’ building – a relic of the beginning of the floorcovering industry in Kirkcaldy. For residents of the town, this must have seemed a particularly bad omen.

This song was a hit earlier in the year, but we felt its melancholy, nostalgic tone seemed to fit well with the way the demolition of the Kirkcaldy linoleum factories made us feel – and perhaps made those in the town at the time feel, too.

This the first time we’ve used music to supplement our displays, and we’d love to know what you think. If this has prompted any thoughts or memories, or if you have any feedback you would like to share, you can e-mail Lily (Flooring The World Engagement Curator) at lino@onfife.com

_________

This blog was written by Lily Barnes, curator working on the linoleum project Flooring the World (2022-2024). Flooring the World is a two-year project exploring the history of the Fife linoleum industry. It is funded by the Esmée Fairbairn Collections Fund, which is run by the Museums Association, funding projects that develop collections to achieve social impact.