In the autumn of 1939, workers at Nairn’s floorcovering factories downed tools and marched through the streets of Kirkcaldy. Over the summer of 2023, Fraser Scott – a volunteer with the Flooring the World project – researched the strike, and its context in relation to labour rights in Scotland in the early 20th century.

The Nairn family was generally seen and thought of themselves as being “philanthropic” towards their employees. The firm had been involved in community projects since the late 19th century. In 1877, they funded of the construction of St Brycedale church, and in 1894 Michael Barker Nairn funded the renovation and rebuilding of Kirkcaldy Burgh School. He also “established trust funds” for medals, prizes and university bursaries to further support the school’s pupils.

A view of Kirk Wynd. The steeple of St Brycedale Church is visible to the right.

In their factories, Nairn’s extended this generosity to their employees. They organised events events – such as summer excursions to the family estate at Rankeilour, Cupar – and amenities such as cinemas, sports facilities. When it came to wages, Nairn’s employees were given a yearly bonus and, most notably, during WWI the company provided payments to the families of the six hundred workers who had joined the armed services.

However, this philanthropy doesn’t hide the underlying labour tensions between Nairn’s and their employees. In an oral history interview in OnFife’s collections David Lawson, who was employed at Nairn’s in 1939, points to the general hostility that Nairn’s had towards unions and dissenting workers. Describing an occasion when he and other union members met with Nairn’s officials, he remembered: “[They said] you men, you should realise we have done a lot for Kirkcaldy”. The implication to Lawson, was that the philanthropy of both firm and family was seen as a moral excuse to justify intimidating their workers into not organising.

Along with this, Lawson noted that the company were quick to hand out penalties. The yearly bonus would be withdrawn “automatically” if a worker was late. The same applied for striking. Lawson notes that he was among a group of workers fired en masse for organising:

“I missed the first fifty, the next week another fifty fired and my name was on the list”.

This indicates that, even before the 1939 strike, Nairn’s attitudes towards unions and strike action was generally hostile and draconian. To some, this indicated that their philanthropic policies had a dual purpose: to discredit the unions by showing that Nairn’s had a concern for their workforce, and to discourage the workers themselves from organising against them.

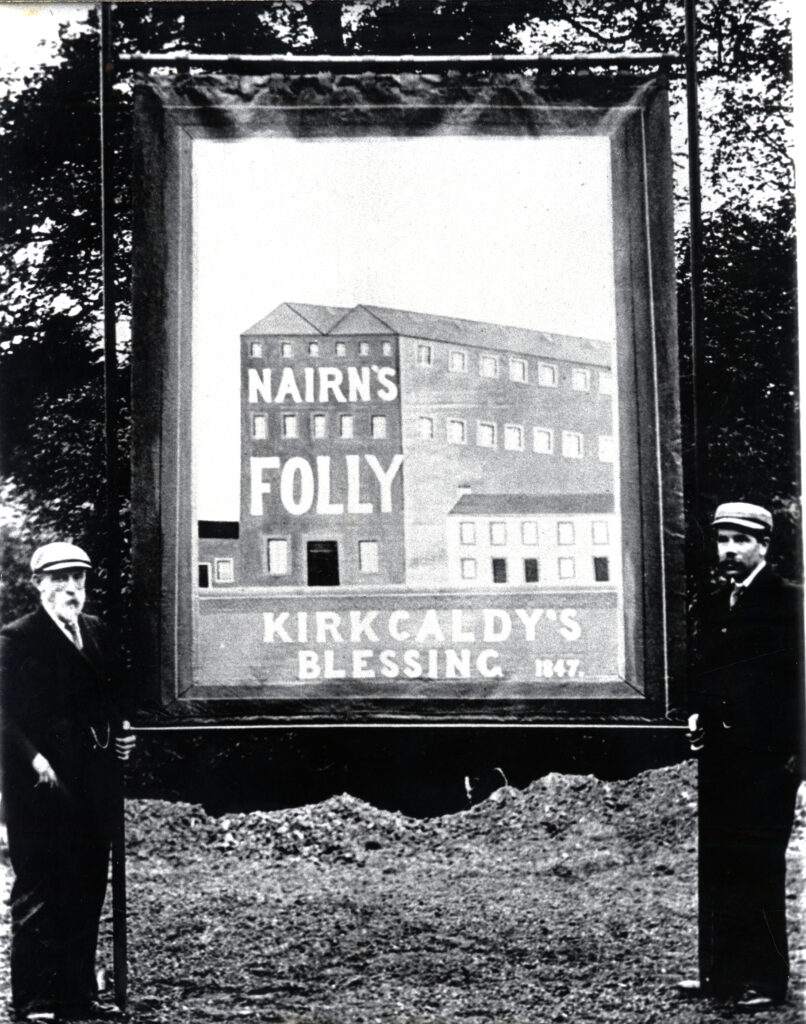

In promoting their charitable works, Nairn’s presented themselves as ‘Kirkcaldy’s Blessing’. This floorcloth banner was carried by workers in their annual processions c.1900 – 1909.

Striking in Scotland

The Nairn’s strike can be seen in the context of other examples of industrial action in Scotland. During the early 20th century there were several upheavals in labour relations at the time, most notably ‘Red Clydeside’ and the General Strike.

Red Clydeside occurred in the immediate aftermath of WWI. Already rising tensions over poor pay and high rent in Glasgow (the cause of the 1915 rent strikes) mixed with the lack of opportunities for returning soldiers gave ample opportunities for union activists to organise and agitate. As such in January 1919 the CWC (Clydeside Workers Committee) organised a mass demonstration in George Square involving up to 25,000 with inevitable clashes resulting in 36 injuries.

The Red Clydeside events of 1919 were important in the Scottish context, as labour organisers would rise to national prominence and even be elected to office. Organiser Willie Gallacher was later elected as an MP for West Fife. Socialist organisations were also propelled by Red Clydeside. The Labour party, having demonstrated their solidarity with workers, secured massive gains in Glasgow and other industrial areas in Scotland

Following this, the 1926 General Strike also provided a precedent for industrial action across the UK. The strike was largely caused by the changing prospects of the British coal mining industry. During WWI, overseas sources of coal from Germany and France had been cut off. This meant that increasing demand was placed on mines in the British Isles, with workers wages rising alongside it. The end of the war meant that this period of prosperity for coal miners came to an end. Already working long hours in dangerous and dirty conditions, miners were now faced with a dramatic drop (almost half, in some cases) in their pay/

This – coupled with significant inflation which impacted workers and businesses across the country – led the Trade Unions Congress (TUC) to call for a general strike of all workers. From the 4th May, at least 1.5 million workers ‘from Land’s End to John O’ Groats’ refused to work.

Despite the impressive turn out, in terms of gains for the British labour movement and trade unions the strike was a disaster. In response, the British government amended the 1906 trade relations act to stop unions from striking together and to prevent mass picketing outside workplaces.

The Nairn’s Strike

The strikers passing Nairn’s head offices at Braehead House, Victoria Road.

By October 1939 the National Union of General and Municipal Workers (NUTW), had made several applications for official recognition from Nairn’s. The firm rejected these, claiming that workers were being “harassed” by union members. As evidence, they referred to workers who had complained about being approached by union representatives during work hours. In one example, a worker named George Anderson was said to have approached packer Ethel Stevenson “with a view to having her join the union”. Stevenson “had the impression that [Anderson] was forcing her do so.

In response to Nairn’s refusal, Kirkcaldy NUTW secretary John Kay insisted that the union to “not back down”. They agreed to take action, initially planning a sit-in at the factory beginning on the 9 October. However, in the preceding days Nairn’s fired seven workers in an attempt to intimidate would-be strikers. As such, the NUTW instead decided to march through the centre of Kirkcaldy.

This move was carefully calculated. On the one hand, it was a more deliberate – and public – show of strength than the planned sit in. Hundreds of residents across Kirkcaldy would see the strikers, causing reputational damage to the town’s beloved Nairn’s. On the other, marching through the town allowed workers to demonstrate against their employers legally; if they moved throughout the town, they would pass close by their workplaces, but not picket directly outside them.

The resulting march involved between 1500 to 2000 workers – about 90 percent of all Nairn factory employees. The strikers began near the floorcloth factory in Pathhead, before turning down Victoria Road. This lead them past the linoleum works, and the company’s head office at Braehead House. They then continued past what is now Kirkcaldy Galleries, and on to the Adam Smith Theatre.

The strikers outside the Adam Smith Theatre.

On the following day the strike had intensified, with the Motorman’s union joining with the NUTW. The Motorman refused to supply the linoleum industrial with oil, meaning that the workers who remained were unable to operate their machines. Production ground to a halt.

Such a work stoppage forced Nairn to enter into negotiations. In the interim, employees would return to work with the promise that they would not be “victimis[ed]” for striking. Between the 17th and 18th both sides laid out their demands. Nairn’s wanting to stop union activism from occurring, and to maintain control over assigning work. The NUTW wanted their union to be officially recognised and to guarantee scheduled meetings between representatives and the firm. On the 19th October, the Unions won out. Nairn’s agreed to recognise the NUTW, on condition that they did not promote union activity during work hours and that Nairn would be able to take in workers complaints and keep control of business management.

If you would like to learn more about the Fife linoleum industry, you can visit the Flooring the World exhibition at Kirkcaldy Galleries (15 November 2023 – 25 February 2024). Flooring the World is a two-year project exploring the history of the Fife linoleum industry. It is funded by the Esmée Fairbairn Collections Fund, which is run by the Museums Association.