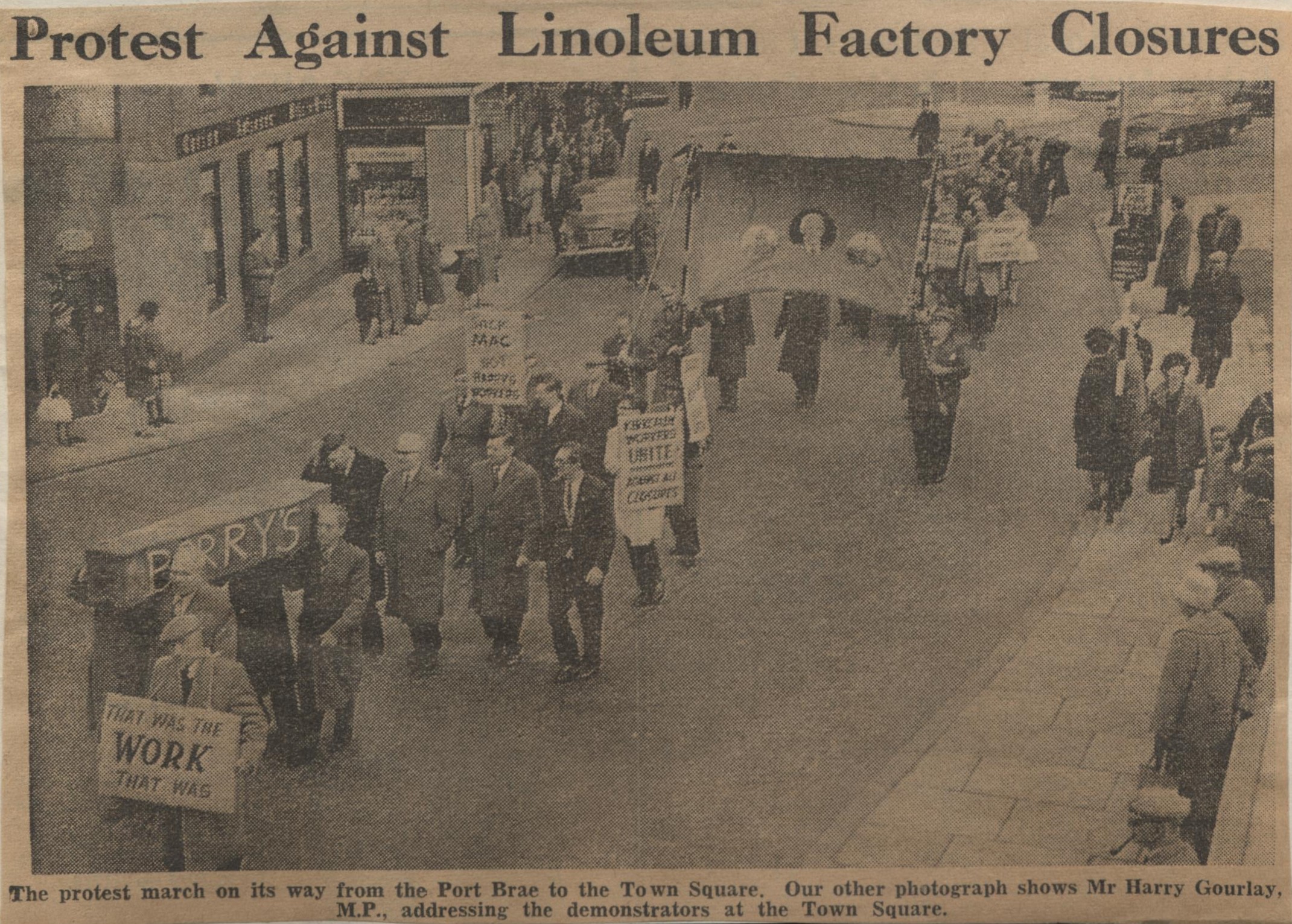

In the autumn of 1939, workers at Nairn’s floorcovering factories downed tools and marched through the streets of Kirkcaldy. Over the summer of 2023, Fraser Scott – a volunteer with the Flooring the World project – researched the strike, and its context in relation to labour rights in Scotland in the early 20th century.

The Nairn family was generally seen and thought of themselves as being “philanthropic” towards their employees. The firm had been involved in community projects since the late 19th century. In 1877, they funded of the construction of St Brycedale church, and in 1894 Michael Barker Nairn funded the renovation and rebuilding of Kirkcaldy Burgh School. He also “established trust funds” for medals, prizes and university bursaries to further support the school’s pupils.

A view of Kirk Wynd. The steeple of St Brycedale Church is visible to the right.

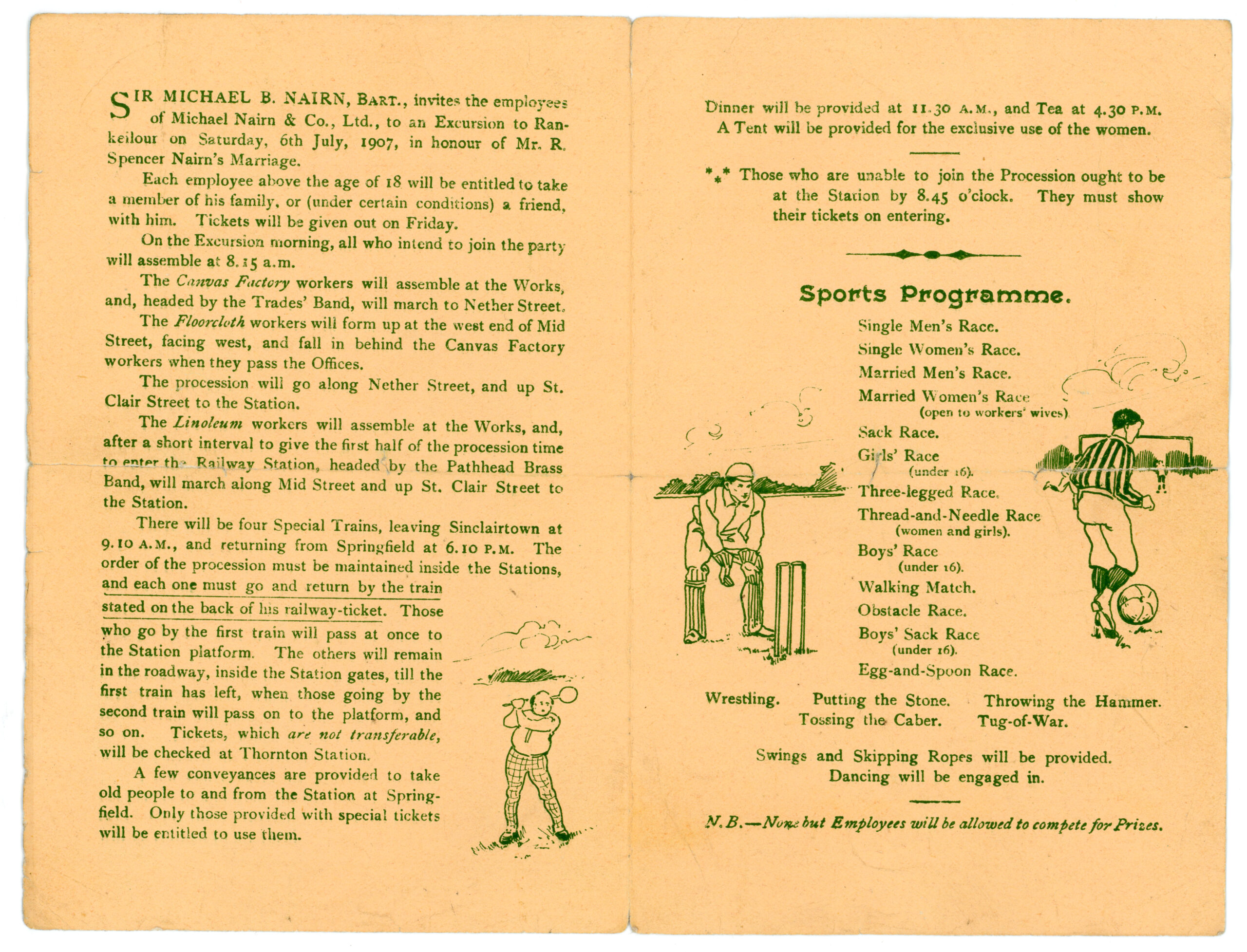

In their factories, Nairn’s extended this generosity to their employees. They organised events events – such as summer excursions to the family estate at Rankeilour, Cupar – and amenities such as cinemas, sports facilities. When it came to wages, Nairn’s employees were given a yearly bonus and, most notably, during WWI the company provided payments to the families of the six hundred workers who had joined the armed services.

However, this philanthropy doesn’t hide the underlying labour tensions between Nairn’s and their employees. In an oral history interview in OnFife’s collections David Lawson, who was employed at Nairn’s in 1939, points to the general hostility that Nairn’s had towards unions and dissenting workers. Describing an occasion when he and other union members met with Nairn’s officials, he remembered: “[They said] you men, you should realise we have done a lot for Kirkcaldy”. The implication to Lawson, was that the philanthropy of both firm and family was seen as a moral excuse to justify intimidating their workers into not organising.

Along with this, Lawson noted that the company were quick to hand out penalties. The yearly bonus would be withdrawn “automatically” if a worker was late. The same applied for striking. Lawson notes that he was among a group of workers fired en masse for organising:

“I missed the first fifty, the next week another fifty fired and my name was on the list”.

This indicates that, even before the 1939 strike, Nairn’s attitudes towards unions and strike action was generally hostile and draconian. To some, this indicated that their philanthropic policies had a dual purpose: to discredit the unions by showing that Nairn’s had a concern for their workforce, and to discourage the workers themselves from organising against them.

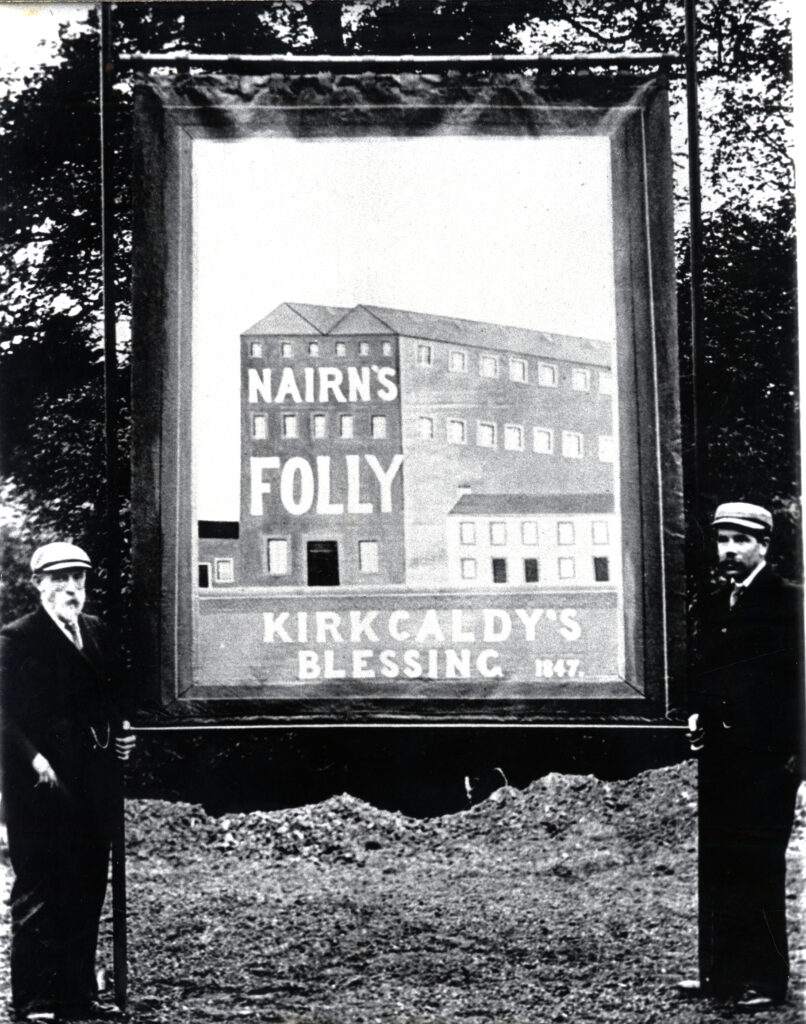

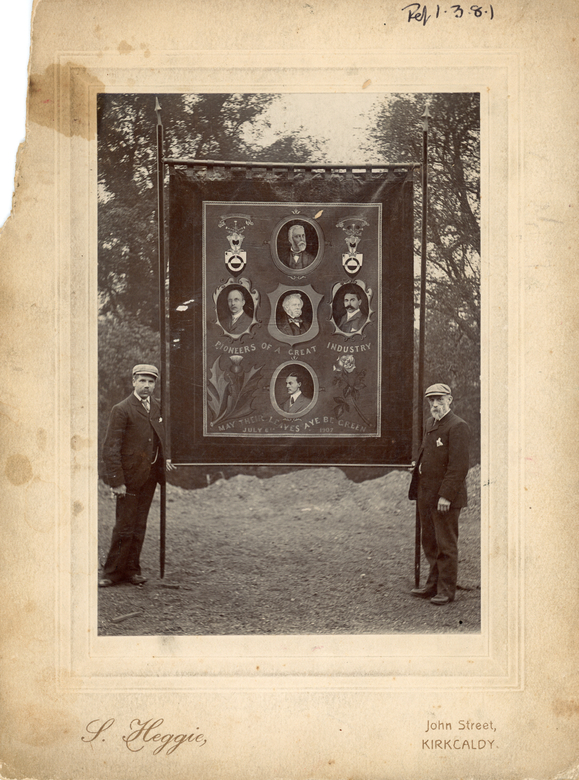

In promoting their charitable works, Nairn’s presented themselves as ‘Kirkcaldy’s Blessing’. This floorcloth banner was carried by workers in their annual processions c.1900 – 1909.

Striking in Scotland

The Nairn’s strike can be seen in the context of other examples of industrial action in Scotland. During the early 20th century there were several upheavals in labour relations at the time, most notably ‘Red Clydeside’ and the General Strike.

Red Clydeside occurred in the immediate aftermath of WWI. Already rising tensions over poor pay and high rent in Glasgow (the cause of the 1915 rent strikes) mixed with the lack of opportunities for returning soldiers gave ample opportunities for union activists to organise and agitate. As such in January 1919 the CWC (Clydeside Workers Committee) organised a mass demonstration in George Square involving up to 25,000 with inevitable clashes resulting in 36 injuries.

The Red Clydeside events of 1919 were important in the Scottish context, as labour organisers would rise to national prominence and even be elected to office. Organiser Willie Gallacher was later elected as an MP for West Fife. Socialist organisations were also propelled by Red Clydeside. The Labour party, having demonstrated their solidarity with workers, secured massive gains in Glasgow and other industrial areas in Scotland

Following this, the 1926 General Strike also provided a precedent for industrial action across the UK. The strike was largely caused by the changing prospects of the British coal mining industry. During WWI, overseas sources of coal from Germany and France had been cut off. This meant that increasing demand was placed on mines in the British Isles, with workers wages rising alongside it. The end of the war meant that this period of prosperity for coal miners came to an end. Already working long hours in dangerous and dirty conditions, miners were now faced with a dramatic drop (almost half, in some cases) in their pay/

This – coupled with significant inflation which impacted workers and businesses across the country – led the Trade Unions Congress (TUC) to call for a general strike of all workers. From the 4th May, at least 1.5 million workers ‘from Land’s End to John O’ Groats’ refused to work.

Despite the impressive turn out, in terms of gains for the British labour movement and trade unions the strike was a disaster. In response, the British government amended the 1906 trade relations act to stop unions from striking together and to prevent mass picketing outside workplaces.

The Nairn’s Strike

The strikers passing Nairn’s head offices at Braehead House, Victoria Road.

By October 1939 the National Union of General and Municipal Workers (NUTW), had made several applications for official recognition from Nairn’s. The firm rejected these, claiming that workers were being “harassed” by union members. As evidence, they referred to workers who had complained about being approached by union representatives during work hours. In one example, a worker named George Anderson was said to have approached packer Ethel Stevenson “with a view to having her join the union”. Stevenson “had the impression that [Anderson] was forcing her do so.

In response to Nairn’s refusal, Kirkcaldy NUTW secretary John Kay insisted that the union to “not back down”. They agreed to take action, initially planning a sit-in at the factory beginning on the 9 October. However, in the preceding days Nairn’s fired seven workers in an attempt to intimidate would-be strikers. As such, the NUTW instead decided to march through the centre of Kirkcaldy.

This move was carefully calculated. On the one hand, it was a more deliberate – and public – show of strength than the planned sit in. Hundreds of residents across Kirkcaldy would see the strikers, causing reputational damage to the town’s beloved Nairn’s. On the other, marching through the town allowed workers to demonstrate against their employers legally; if they moved throughout the town, they would pass close by their workplaces, but not picket directly outside them.

The resulting march involved between 1500 to 2000 workers – about 90 percent of all Nairn factory employees. The strikers began near the floorcloth factory in Pathhead, before turning down Victoria Road. This lead them past the linoleum works, and the company’s head office at Braehead House. They then continued past what is now Kirkcaldy Galleries, and on to the Adam Smith Theatre.

The strikers outside the Adam Smith Theatre.

On the following day the strike had intensified, with the Motorman’s union joining with the NUTW. The Motorman refused to supply the linoleum industrial with oil, meaning that the workers who remained were unable to operate their machines. Production ground to a halt.

Such a work stoppage forced Nairn to enter into negotiations. In the interim, employees would return to work with the promise that they would not be “victimis[ed]” for striking. Between the 17th and 18th both sides laid out their demands. Nairn’s wanting to stop union activism from occurring, and to maintain control over assigning work. The NUTW wanted their union to be officially recognised and to guarantee scheduled meetings between representatives and the firm. On the 19th October, the Unions won out. Nairn’s agreed to recognise the NUTW, on condition that they did not promote union activity during work hours and that Nairn would be able to take in workers complaints and keep control of business management.

If you would like to learn more about the Fife linoleum industry, you can visit the Flooring the World exhibition at Kirkcaldy Galleries (15 November 2023 – 25 February 2024). Flooring the World is a two-year project exploring the history of the Fife linoleum industry. It is funded by the Esmée Fairbairn Collections Fund, which is run by the Museums Association.

This brilliant photograph below is part of a set of four in our linoleum collection, which document a strike from the worker’s point of view. It shows a group of men gathered around a hand-written sign, which reads: ‘9th day of strike. Morale excellent. We swear to fight till the end.’ Until recently, this was basically everything we knew about these images. As part of the Flooring the World project, we decided to do some research to find out more!

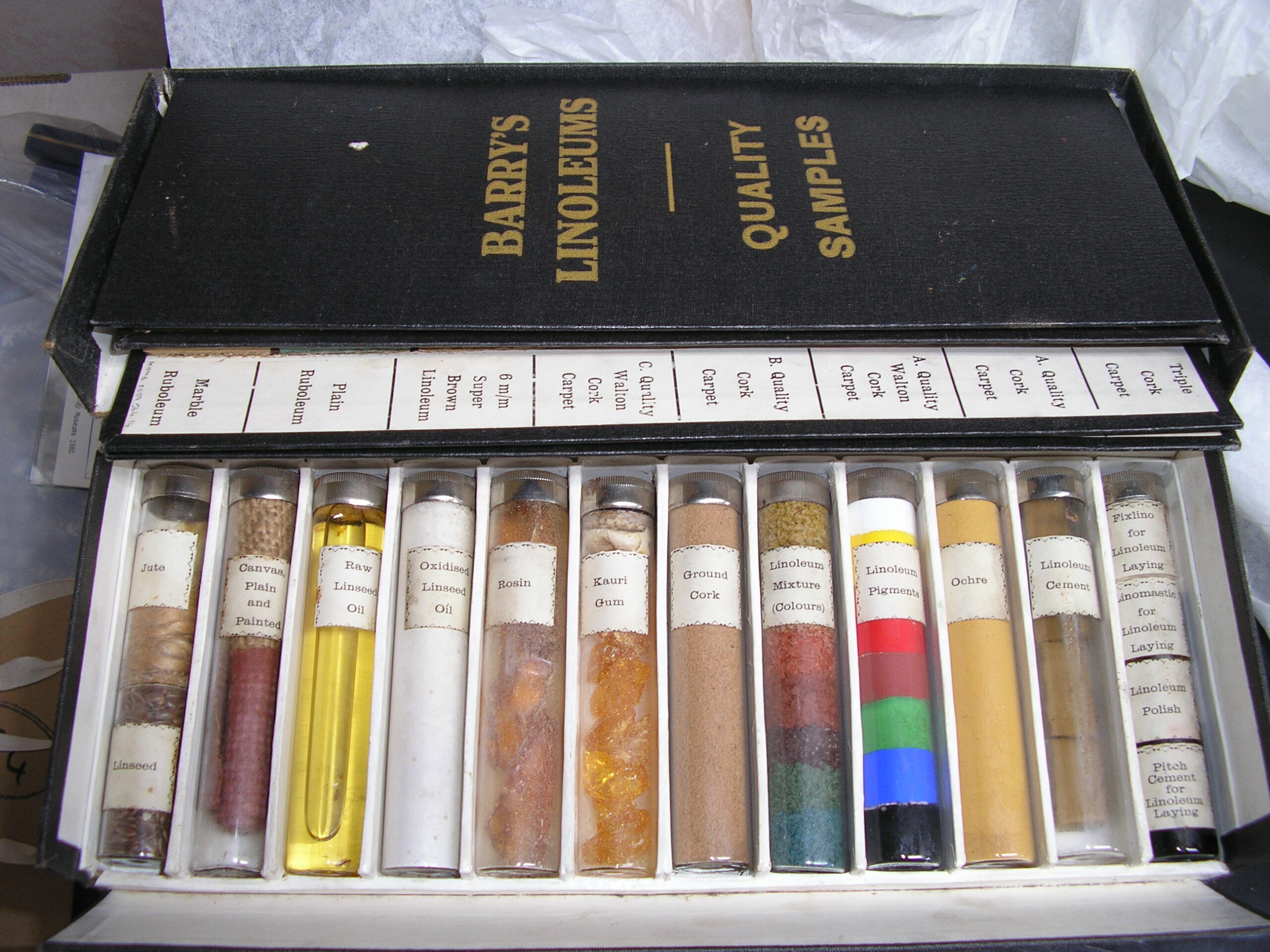

We knew that these photographs showed strikers at a French linoleum factory in the early twentieth century but were unsure exactly when and where they had been taken. We were also not sure how they were connected to our collections, but suspected that they were linked to one of Kirkcaldy’s two largest linoleum companies: Michael Nairn and Company, and Barry, Ostlere and Shepherd.

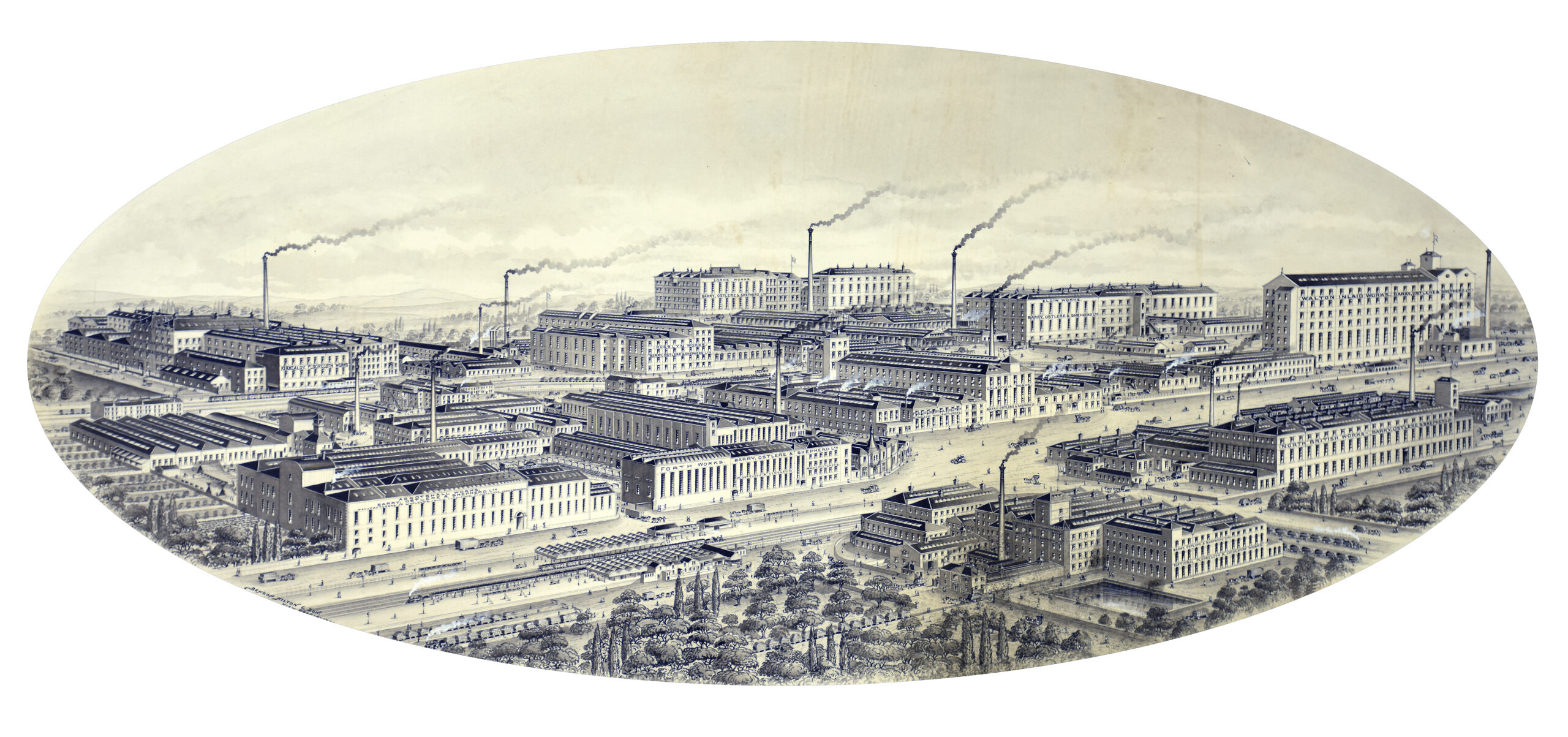

By the end of the nineteenth century, these companies had come to dominate the Fife (and by extension, the British) linoleum industry. Nairn’s was the town’s oldest firm, and had been growing its reputation since it started producing floorcloth in 1847. Barry’s was a relative newcomer, but – being formed from a merger between several of the town’s smaller firms – had effectively grown to a size where it could compete with Nairn’s by absorbing its own competition. Both firms operated multiple factories across the town: both had premises in Sinclairtown, while Nairn’s dominated the harbour and Victoria Road, and Barry’s surrounded Kirkcaldy’s central railway station.

This image shows all the factories operated by Barry, Ostlere and Shepherd in Kirkcaldy, 1905. The factories have been re-arranged to look as if they were all beside each other, but in reality were spread throughout the town.

Outside of Kirkcaldy, both Nairn’s and Barry’s also operated factories overseas, meaning that our strikers could have been employed in a French factory operated by either firm. In order to form a more certain link, and to learn more about our strikers, we’d have to look outside of our collections.

This photograph shows the in-house fire brigade employed at Nairn’s factory at Choisy-Le-Roi, France.

We began by searching Gallica, a database which allows you to search the collections of the French National Library (Bibliothèque National de France, or BnF). Initially, we limited the date range to 1900 – 1929. This was a rough estimate based on the clothes the men were wearing in the photographs; working class men’s fashion is very hard to date as it changes relatively little across a span of decades, but it can still sometimes provide you with an approximate idea. We then searched the database for the word ‘linoleum’ appearing in the same text as the word ‘grève’ (the French for strike).

This resulted in a few results! Sadly, most of these were newspapers or journals which featured adverts for linoleum alongside reports of strikes in other industries. While these were testament to the ubiquity of linoleum in the early 20th century, they did not necessarily help us to answer our strike questions!

Workers playing cards during the strike. The surnames and first initials of some of the strikers are written on the reverse of our prints. In future, it may be possible to learn more about them by using family history research skills.

However, one result did look promising. In an issue of L’Humanité – the official journal of the French Communist Party – dated to 7 March 1923, mentioned a strike at a linoleum factory in Le Houlme, Normandy, operated by La Compagnie Rouennaise de Linoleum. But what was the link between this strike, and our collections?

The answer lies in that busy time at the end of the 19th century when Nairn’s and Barry’s were consolidating their power. Barry, Ostlere and Shepherd was officially formed in 1899, by a merger between John Barry, Ostlere and Company, Shepherd and Beveridge, and the Kirkcaldy Linoleum Company – all of whom had been producing floorcoverings in the shadow of the older and more established Nairn’s. There was however a fourth company included in Barry’s DNA: a little Normandy venture called La Compagnie Rouennaise de Linoleum (CRdL).

The CRdL was established in 1897, two years before it became part of Barry’s. At the time of the merger, it employed approximately 150 people, which rose to around 500 by 1950. It is therefore likely that their workforce at the time of the strike was somewhere in the middle of this range. The image below shows 87 men gathered outside the factory gates, indicating that a significant proportion of the factory’s workers decided to take action against their employers.

2023 marks 100 years since the workers of Le Houlme went on strike!

The strikers’ demands were centred around their pay. Their employers had offered to increase their pay in the summer months, but not the winter, and this had been rejected. However, it is also possible that the connection with Fife may have added to the workers’ grievances. A report in our collection written in the 1950s by T J Cavanagh, one of Barry’s managers, noted that the French factory often had to make do with out-of-date equipment. When new machines were purchased, these were prioritised for Kirkcaldy who then sent their cast-offs to Normandy. It is possible that the feeling that the French factory was something of an after-thought may have been present in the 1920s, and contributed to the feeling of discontent among the workers.

We don’t know how long the strike went on for after the 11th day captured in the last photograph above. The next issue of L’Humanité reported that the Rouennaise strikers had been victorious – but this came just a few days after the original report of 7 March. This means it’s quite likely that it took a few days for the strikers to get in touch with L’Humanité – or perhaps they turned to the Communist party to increase pressure once the strike had gone on for longer than anticipated.

In either case, the workers were victorious! Their employers agreed to give them a pay rise of 175 cents per hour, holiday pay and to ‘keep all their pre-strike advantages’. This last is slightly ambiguous, though it was common for striking workers to request agreement in writing that they would not be prejudiced against for striking when they returned to work. It is possible that this clause was included to guarantee this kind of protection.

The CRdL continued to manufacture floorcoverings until 1968, some five years after Barry’s ceased production in Kirkcaldy (though the company survived until 1969 in Staines Middlesex, and until 1978 in Newburgh, Fife). Like many of Fife’s factories, it was fell victim to the falling demand for linoleum as alternative floorcoverings became cheaper to buy and easier to maintain.

_____________________________________________

Flooring the World is a two-year project exploring the history of the Fife linoleum industry. It is funded by the Esmée Fairbairn Collections Fund, which is run by the Museums Association.

![]()

Our linoleum collections consist of over 5,000 objects, documents and photographs, covering over 170 years of history. For this story, we’re heading all the way back into linoleum’s pre-history, to its origins in the Kirkcaldy floorcloth industry.

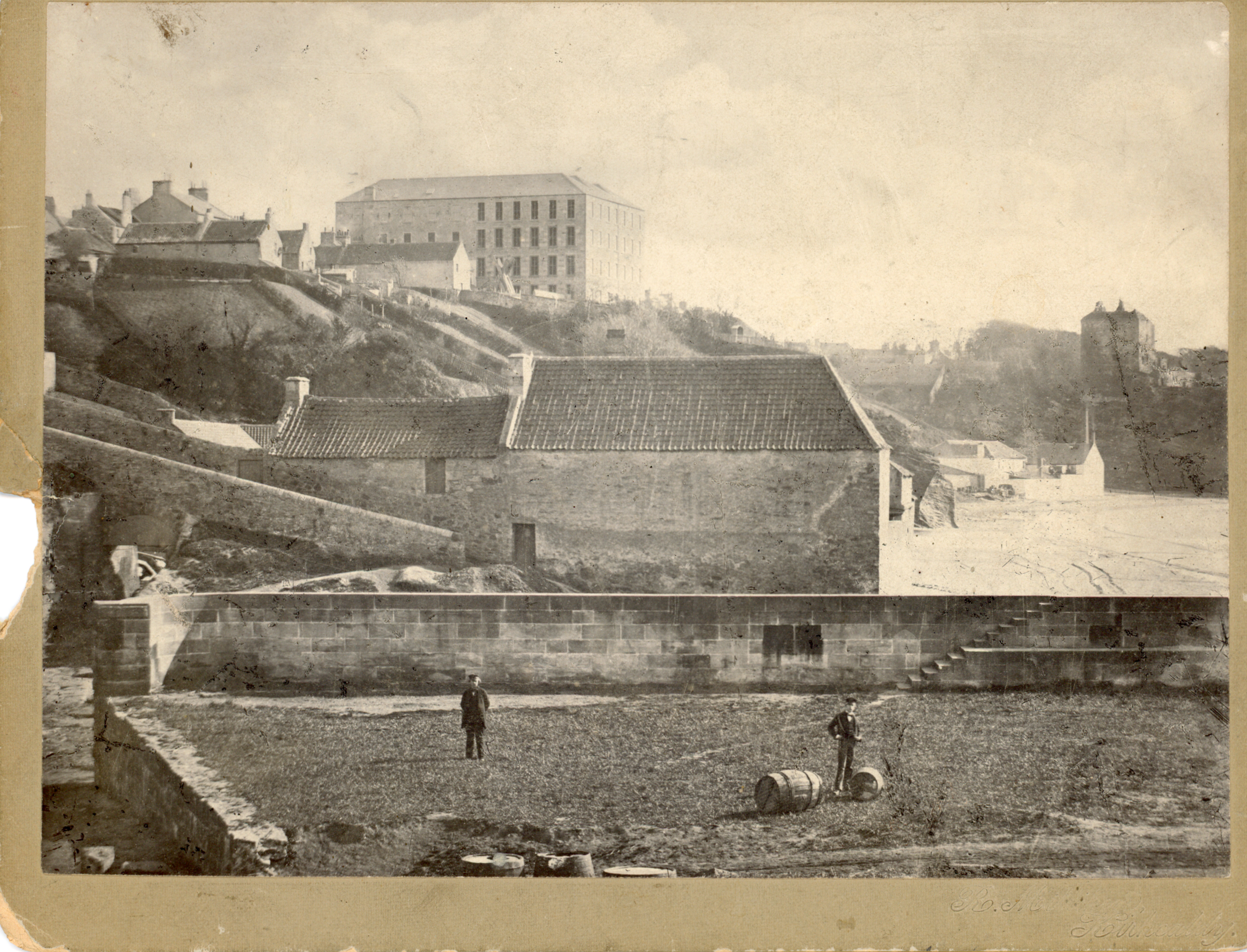

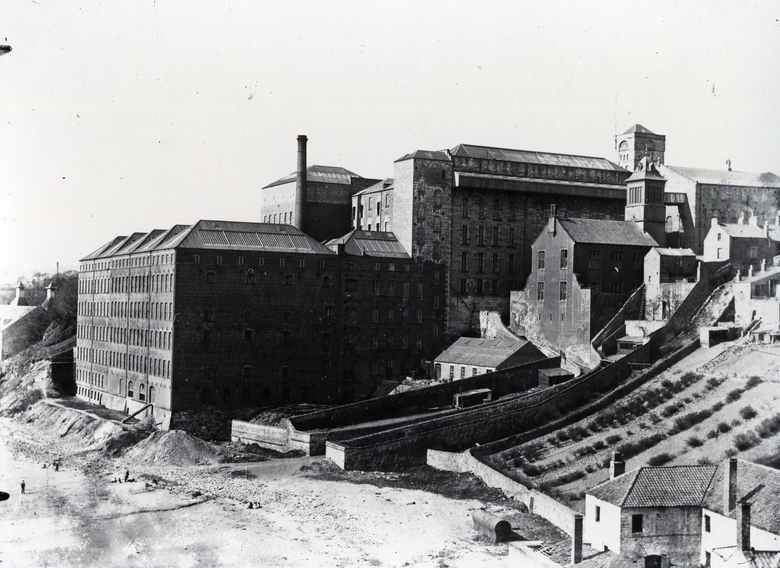

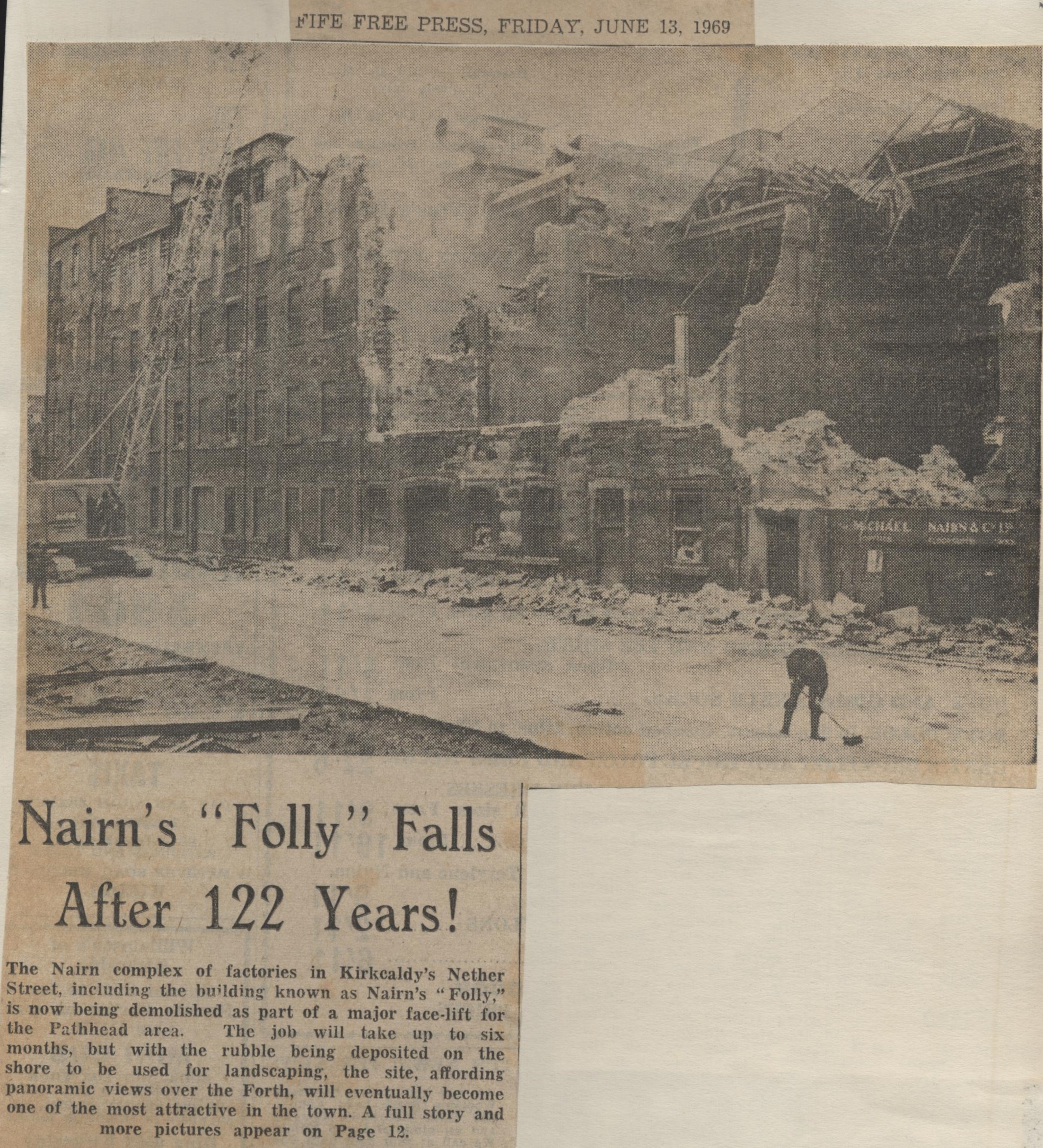

The first floorcloth factory in Scotland was built by Michael Nairn in the Pathhead area of Kirkcaldy. Known colloquially as ‘Nairn’s Folly’, this massive factory was the first stepping-stone in Nairn’s evolution from a small-scale canvas manufacturer to one of the most prolific producers of floorcoverings in the world.

A view of the beach below Ravenscraig castle. Nairn’s Folly is the large building on the top of the cliffs.

Floorcloth itself had existed for centuries; the earliest known reference to it in the UK is in the inventory of a house called Denham Hall in 1736! It was similar to linoleum, and was made of many of the same ingredients and using similar processes. A paste made from resins, cork dust, wood flour and coloured pigments was painted onto a canvas backing. These layers were built up on either side of the canvas, so that each side was smooth and waterproof. A patterned design would then be printed on the ‘top’ side. These could then be used, like rugs or carpets, to cover dirt, wood or stone floors.

For the first 30 years of their foray into floorcoverings, Nairn’s focused exclusively on floorcloth. From 1877, they produced both floorcloth and linoleum, until the former dwindled away in the first few decades of the 20th century.

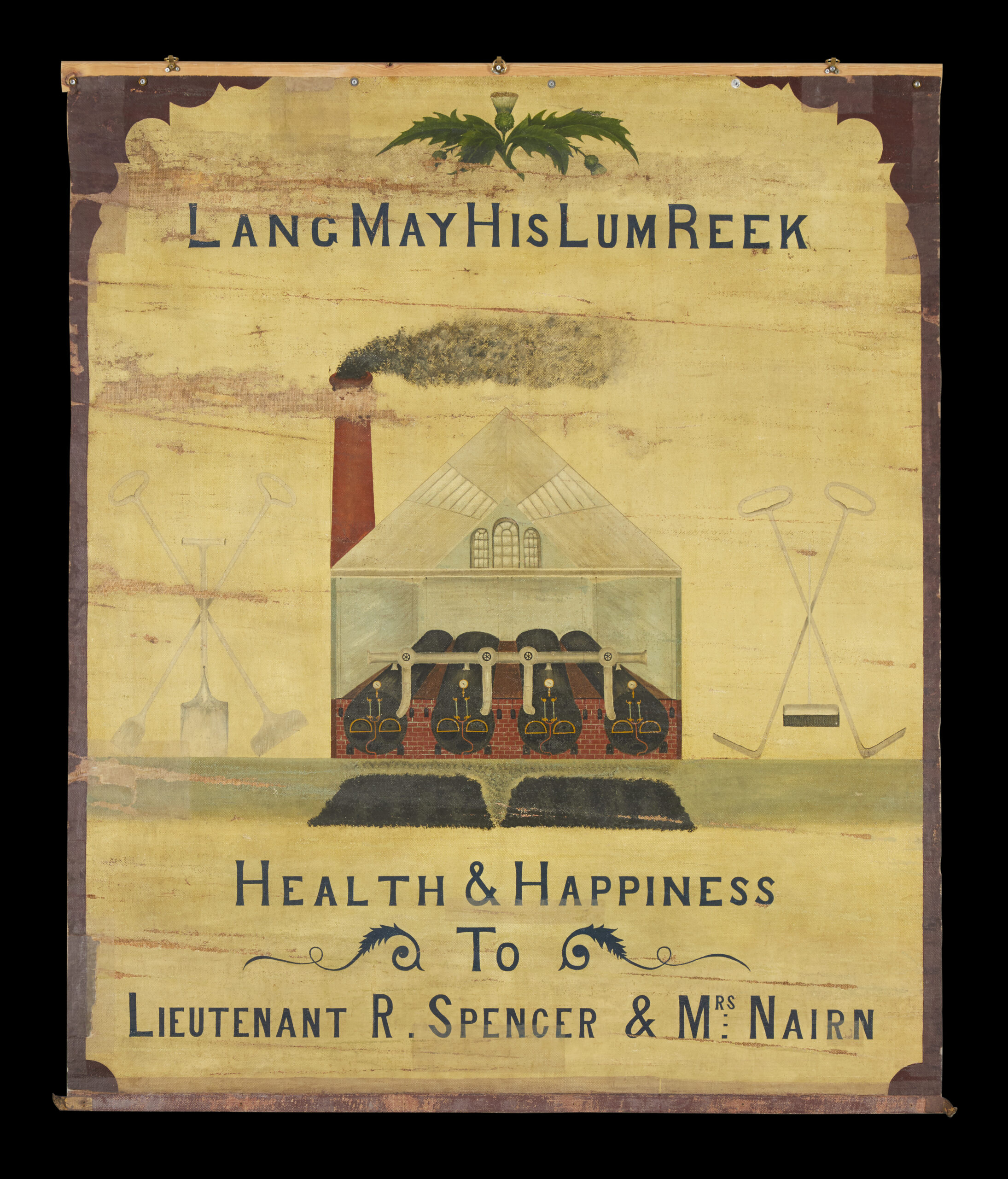

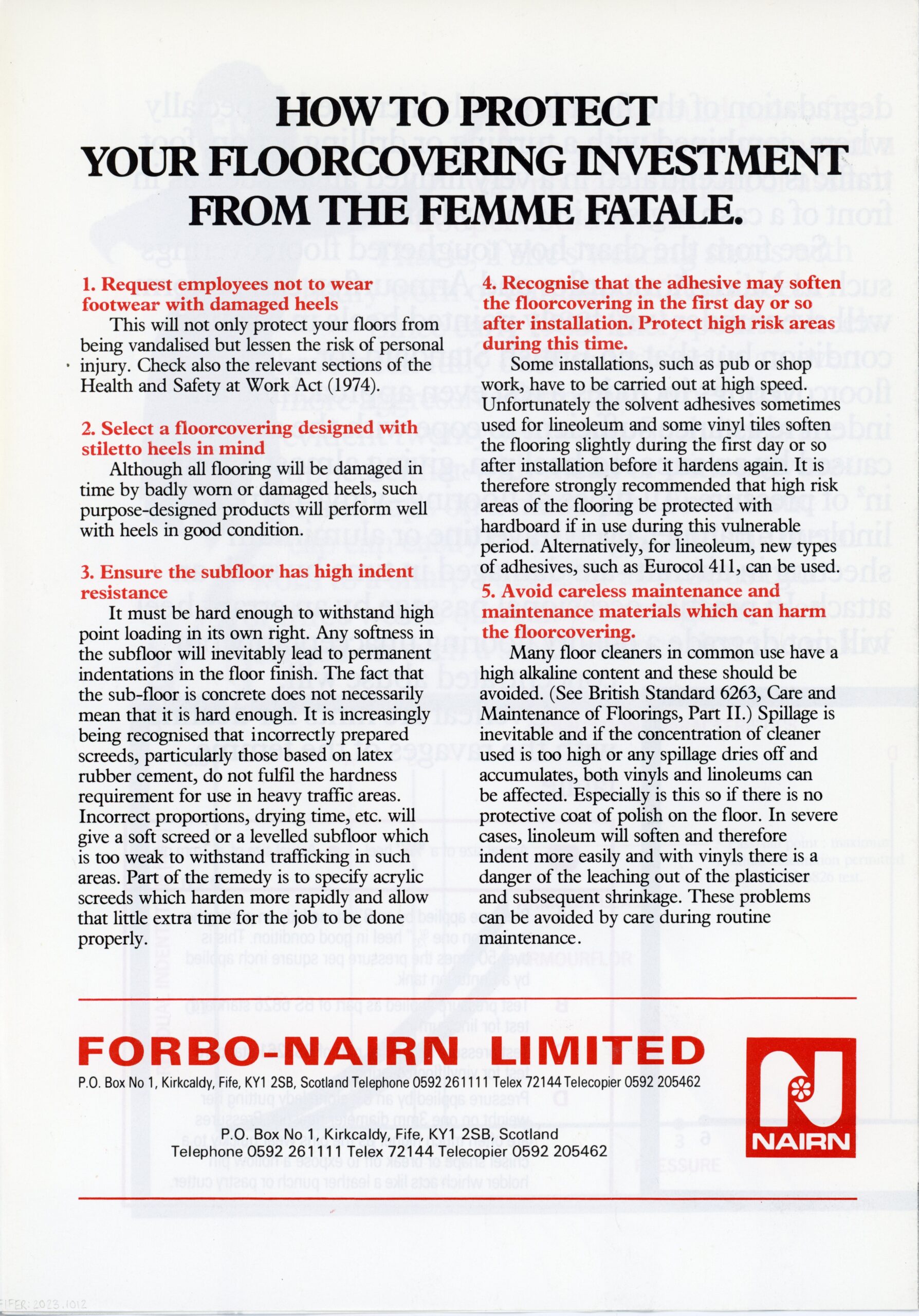

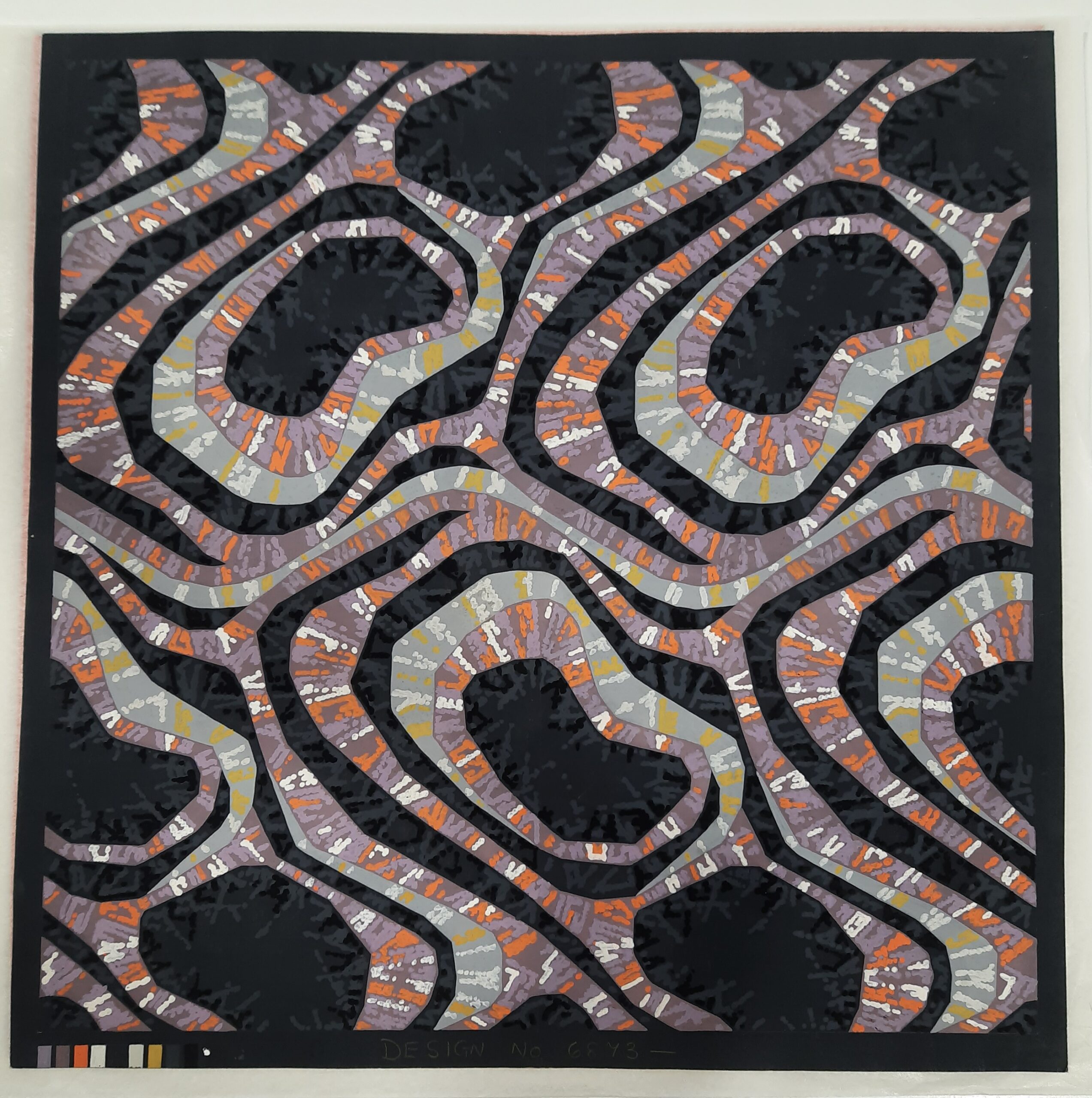

A floorcloth banner from our collection. The first image shows the design painted on the ‘bottom’ of floorcloth. The second shows the printed ‘top’, which would become the back of the banner when it was carried.

For Nairn’s however, floorcloth wasn’t just for floors. From the late 19th century up until the First World War, it was used to create a series of hand-painted banners, which were carried in processions by the workers. The patterned ‘top’ side of the floorcloth became the back of the banner, and the plain ‘bottom’ side was painted with a design and slogan. Usually, these praised the Nairn family or the products made by the company.

We know from photographs and secondary sources that dozens of different banners were made. Today, only five are known to survive – all in our collection. We are not currently aware of any other banners like this in the world, so it is possible that these are the only five in existence.

A floorcloth banner from our collection, created in 1907.

This banner was created by the engineers and fireman from Nairn’s Folly floorcloth works to commemorate the wedding of Robert Spencer Nairn on 6 July 1907. To mark the occasion, the Nairn family organised a workers’ excursion to their estate in Rankeilour (near Cupar, Fife). This would have been the first time this banner was carried.

A photograph showing the Nairn’s workers marching with floorcloth banners during their 1903 excursion.

At the beginning of the day, Nairn’s workers gathered at each of their places of work across the town. The first group then set off from the Canvas works, marching towards Nether Street where their colleagues from the Floorcloth Works would join them as they passed Mid Street. An article in the Fife Free Press (dated 13 July 1907) records that all the banners in our collection were made and carried by the Floorcloth Works group, who also wore floorcloth caps and sashes.

After a short interval, the Linoleum workers would join in behind them, led by a foreman carrying a sword. The Trades Band played at the front of the procession, and the Pathhead Band played at the back.

The itinerary produced for the 1907 Summer Excursion.

All workers then boarded special trains at Sinclairtown station, where they were taken north to Rankeilour. In total, over 2,400 people attended, as each worker was permitted to bring a family member or friend along with them.

On arrival there, they enjoyed an early lunch (served at 11:30), followed by dinner at 16:30. In between, they played the sort of games you’d expect at a summer fete (including the sack race and the egg and spoon race) and a Highland games (including a caber toss).

The Nairn’s workers at Rankeilour during their 1905 Summer Excursion.

We know from other excursion itineraries in our collection that these excursions happened on at least two other occasions during this decade – first in 1901, and next in 1905. However, it is possible that this trip to Rankeilour may have been the last in which our floorcloth banners were used.

This banner was conserved in 2020, and is currently on display at Kirkcaldy Galleries.

We know that this banner was carried along with ‘Lang May His Lum Reek’ in 1907. From conservation in 2020, we know that this banner had the date on it repainted each time it was carried. As the date visible was the last time it was updated, it is possible that this was its final outing. If this is the case, then it is likely that our ‘Lang May His Lum Reek’ banner was also only carried on this single trip.

Interested in seeing our floorcloth banners in person?

‘First in the Field’ is part of our permanent displays in Kirkcaldy Galleries and can be seen in the Moments in Time gallery, opposite the café.

‘Lang May His Lum Reek’ will be going on display as part of the Flooring the World exhibition, which will open at Kirkcaldy Galleries on 25 November 2023.

It is also possible to see two of the three remaining banners at our collections store in Bankhead, Glenrothes. You can make an appointment to see them by e-mailing museums.enquiries@onfife.com

_______________________________________________

Flooring the World is a two-year project exploring the history of the Fife linoleum industry. It is funded by the Esmée Fairbairn Collections Fund, which is run by the Museums Association.

![]()

The First and Second World Wars had a profound impact on daily life around the world, and Fife was no exception. In particular, the outbreak of war – and the peace in between – provoked changes to the types of jobs which were done in Fife, and the kind of people who did them.

In this blog post, we’ll explore how the World Wars changed the role that women played in the Fife linoleum industry by examining photographs from our museum collections.

If you would like to learn more, we’ve just installed a temporary display on this subject in our Moments in Time gallery at Kirkcaldy Galleries. This will be on display until the end of August 2023, and you can see it any time during the Galleries’ regular opening hours.

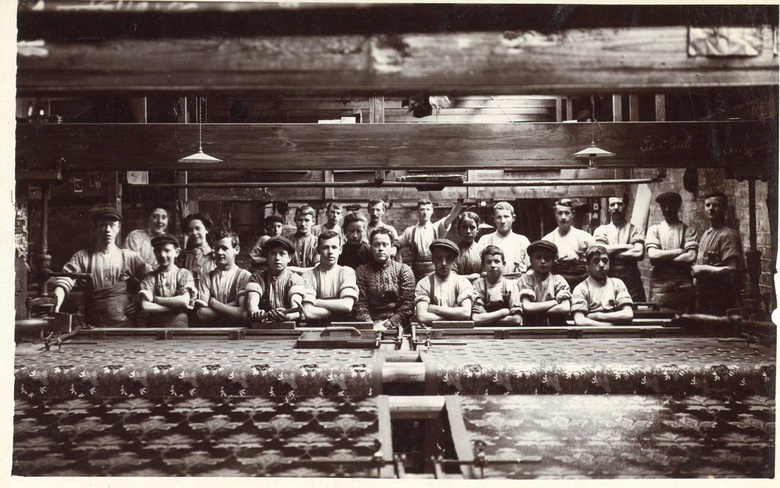

Image: A group of floorcovering workers in the printing loft of the Tayside Floorcloth Company, c.1890 – 1910. (CUPMS1990.0070)

The First World War is often understood as the time when women first entered the workforce en masse, dramatically changing the demographic of – particularly – industrial workplaces. However, that is not to say that women were entirely absent from the workplace before this time.

Women – particularly poor women, women of colour, and women from otherwise marginalised communities, such as recent immigrants – have always had to work to support themselves and their families. Though many felt that certain types of work (or, perhaps, even the idea of work at all) were inappropriate for members of the ‘fairer sex’, eschewing employment was a luxury that few women could afford.

This photograph shows workers in the printing loft at the Tayside Floorcloth Factory, Newburgh, probably at some point between 1890 – 1910. In it, we can see five women and nineteen men and boys. This suggests that, although they were outnumbered, women were still present, and in some cases even represented a significant proportion of the workforce.

We don’t know the specific professions of the people in this photograph. Nonetheless, it does seem likely that they were photographed in the space that they regularly worked, and therefore that this image shows a team largely made up of printers. This indicates that – in at least some workplaces – women were not segregated from men, that they worked in the same spaces as them, and potentially did the same or similar roles.

As we will see in later images, this was not necessarily consistent across the Fife linoleum industry. However, this photograph indicates that conditions like these were not unheard of, even if they were not the norm.

Image: A team of workers in Kirkcaldy in one of Barry, Ostlere and Shepherd’s factories, Kirkcaldy. 1914 – 1918. (KIRMG:1991.0231)

In January 1916, the British Government passed the Military Service Act, which required all men aged between 18 and 41 to join the Armed Forces. This meant that a new workforce had to be found to work in the jobs they left behind.

Skilled, conscription-aged men were replaced with unskilled and semi-skilled women workers, who learnt their new trades on the job. The men who remained were older and often held senior or managerial roles due to their greater lengths of experience.

Across the country, many teams working in factories would have therefore looked something like this. This team made up almost entirely of women, apart from the three men who appear to be above conscription age.

Another notable thing about this image is that some of the women are wearing trousers. This is very unusual; in the vast majority of the photographs in our linoleum collections, working women are shown wearing skirts and dresses. This ‘masculine’ dress-code was again temporarily permitted during the war. Women could dress ‘like men’ while they were doing ‘men’s work’ – but both of these things were understood as strictly temporary measures.

Sadly, we do not know what this team was working on at the time they were photographed. It is possible that they were manufacturing munitions and other goods required by the war effort.

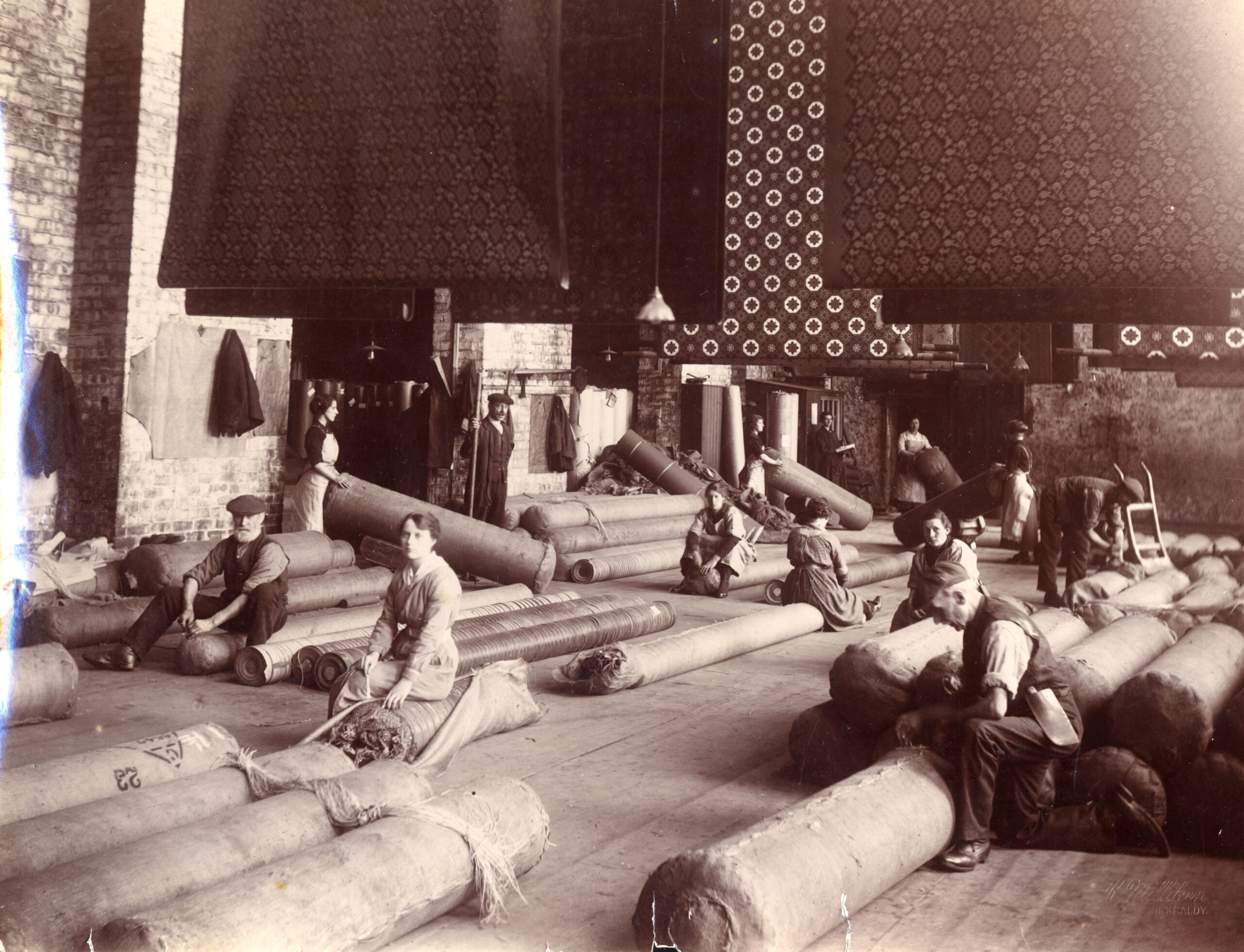

Image: A linoleum despatch room, Kirkcaldy. Of the photographs in our collections which show workers in linoleum factories during WWI, the majority were – like this one – taken in factories operated by Barry, Ostlere and Shepherd in August 1918. (KIRMG:1986.0097)

Many of the women employed in industry during WWI found themselves manufacturing products for the war effort. However, many factories also continued – at least in part – to make whatever they produced during peace time.

This photograph shows workers in the despatch room at one of Barry’s factories, preparing finished linoleum for delivery. From this, we can deduce that linoleum production – for the domestic market – continued through the war, and that women were involved in its manufacture.

Image: Women stoking the boilers in one of Barry, Ostlere and Shepherd’s factories, Kirkcaldy. August 1918. (KIRMG:1986.0095)

Aside from weapons and linoleum, there were also some jobs that simply had to be done regardless of what was being done in the rest of the factory. The women in this photograph are shown stoking the boilers – a task which had to be completed day in, day out, come rain or shine.

Image: Canteen staff at Michael Nairn and Company Limited, Kirkcaldy. 1935. (KIRMG:1983.0633)

Following the end of hostilities, the British government, Trade Unions and other influential groups were eager for working life to get back to normal as soon as possible. This meant women giving up their jobs in favour of the men who had vacated them and, preferably, returning to domestic work (either unpaid in their own homes, or paid in the houses of others).

Nonetheless, through both choice and necessity, some women did remain in the workforce. Usually, women were encouraged into roles which were extensions of the sort of work they would do at home. This included cleaning and, like the canteen workers pictured in this image, cooking.

Image: Clerical staff at one of Barry, Ostlere and Shepherd’s factories, Kirkcaldy. 1920s. This photograph is from a series in our collection which show teams of Barry’s workers. (KIRMG:1980.2620)

There were a few exceptions to this rule, including clerical work. Since the 1880s, administrative tasks had increasingly become associated with women workers. Over the next few decades, this would continue to the point where it became almost quintessential. Even today, we still associate these kind of roles – secretaries, assistants and receptionists – with women.

There are a few reasons for this. Firstly, the typewriter was a new piece of technology, which required previously non-existent skills to operate. As such, women could take up this role without having to face the stigma of having ‘taken a man’s job’.

Secondly, compared to other types of work, administrative tasks were relatively clean and quiet. This dispelled fears from moralists that work was unladylike, and would naturally coarsen women until they were uncivilised (or worse, unattractive to men). A typist could carry out her work and still embody the traits which – in the late 19th and early 20th centuries – were seen as synonymous with womanhood.

Finally: size mattered. As women, on average, had smaller hands than men, it was assumed that they would naturally be more dextrous. Women were naturally suited to typing, because their dainty fingers would be better suited to operating the machine.

Image: Twins Catherine and Janet Fortheringham making inlaid linoleum. Though this photograph dates from c.1959 – 1964 the task was associated with women long before this. (TEMP:2012.4426)

Strangely, the assumption that smaller hands were faster, more dextrous hands may also have led to another job in the linoleum industry becoming the preserve of women.

Throughout the history of the linoleum industry, the production of inlaid linoleum has been a task primarily associated with women. This was a highly skilled process, by which pieces of different coloured linoleum were fitted together to make a pattern. Unlike printed designs, inlaid designs would remain intact regardless of how much the floorcovering was worn down – the colour of each piece went all the way to the back, so the design was much longer lasting.

Image: Workers making fuel tanks for Halifax bombers at one of Michael Nairn and Co. Ltd.’s factories, Kirkcaldy. 1939 – 1945. (TEMP:2012.4431)

When WWII broke out, women once again returned to Kirkcaldy’s factories.

This time, there was a greater focus on producing goods for the war effort. Women working at Nairn’s manufactured fuel tanks for Halifax bombers, as well as munitions.

In 1946, Nairn’s published a book celebrating their workers’ contributions to victory. In this, they stated that perhaps their biggest contribution was the production of anti-gas fabric, which was made into capes and gas-masks. The fabric had to be impregnated with linseed oil, a key ingredient used in the manufacture of linoleum (and which gives the floorcovering its name: ‘lin’ meaning linseed and ‘oleum’ meaning oil). In the book, Nairn’s wrote that this was a decisive factor in the Allies victory. As the Nazis could not manufacture gas-proof textiles in sufficient quantities, they never used gas in air raids for fear of retaliation. As such, they were unable to use a decisive weapon which may have given them the upper hand.

If you would like to learn more about Women, War and Linoleum, we’ve just installed a temporary display on this subject in our Moments in Time gallery at Kirkcaldy Galleries. This will be on display until the end of August 2023, and you can see it any time during the Galleries’ regular opening hours.

_______________________________________________

Flooring the World is a two-year project exploring the history of the Fife linoleum industry. It is funded by the Esmée Fairbairn Collections Fund, which is run by the Museums Association.

![]()

From the 1950s, linoleum faced one of the greatest challenges in its history – one which influenced the way the product was marketed for decades.

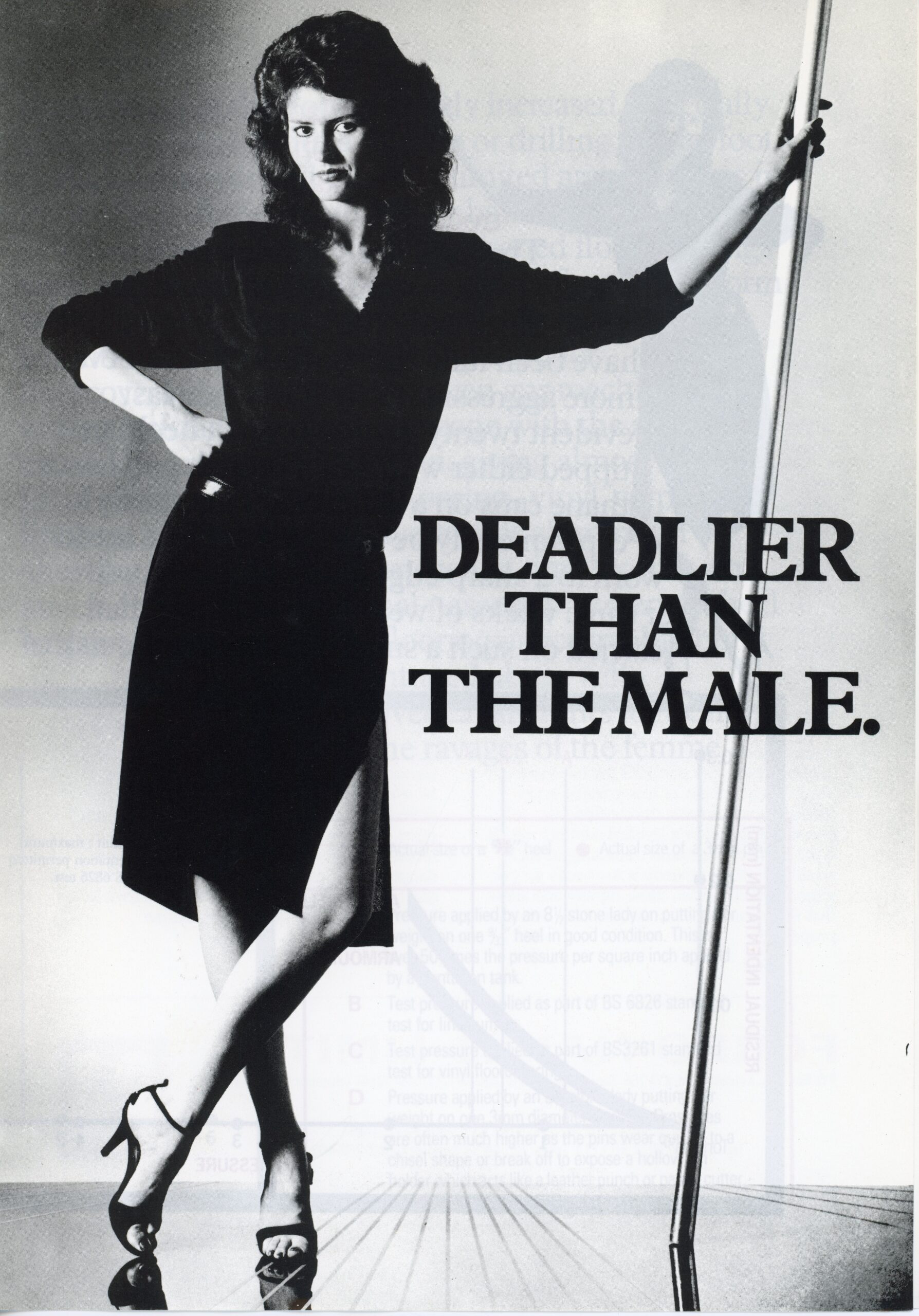

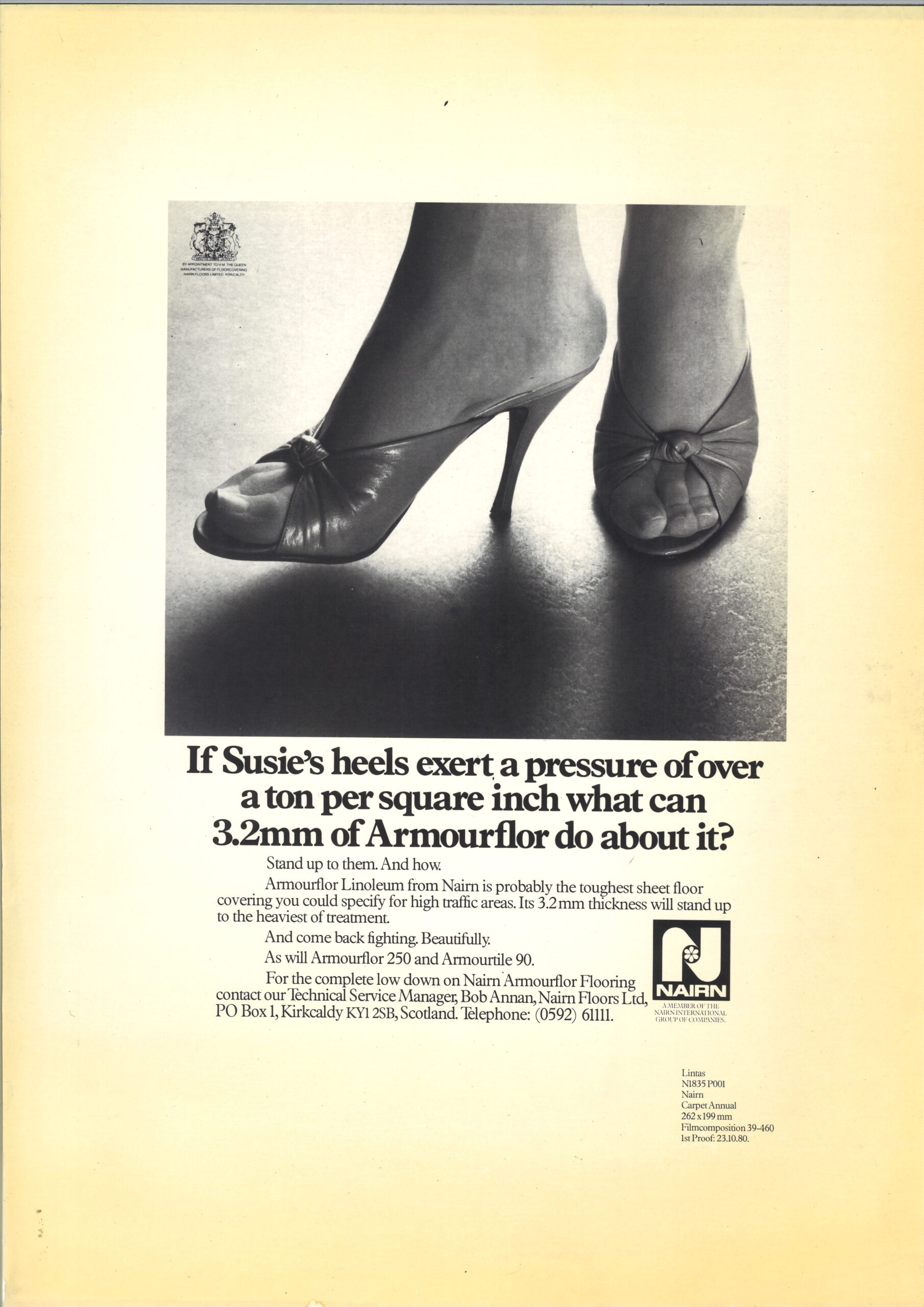

Let’s start with a image. A black and white photograph of a woman, standing in a non-descript space. Below her is a slogan: Deadlier than the male. But the words don’t refer to the woman, or to her fluffy hair, or her dark dress, or her direct stare. Instead, they’re directed at what’s on her feet: a pair of strappy, open-toe shoes with a short, thin heel.

Image: Promotional booklet produced by Forbo-Nairn, c.1985.

The stiletto heel was first developed in the 1930s, though their original inventor is disputed. The design was made possible by the use of a thin metal core within the heel which gave it its strength and structure (as well as its name – a stiletto was a thin dagger which came into use in 15th century Italy). In the 1950s, this design was popularised French designers Andre Perugia and Roger Viver. By the 1960s, the stiletto heel had spread across Europe and North America, and was synonymous with style, sex appeal and glamour.

However, the rise of the stiletto was not just a concern for the fashion conscious; in the mid-twentieth, stiletto heels were on the minds (and in the nightmares) of every linoleum manufacturer in the world.

Heeled shoes had been walking over linoleum for as long as it had existed. The difference here was that the thin heel of the stiletto concentrated the wearer’s weight in a far smaller area, exerting a far greater pressure on the floor beneath. It is estimated that a stiletto heel worn by a person weighing 65kg exerts twelve times the pressure of a four-tonne elephant standing on one foot.

These high pressures meant that wearers left small indentations in linoleum floors as they walked. The increased popularity of stilettos, alongside the ubiquity of linoleum in both public and private buildings, meant that the damage was apparent to everyone. As lino’s reputation came under fire, both manufacturers and consumers became concerned about the longevity of the previously reliable floorcovering.

As such, manufacturers began to fight back with advertising. Theoretically, these stressed improvements to linoleum in the face of the new challenge of stilettos. In practice, while demonising the shoes they also laid the blame squarely at the heeled feet of the women who wore them.

Stilettos had very quickly become symbols of femininity to the point, even acting as a shorthand for signalling gender; for example, Minnie Mouse is essentially identical to Mickey, except for her high heels. Damage done by heels then, was damage done by women. Linoleum under attack from not just a shoe, but from an entire gender.

The rise in the popularity of stiletto heels came at a time when women were entering the workforce en masse. They were working in larger numbers, and in more diverse roles than ever before. At the same time as many were becoming concerned about the impact of shoes on linoleum, others were worried about the impact of this social change on the established order of things.

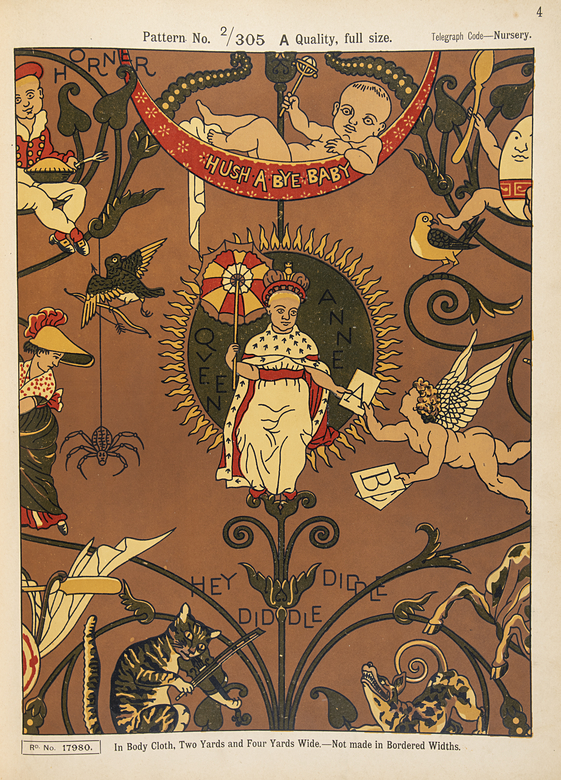

Let’s return to our advert. On the reverse, it includes a series of tips for protecting floorcoverings from the femme fatale. While most of these concern the floorcoverings themselves, the first tip simply suggests that stilettos be banned from the workplace. Dress-codes like this had been prevalent in offices since the 1950s, and were always enforced with the express desire of protecting floorcoverings. However, as stilettos had become very much symbolic of women as a whole, perhaps we can also see this trend in the context of anxieties over women’s liberation. Was the desire to have no stilettos in the workplace also partly a desire to have less women in the workplace too?

It would be wrong to suggest that linoleum advertising was in any way leading the charge when it came to sexism. However, these adverts can be seen as artefacts of a general perception of gender which – though it did not raise eyebrows at the time – now seems both dated and problematic.

________________________________________________

Flooring the World is a two-year project exploring the history of the Fife linoleum industry. It is funded by the Esmée Fairbairn Collections Fund, which is run by the Museums Association.

![]()

As we reach the end of the first year of the Flooring the World project, curator Lily shares some of the things the project has achieved over the last twelve months.

February

Image: Block made up of layers of ink. FIFER:2022.0184

One of the first things I did when I joined OnFife was visit the archive at the Forbo Factory on Den Road. The firm, initially as Michael Nairn’s and then to Forbo through a series of name-changes and mergers, has been producing floorcoverings in Kirkcaldy since 1847. They have offered their entire archive to us as part of the project, and I’ve spent a lot of time this year working through their amazing objects, documents and photographs deciding what to bring into our collections.

I accessioned this strange object after my first visit. It’s a block made up of layers of ink used to print designs on linoleum. It was cut from a spot under the floorboards in one of the – now demolished – Nairn’s printing lofts – over the decades, waste ink had dripped between the boards and built-up layer by layer. This block is a literal slice of history.

Image: RMS Queen Elizabeth, made out of linoleum. FIFER:2022.0147

Another new addition to the collections was this brilliant picture made of out linoleum. It shows the ship the Queen Elizabeth at sea, and was probably made in the late 1930s. We don’t know who made it, but suspect it was probably created in Fife. Read our post on this curious object to find out more.

I also got the change to visit Newburgh, another key site in the story of the Fife linoleum industry. While the factory buildings which made up the Tayside Floorcloth Company complex are now gone, the imprint of the industrial is still visible in the town. One place you can find a trace of it is in the Laing Museum – the patterned floor of the museum is original printed floorcloth which was laid in the 1890s.

Image: Floorcloth at Laing Museum, Newburgh

March

Image: Page from a pattern book. FIFER:2022.0150

In March, using funds provided by the Friends of Kirkcaldy Galleries, we had some of the objects in our collection photographed. Some of these – like the pattern book above – were new arrivals from the Forbo archive. Others, like the medal below, had been in our collection for some time. Medals like these were awarded to manufacturers at World’s Fairs and Expositions during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Perhaps the most famous of these was the Great Exhibition in London, 1851 – sometimes known as the ‘Crystal Palace’. Nairn’s were unlucky at this fair, but took notes on the products displayed by other floorcovering manufacturers to improve their processes. The research paid off, and for years afterwards they regularly returned home from these trips with a brace of accolades.

Image: Linoleum medal, brass, Allgemeine Deutsche Patent und Mustedrschutz Ausstellung in Frankfurt A. M. 1881, M Nairn & Co. TEMP:2011.1529

April

Image: Floorcloth banner. KIRMG:1983.0078

April saw the long-awaited return of one of our gorgeous floorcloth banners to Kirkcaldy Galleries. This banner went out for conservation before the start of lockdown in 2020 but, in order to keep everyone safe, it wasn’t possibly to reinstall it until 2022. The banner is one of five known to exist – all of which are in our collections. It was created by workers at Nairn’s at some point between 1900 – 1905, with a design painted on the plain underside of a printed floorcovering. Its conservation was generously funded by the Friends of Kirkcaldy Galleries.

Image: Back of the floorcloth banner. KIRMG:1983.0078

I also changed over the display in our Moments In Time case in Kirkcaldy galleries. At the beginning of the project I set myself the (perhaps overly ambitious goal) of changing the objects in this case once every three months. I began with a selection of objects from the Forbo archive, including the paint block I mentioned above.

May

In May I had the opportunity to share the project with other people working in museums across Scotland. I gave a presentation at the Scottish Museum Federation’s annual conference, introducing them to the wonderful world of linoleum and sharing the work that had been done so far. I also got the chance to show National Trust for Scotland curators Antonia Laurence-Allen and Emma Inglis (curators for Edinburgh and East, and Glasgow, respectively) around our stores. We spoke about the fascinating history of linoleum in Scottish houses, and talked about places where it can still be seen in situ today.

June

Image: Linoleum lent to V&A Dundee. FIFER:2022.0167

In June we had a visit from staff from V and A Dundee, who selected some samples of linoleum to go in their exhibition Plastics: Remaking Our World. Linoleum is not a synthetic plastic, but a biodegradable substance made of natural materials derived from plants. The objects were included to help illustrate some of the first materials which were designed to solve the same problems which were later resolved by plastic – perhaps by revisiting these older materials we can find an answer to the problems plastic in its turn has caused. These samples will be coming back to us soon, but you can still see some gorgeous inlaid lino in their Scottish Design gallery.

Image: Linoleum sample on long-term loan to V&A Dundee. FIFER:2017.0016

I also got a chance to write up some research I’d been doing, inspired by the many beautiful linoleum designs in our collections which were clearly intended for children’s rooms. Most of the patterns in our collections – be they in books or samples – are fairly neutral, and would be suited to any space. The exception is a small group of very intricate, complicated designs featuring characters from nursery rhymes. I wanted to find out more, and if you do to, then you can click here to read all about it.

Image: In a pattern book produced by the Kirkcaldy Linoleum Company, 1876 – c.1900. FIFER:2022.0150

July

Shh! In July I was invited along to talk about linoleum for a forthcoming TV programme. I can’t tell you too much about it yet, but watch this space!

By July, it was already time to change the Moments In Time case. This time I opted to go for a selection of objects and photographs which told the story of Kirkcaldy linoleum in the 1960s – a dark decade which saw the loss of much of the city’s industry. I wanted to try something a little bit different, so supported this display with a playlist of songs which were popular at the time, to help conjure up memories of times gone by. You can listen along here.

Image: 1960s linoleum.

August

In August I was lucky enough to record the first oral history of the project. This involves going out to meet people who worked – or who had relatives who worked – in the linoleum industry, and speaking to them about their working life. These recordings become a part of our collection, and can be accessed by anyone interested in the industry to help them to learn more about the lived experience of those would made the linoleum industry possible.

For my first oral history recording, I spoke with someone who designed patterns from linoleum at Newburgh, first for the Tayside Floorcloth Company, and then for Barry Staines. They also kindly donated some of their hand-painted designs, which were created between 1959 and 1969.

I am hoping to record even more oral histories in 2023. I’d like to speak with anyone and everyone who worked (or who had family members who worked) with linoleum, or anyone who has a story to tell me about the industry in Fife. I’d be particularly keen to hear from those who have memories of the industry in Falkland, as this is somewhat underrepresented in our collections.

If you’d like to learn more, please get in touch using the contact details at the bottom of this post.

September

Image: Newburgh Ancestry and Family History Society visit.

In September, we welcome the Newburgh Ancestry and Family History Society to our collections stores at Bankhead. The group were there to see a selection of objects relating to Newburgh, including some of the wonderful photographs in our collection showing the town’s linoleum industry.

October

Patented!

I was invited to speak about the history of lino on Patented, a podcast produced by History Hit. She chatted with host Dallas Campbell about how linoleum was invented, and how – via a ground-breaking legal trial – it made its way to Kirkcaldy.

We also welcomed the first of our linoleum store tours! This meant welcoming two groups to take a guided tour around our collections store at Bankhead, before giving them the chance to get up close and personal with a selection of objects, documents and photographs from our linoleum collection. This included a chance to see the newly conserved Paolozzi elephant (more about them in December!).

Finally, I changed over the Moments in Time case in Kirkcaldy Galleries to feature a display about the in-house fire brigades employed by linoleum factories. You can learn more about them in this blog post.

Image: Collections store tour.

November

November saw another round of tours, with yet more visitors getting to see our collections in the flesh. We’re looking forward to running more of these in 2023, so if you’re interested in coming along please get in touch using the contact details at the bottom of this article.

I also collected another load of boxes from the Forbo Archive – these were the last to enter our collection this year. In total, we accessioned over a nine hundred objects, documents and photographs from the Forbo Archive in 2022 – and there is lots more to come in 2023!

One of my favourite things from the archive is this photograph of two men holding a floorcloth banner, probably dating to c.1900-1909. The banner is now lost, so this photograph is our only record of it.

Images: Photograph of workers with a floorcloth banner. TEMP:2012.4439

December

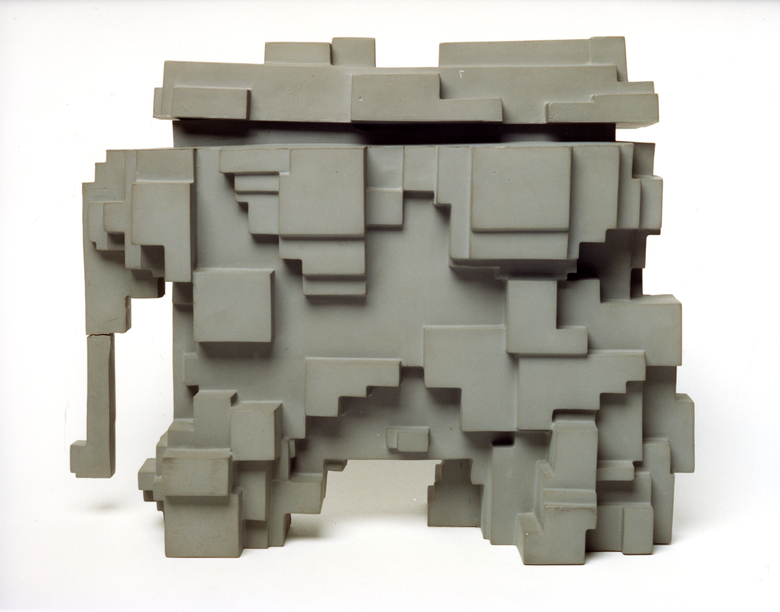

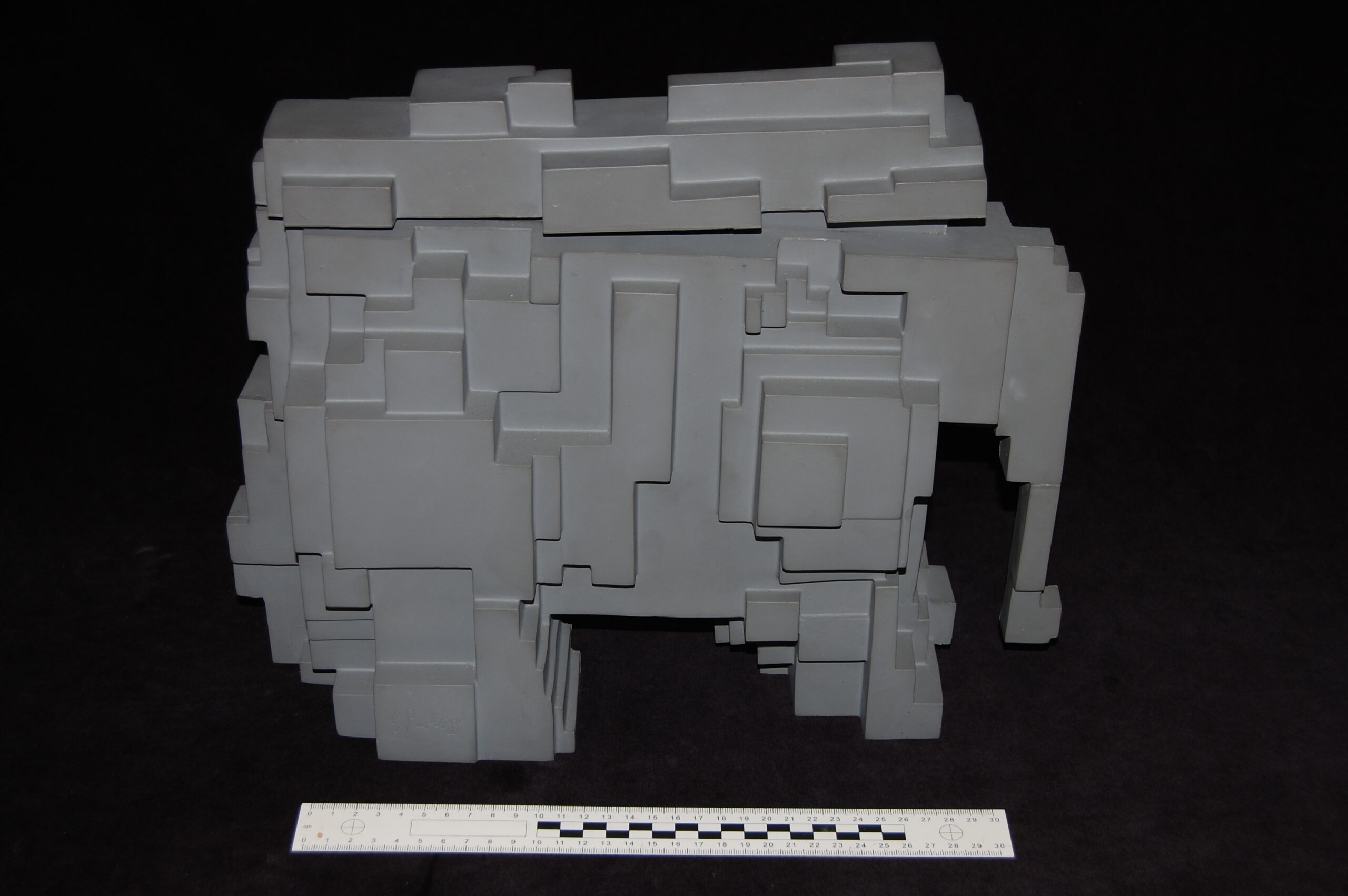

Image: Paolozzi elephant. FIFER:2022.0235

Remember those elephants I mentioned earlier? Well, following conservation they both went on display in Kirkcaldy Galleries, where you can see them until the beginning of March 2023. If you’d like to learn more about these peculiar pachyderms, check out our previous blog post here.

We also welcomed a piece of William Morris patterned linoleum into our collections. The sample was a gift from the William Morris Society Hammersmith, and is a piece of the only linoleum ever created from the Morris Company. It is believed to have been manufactured in Kirkcaldy in the 1870s. We haven’t had a chance to have this photographed yet, but are looking to have it on display in Kirkcaldy Galleries later in 2023.

January

In January I installed a new display in the Moments in Time gallery, this time featuring buildings associated with the linoleum industry which were demolished during the 20th century. I’ll be changing this display again in April – so watch this space!

What’s next?

2023 is going to be a very exciting year for the Flooring The World project. We’ll be working with communities in Newburgh and Falkland, as well as volunteers in Kirkcaldy, on some exciting projects which we’ll share later in the year. Plus we’ll be working on our exhibition, which will open at Kirkcaldy Galleries in November.

We’ll also be continuing to improve our collections, and to collect oral histories from those with first or second hand experience of the linoleum industry. If you have memories you’d like to share, please get in touch – no story is too small!

If you’re interested in being involved with the Flooring the World project, you can reach me by e-mailing lino@onfife.com, or by calling 07548777008. You can also keep up to date with the project by following the project page on Facebook, or by following Kirkcaldy Galleries and OnFife Museums on Instagram, Facebook or Twitter.

________________________________________________

Flooring the World is a two-year project exploring the history of the Fife linoleum industry. It is funded by the Esmée Fairbairn Collections Fun., which is run by the Museums Association.

![]()

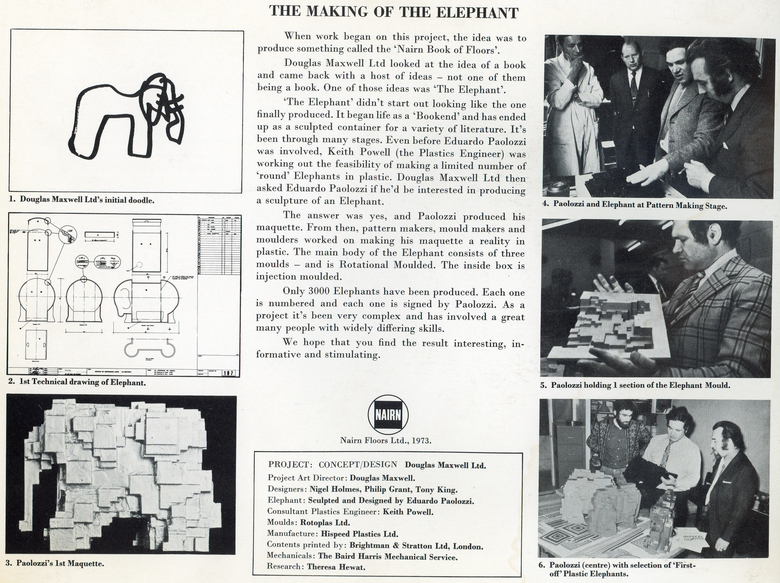

As our Paolozzi elephants return to our museum stores, we take a closer look at these plastic pachyderms.

Picture the scene. Its 1970, and you’re a Scottish floorcovering manufacturer looking for a way to display brochures at tradeshows and in showrooms. It needs to be tidy, eye-catching, and chic enough to capture attention of potential customers. Obviously, the answer is to commission one of Scotland’s most influential artists to create you a series of 3000 elephant-shaped boxes.

Sounds like a leap, but that’s exactly what happened. At the time of the commission, Nairn Floors were in a strange position. They had survived the tumultuous decade of the 1960s, remaining a player in an industry that had changed dramatically. Between 1963 and 1970, a vast number of linoleum factories in Kirkcaldy had been demolished, and Nairn’s was now the only firm making floorcoverings in the town.

They had also diversified into vinyl floors, and would try their hand at carpet. As they began to diversify, they looked to consolidate their position by advertising their products to architects. These were coveted clients as, if they specified a certain brand or style of floorcovering for a large project, Nairn’s could guarantee bigger sales than they could secure with customers looking to floor individual homes. There was also the possibility that architects might come back time and time again, whereas domestic sales were – by the nature of linoleum’s long life-span – less likely to garner regular repeat purchases.

Initially, the company approached a design company called Douglas Maxwell Limited, with the idea to produce a volume called the ‘Nairn Book of Floors’. The company took the brief, and came back with several ideas – one of which was not a book at all, but an elephant. The idea was that the elephant would act as an attractive ‘bookcover’ but that the pages kept inside it could be updated as products changed.

Seems logical enough – but why an elephant? We’re a bit unclear on how that happened. Was it due to the elephantine pressure linoleum could withstand through a stiletto heel? Or perhaps the longevity of linoleums lifespan put some in mind of mammoth memories? The answer is most likely a mix of the two, supported by a universal truth: everyone likes elephants.

Each elephant was accompanied by a booklet explaining the design process, with Paolozzi’s signature unmissable on the front cover.

At the time, Eduardo Paolozzi was already a big name in the art world. Born in Leith in 1924, Paolozzi is considered by some to have provided a name to the era-defining Pop art movement, by including the word ‘Pop!’ in his 1947 collage If I Was A Rich Man’s Plaything. By 1972, he could boast one-man shows at MoMA, the Tate and the Scottish National Gallery (which now holds his full archive). Obviously, the next logical step was to make an elephant for Nairn’s. It seems a strange move, but of the project Paolozzi said:

“The object was exciting to me as a sculptor. In one sense, what could be more organic than an Elephant? (Or the idea of an Elephant?). To interpret this into completely non-organic shapes, practically all geometric elements, with an emphasis on the horizontal and vertical planes, was a fascinating problem. […] I was aware beforehand of the various technical processes the sculpture would have to undergo, but found that many of the craftsmen involved were using a technology of a very fine kind, and this opened an entirely new world to me.”

The elephants – while strange and unusual to us – were inspiring to Paolozzi. They introduced him to new techniques which he would later use in his own work – most notably the Cleish Castle Ceiling.

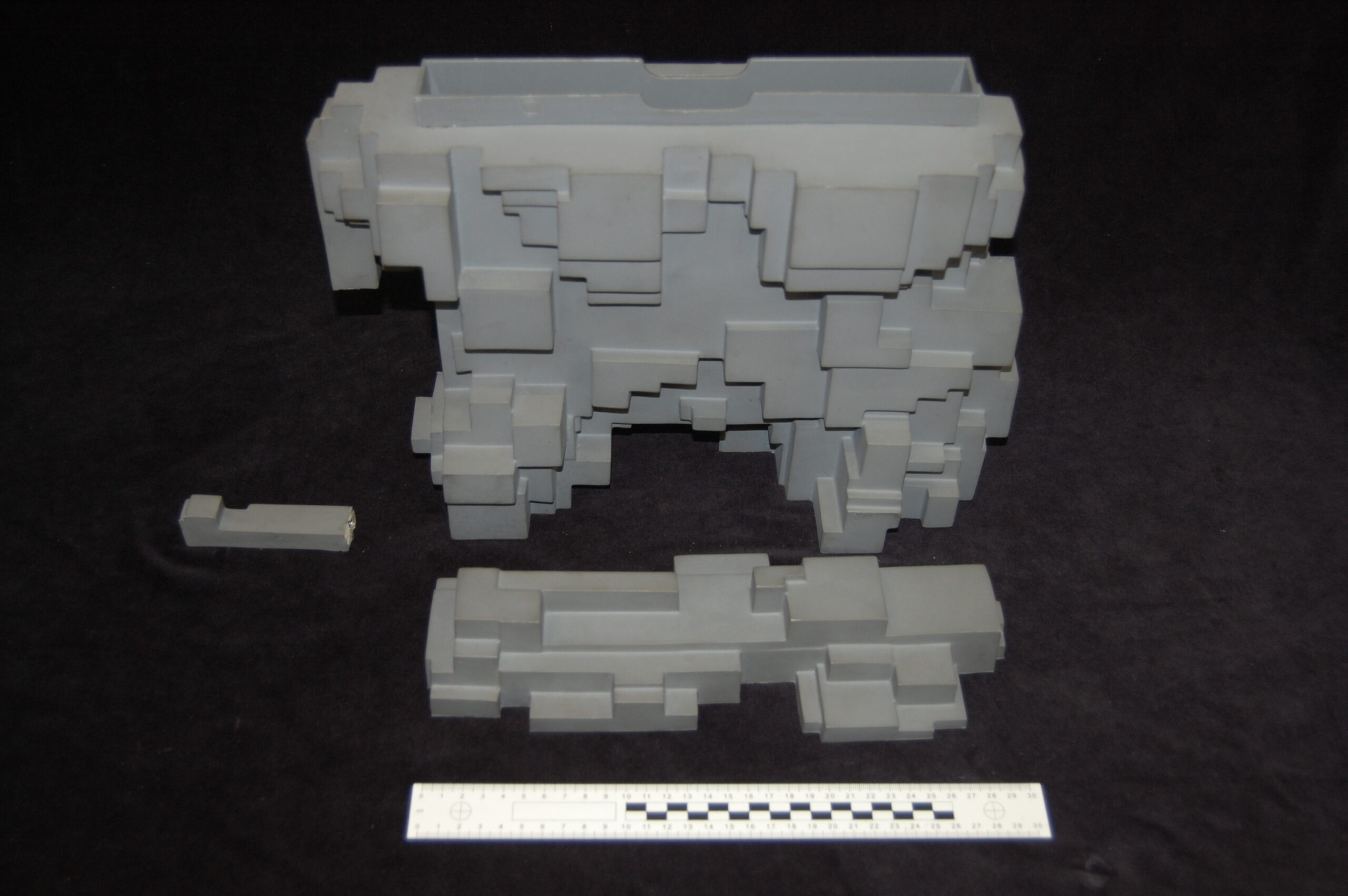

To create the elephants, he began by producing a maquette – or model – which ‘pattern makers, mould makers and moulders’ developed into a final design. Each elephant was accompanied by a booklet which detailed the process, in which it is modestly described as “very complex”.

3000 elephants were made and, though they occasionally pop up for sale in auction houses, today only a few are accounted for. There is one in the Metropolitan Museum in New York, one in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London – and two are held by us in our Collections Store at Bankhead, Glenrothes.

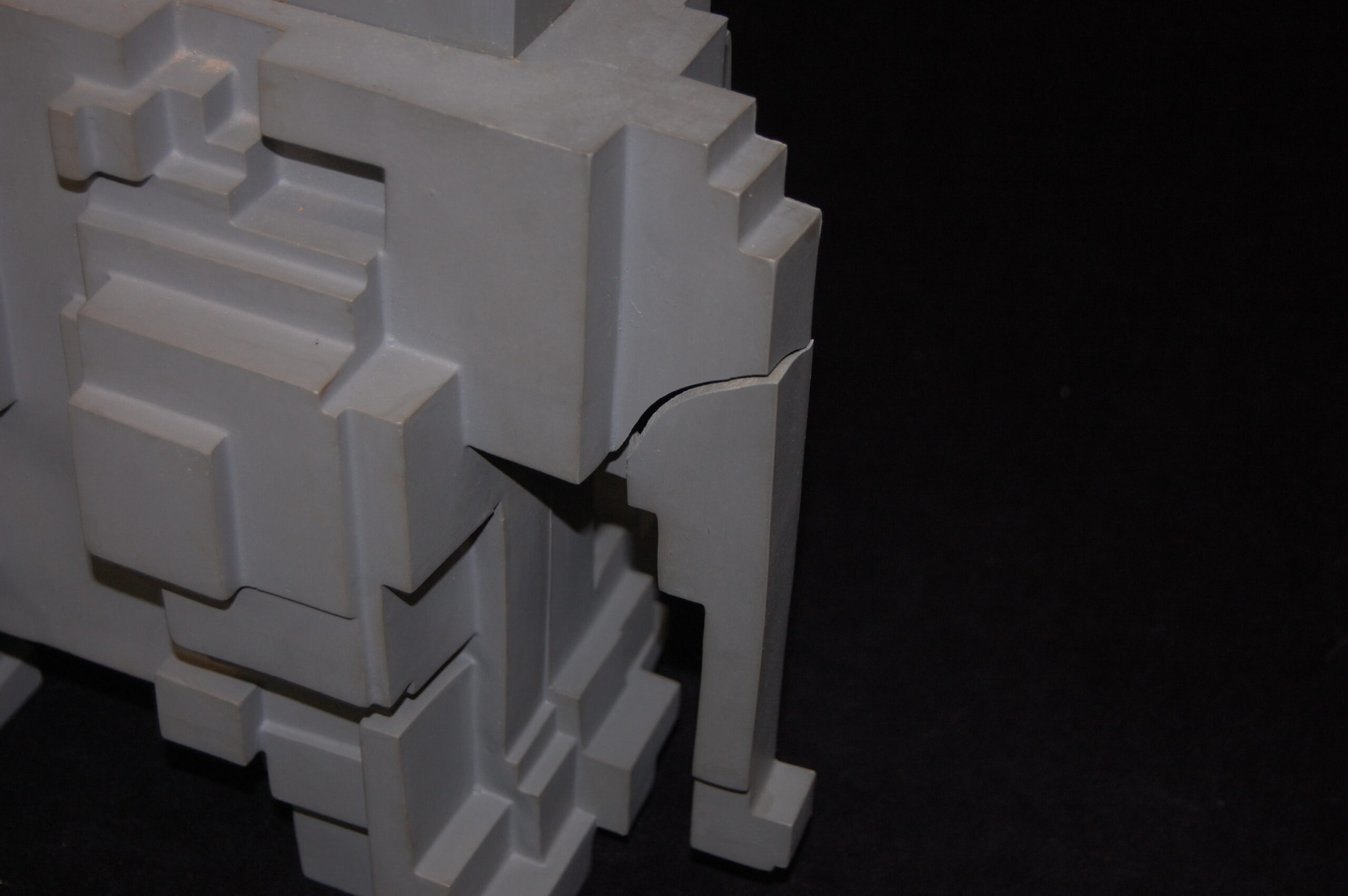

The first – marked number 768/3000 – had been with us for some time, and over the course of its life had lost its trunk. The second joined our collections this year. This one is not numbered, which may hint at it being a production proof outside of the run of 3000, perhaps produced especially for Nairn’s to keep – waiting in the archive until Nairn’s became Forbo, and Forbo chose to donate their archive to OnFife. This one had fared slightly better, but still had a few cracks across its surface.

Number 768, before conservation. KIRMG:1986.0300

While we’re all aware of the devastating environmental impact of plastic, many people are not aware of how difficult it is to preserve and care for. As it ages – which can be exacerbated by light or heat – plastic begins to deteriorate. This deterioration manifests in different ways, depending on the type of plastic; some become brittle and crack, some flake apart, some appear to melt, and most of these processes produce gasses which can damage other objects around them. On top of this, it is very difficult to tell the hundreds of different types of plastics apart. This makes care and preservation even more difficult; if we do not know what we are dealing with, we cannot tailor our behaviour to best suit its needs.

The unnumbered elephant from the Forbo Archive, with a few cracks across its surface. FIFER:2022.0235

This proved to be an issue when it came to the elephants. It was impossible to identify which kind of plastic they were made out of and, as such, the conservator could not predict how they might behave in future. Ultimately, this led to us deciding to only conserve one of them – 768. While this elephant’s trunk could be repaired using a dowel, the cracks on our unnumbered elephant would require adhesive, which could cause further damage in future if the plastic were to expand or contract. To protect both as much as possible, we opted for different treatments. Together, the pair make a perfect ‘before’ and ‘after’.

Number 768 after conservation, re-trunked and ready to go!

Our original elephant wasn’t included in the Queer-Like Smell exhibition in 1992, so the pair have yet to make their debut appearance at one of our venues. Until now! You can find the elephants at Kirkcaldy Galleries from 16 December 2022 – 8 March 2023.

Flooring the World is a two-year project exploring the history of the Fife linoleum industry. It is funded by the Esmée Fairbairn Collections Fund, which is run by the Museums Association.

As part of the Flooring the World project, we are looking to actively improve our linoleum collections. This means rehousing the objects we already have, conserving those which need a bit of TLC, and researching those we know less about. It also means welcoming new objects into the collection and, to celebrate Scottish Archaeology Month, we wanted to tell you all about a recent addition.

Resin. FIFER.2022.0639

This lumpy orange stone was found on a beach on the shores of the Firth of Forth by a schoolboy in the 1970s, who initially thought it was a piece of amber. It was sent to the National Museum of Scotland, who told them that – instead – it was actually a large piece of resin.

Now, this is where the archaeology comes in. A lot of us, when we think of archaeology, imagine trenches dug in fields or roads, with lots of hat-wearing, hard-working people toiling through the mud to find Roman coins, Celtic bones, or – more usually, as several archaeologists have told me – more mud, and maybe the odd chicken bone.

In fact, this is just one type of archaeology. But, archaeological material can be discovered in lots of different ways. Artefacts can also be revealed by chance; washed up on beaches and river-banks, or exposed by storms of flooding damaging the landscape.

When we find something in this way, the challenge is then to work out how it came to be where it is. Did it enter the water way, and then get moved by currents to where you found it? Or was it buried (by accident or on purpose) and then exposed by erosion? And, then, a second question: how old is it? Has it been making its way to the beach for centuries, millennia, or just days?

These questions are more difficult to answer on the tideline than on dry land. If an object or site has been exposed by extreme weather, archaeologists may only have a short amount of time to carry out their investigations before the area is further damaged or completely destroyed. Finds will have to be quickly catalogued and removed, as any clues left unnoticed will be washed away. This was the case with the Lundin Links burial ground, which was exposed by storms shortly before our resin was found (which you can learn more about here).

Alternatively, if an object is washed up on a shoreline then we have no clues from its surroundings to tell us more about it. When removing something from the ground the depth at which is it buried, what is above and below it, and where it is all tell us something about it. This is called its archaeological ‘context’. If we don’t have this, we have to get more creative, and look at the object itself.

So, to start with, what is resin? Resins are viscous liquids which are secreted by plants when they are damaged to protect them from pests and disease. The thing that we call ‘amber’ – which the schoolboy who found our resin thought they had stumbled across – is prehistoric resin which has become fossilised and turned into stone. It starts life as resin and – as Jurassic Park taught us all – ends up decorating the canes of eccentric millionaires who use the mosquitos trapped within to unravel the genetic codes of extinct megafauna.

But, if that doesn’t happen, resin can be a useful raw material in a number of different industries. If you’ve ever played a violin, viola or cello, you’ll have used a resin to prepare your bow. If you’ve ever been second in line to offer a gift to Jesus Christ, you’ll have opted for a resin known as frankincense. And, if you’ve ever made linoleum, you’ll have used resin to create the thick, waterproof substance which makes up the surface of the Fife’s favourite floorcovering.

This sample case contains different materials used to make linoleum, including resin, fifth from the left. KIRMG.2007.564.1-17

This, we think, is how our piece of resin ended up Forthside. During the 1960s, the Fife linoleum industry suffered several losses. Perhaps most significant was the decision of Barry, Ostlere and Shepherd – Kirkcaldy’s second oldest and second largest linoleum manufacturer – to cease all production of the floorcovering in the town, relocating production to Staines, Middlesex.

This change had an enormous impact on the shape of Kirkcaldy. Up until the end of the 1960s, the town had been dominated by linoleum factories – generating the ‘queer-like smell’ which they town became famous for. In particular, the area around Kirkcaldy galleries was filled with Barry’s buildings.

Newspaper cutting from the Local Studies collection at Kirkcaldy Galleries.

Between 1969 and 1970, all of these buildings were demolished. In addition, several buildings belonging to Nairn’s linoleum firm – including the original ‘Nairn’s Folly’ floorcloth factory – were also destroyed. The rubble and waste material generated by the demolition was deposited at Pathhead, to ‘build up the beach’. With so much linoleum related material so near to the beach, we suspect that this may have been when our resin entered the river Forth, turning up on the shoreline not long afterwards.

You can see this object – and learn more about the linoleum industry in the 1960s – in a temporary display in the Moments In Time Gallery, Kirkcaldy Galleries until 27 October 2022. You can also check out our blog post about the display here.

_________

This blog was written by Lily Barnes, curator working on the linoleum project Flooring the World (2022-2024). Flooring the World is a two-year project exploring the history of the Fife linoleum industry. It is funded by the Esmée Fairbairn Collections Fund, which is run by the Museums Association, funding projects that develop collections to achieve social impact.

The 1960s was a decade of immense change for Kirkcaldy. Change – and not just the smell of linseed oil – was in the air. Linoleum manufacturers were innovating, creating new products and fashionable designs for new and exciting times.

However, the decade also saw the beginnings of sharp decline of linoleum production in Britain. The future of the Fife industry – and the thousands of people who depended on it for work – began to look increasingly bleak.

We’ve just installed a new temporary display in our Moments In Time gallery (on display until 27 October 2022), exploring some of these changes using objects and photographs from our collections.

While creating the display, we’ve been thinking about what it would have been like to live in Kirkcaldy during this uncertain time. As the fortunes of the linoleum industry began to shift, what did people feel, what did they see – and what music did they listen to?

Why music? Have you ever been going about your life, and heard a song – in a shop, on the TV, on the radio – and been instantly transported to another time when you heard, sang or danced to that song? Last week I was in a pub where a Red Hot Chili Peppers song was playing, and immediately remembered driving in the car with my dad, singing to the same song and holding my hand out of the open window. Something like this has probably happened to you too.

With music from times and places which we didn’t experience, music can have a slightly different effect. It’s easy to forget that people in the past – whether it’s the 1960s or the 1560s – were essentially the same as we are now. They had the same thoughts, feelings, likes and dislikes. Listening to music from those times, regardless of whether we know the songs, help us to remember that, and to better understand our history.

Newspaper cutting from the Local Studies collection at Kirkcaldy Galleries.

So, we created this playlist as a bit of an experiment: to help those of you who were in Kirkcaldy during the 1960s remember the time more clearly, and to help those of us who weren’t to imagine what it might have been like. If you have a Spotify account, you can listen here. If not, click here to listen on Youtube. Without further ado, here it is:

1. (If I Say I Love You) Do You Mind? – Anthony Newley

2. Walking Back to Happiness – Helen Schapiro

3. Moon River – Danny Williams

The first three songs on the playlist were all hits in the UK between January 1960 and December 1961 – we picked them to correspond to the three samples of linoleum in the display. These songs don’t mirror the psychedelic influences in the linoleum designs, but they do represent a world on the cusp of a huge change. The new genres and styles of music which would become popular in the next few years – namely rock and roll – would come to dominate more traditional pop music.

4. Lovesick Blues – Frank Ifield

But, before we embrace change wholeheartedly, let’s indulge in a little yodelling. This song – made famous by Hank Williams in 1952 (and then again by Mason Ramsey AKA ‘the yodelling kid’ in 2018) was a hit in 1962, when customers from Kirkcaldy to Kings Lynn were covering their floors with designs from this pattern book. While it’s still a quite traditional ditty, we liked the imagining happy lino owners square dancing on their newly laid kitchen floors (and thought you might like to imagine it too).

This song was playing across the UK in 1963, and was at its most popular at the time the news of the Barry’s redundancies was announced in the Fife Free Press in April. It’s a very upbeat tune, and we were sort of hoping for something more in-keeping with the sadness many people in Kirkcaldy would have felt. Ultimately though, we decided to keep it in – it’s important to remember that the rest of the world doesn’t automatically follow suit during dark times.

6. From Me To You – The Beatles

Finally, the Beatles. This playlist would have been empty without them, as the band have quite a few connections to Kirkcaldy, and to our linoleum collection. This song would have been heard across Kirkcaldy the day of the Barry’s march in May 1963, and the band would play a show at the Carlton Cinema on Park Road just months later.

7. She’s Not You – Elvis Presley

Though we tended towards British artists when making our selections, we’d have been remiss if we didn’t include a bit of Elvis. As one of the most iconic voices of the decade, we were sure that people in Kirkcaldy must have been singing this song as events unfolded. This song was a hit when Nairn’s announced that they would be merging with rival firm Williamson’s in September 1962, a move which was finalised in the winter of 1963.

Like other Kirkcaldy firms, Nairn’s was forced to downsize, diversify and consolidate its business during the 1960s. The decision to merge with Williamson’s, however, may have been what saved it from a full closure; unlike Barry’s, its Kirkcaldy production survived the decade.

Newspaper cutting from the Local Studies collection at Kirkcaldy Galleries.

8. Where Do You Go To – Peter Sarstedt

From 1969, linoleum factories began to disappear from Kirkcaldy en-masse. The Barry’s factory complex, which had been mainly concentrated around the train station – was demolished in 1969. This completely changed the shape of the town; the queer like smell that had announced the town to visitors arriving on the rails for a hundred years was beginning to fade as the buildings were levelled. The area today is unrecognisable.

Not long after, the Nairn’s Pathhead complex suffered the same fate. This included the original ‘Nairn’s Folly’ building – a relic of the beginning of the floorcovering industry in Kirkcaldy. For residents of the town, this must have seemed a particularly bad omen.

This song was a hit earlier in the year, but we felt its melancholy, nostalgic tone seemed to fit well with the way the demolition of the Kirkcaldy linoleum factories made us feel – and perhaps made those in the town at the time feel, too.

This the first time we’ve used music to supplement our displays, and we’d love to know what you think. If this has prompted any thoughts or memories, or if you have any feedback you would like to share, you can e-mail Lily (Flooring The World Engagement Curator) at lino@onfife.com

_________

This blog was written by Lily Barnes, curator working on the linoleum project Flooring the World (2022-2024). Flooring the World is a two-year project exploring the history of the Fife linoleum industry. It is funded by the Esmée Fairbairn Collections Fund, which is run by the Museums Association, funding projects that develop collections to achieve social impact.

Image: A pattern book. KIRMG:1992.0267

This is a pattern book, produced by Nairn’s of Kirkcaldy in 1930. It contains full-colour images of the linoleum designs produced by the company in that year, and would have been made available for customers to browse before they made their selection.

We have over fifty of these in our collections, dating from the mid 19th century to the 1960s. As we continue to accession the Forbo Factory archive, modern brochures join this collection to allow us to view linoleum as potential customers have for 150 years. While the way in which linoleum is made has changed little in that time, the styles sought after by and available to customers have changed dramatically.

20th and 21st century designs tend to be more general in their function; today, Forbo brochures showcase marbled-pattern linoleums in a kaleidoscope of colours, fit for every style and season.

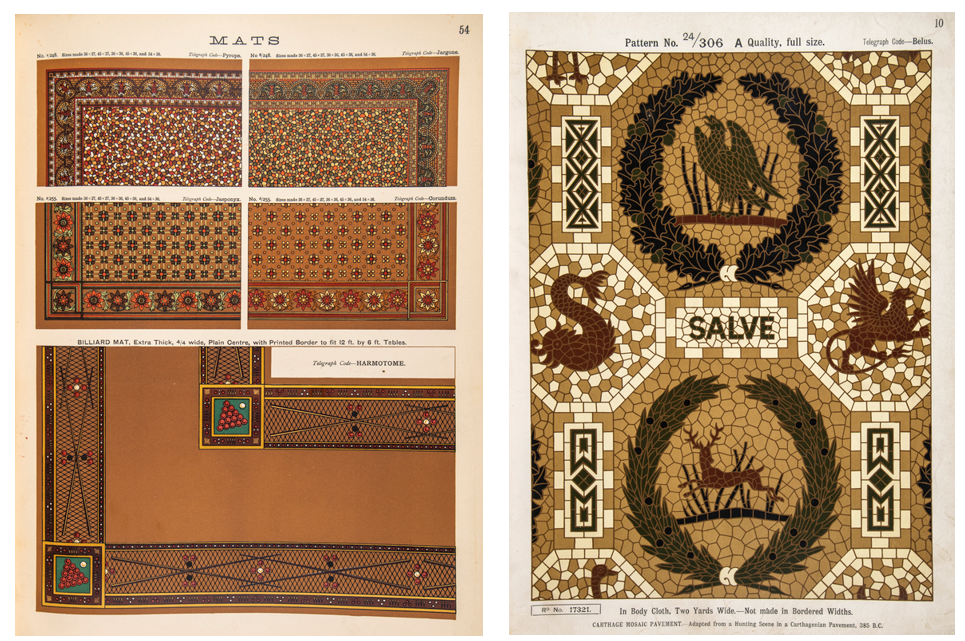

However, our 19th century pattern books contain designs created with specific spaces in mind. One features a border of cues and billiard balls for a games room, and the inclusion of the word ‘Salve’ (the Latin for ‘welcome’) in this classical design points towards its being intended for an entrance hall. The room in the house which seems to have generated the most elaborate space-specific designs, however, is the nursery.

Images: Two pages from FIFER:2022.0150.

Today, we associate linoleum in the home mainly with kitchens and bathrooms; in the 19th and early 20th centuries, it (along with its forerunner floorcloth) could be found in any room. So, with all these rooms to choose from, why designs intended specifically for the nursery? This trend was dependent on two key social developments in the late Victorian period. The first, as strange as it sounds, was the invention of childhood.

Prior to this time, the common consensus was that there was nothing special about being a child. Children wore miniature versions of adults’ clothes and contributed economically to the family by working. They were seen as miniature versions of the grown-ups they would become – with any variations from adulthood being seen as passing nuisances.

In the mid 19th century however, improving economic conditions and the rise of the middle-classes meant that it was not always essential for children to work to support a household. Life before adulthood became associated with leisure, play, and innocence. Rather than a temporary state of smallness, childhood became something to be cherished and protected.

Image: Portrait of Ian Couper Nairn, by Harrington Mann. KIRMG:383. The children of the Nairn family – Kirkcaldy’s original linoleum manufacturers – had their portraits painted in 1899. They would’ve been among the first generations of children raised according to new notions of childhood. In this portrait, we see Ian Couper Nairn standing in an interior – perhaps a glimpse into his linoleum floored nursery?

This same economic improvement brings us to the second change: a greater separation between work and the home.

Due to British imperialism, this period was marked by accelerated industrialisation. As the shape of work changed, so too did the shape of the workplace. Towns and cities across the country became filled with factories and warehouses – transforming raw materials and storing finished goods extracted from overseas territories – and offices to manage these global businesses. Britain grew rich by travelling beyond its shores, exploiting the people and lands of its acquired territories. As a result of this, middle-class families were able to mirror this expansionist impulse, travelling beyond their homes to new, modern workspaces.

On a practical level, this meant that many middle-class Briton’s now found themselves with more space in their houses. So, as childhood became a precious, protected time in a person’s life, the home became a special place reserved for leisure, relaxation and the family (though each of these privileges was dependent on being born into a family wealthy and stable enough to afford them). The extra space in the home therefore naturally became a place exclusively reserved for children: the nursery.

This meant that there was suddenly a new market to be catered to. However, the idea that children will have at least some say in how their spaces are decorated is a relatively new one. So – while children would undoubtedly have enjoyed them – these patterns were primarily designed to cater to the adults who would be purchasing them.

More specifically, they appealed to women. Though men’s work had left the home, women’s labour remained. As the home began to change shape (and size) in response to these social and economic changes, a new task emerged for the middle-class Victorian – the creation and cultivation of a tasteful interior.

Whereas once, home furnishings beyond the functional and comfortable were the preserve of the upper-classes, middle-class homes were now also expected to be finished in the latest fashion. From the 1860s, ‘homemaking’ became a respectable pastime for well-to-do women, joining the ranks of other sanctioned hobbies such as album-making, crafting faux flowers, and fern collecting. Each of these hobbies was seen as distinctly feminine, and as exercises by which women could cultivate their finest ‘womanly’ traits and, by extension, their morality. They required quiet, rewarded perfectionism and patience, and encouraged the contemplation of the meek and delicate.

Homemaking fulfilled a similar function, but with a crucial difference. Whereas these other crafts resulted in small, hidable products, home décor was a comparatively public medium for self-expression – or, more accurately then as today, an expression of the self one wished to impress on others. An ill-pasted page in an album could be avoided; an unkempt, poorly appointed room was for all to see.

Alongside creating a home which was fashionable and comfortable, therefore, the middle-class Victorian woman also had to make sure her home décor choices conveyed her unblemished character. This meant, of course, that it had to be clean.

In the 19th century cleanliness was truly next to godliness; any evidence of dirt or wear was surely a sign of loose character. Here then, the Victorian woman was in a bind. To be a ‘good’ wife, it was expected (perhaps even necessitated in an era with paltry access to contraception) that she have children. However, that goodness would be easily undermined by mess which naturally accompanied those children. The solution to this problem was – you guessed it – linoleum.

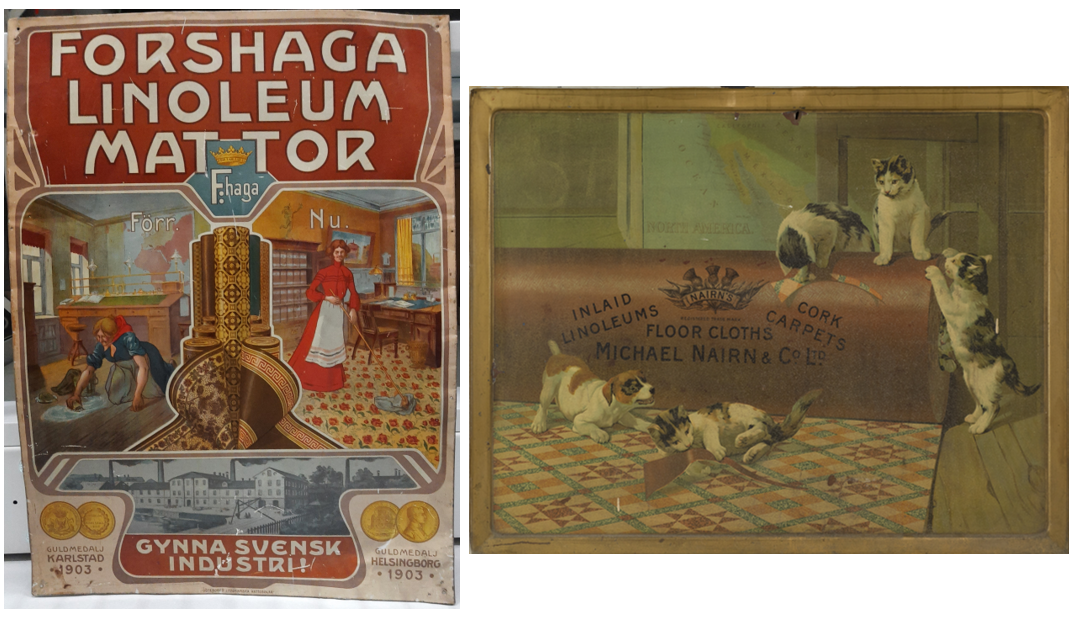

Images: This advert for Forshaga linoleum (left; FIFER:2022.0201) touts the floorcoverings virtues in relation to the body of the housewife. In Kirkcaldy (right, TEMP:2011.4263), a slightly different tactic was used to emphasise linoleum as a labour-saving innovation. This advert by Nairn’s impresses that its products are dry-wipe using the cute metaphor of puppies and kittens rather than the unpleasant reality of the messes all young animals – including nursery-bound humans – make.

The hygienic qualities of linoleum have always been central to its appeal, and the same was true in the 19th century. Linoleum was quicker and easier to clean than traditional floorcoverings, and this was exploited in adverts, such as this one produced by Swedish manufacturers Forshaga.

The stress of cleaning a wooden floor is obvious in the face of the woman scrubbing them who – with her muscular arms and messy hair – is coded as working-class. The leisured middle-class homemaker on the right does not have to spoil her appearance or her delicate, idealised figure with such labour: she has linoleum. Linoleum, therefore, was a good and proper thing for Victorian women – indeed, it would help them preserve their status by ensuring that their homes and bodies conformed to class and gender norms.

If dirt and mess was a visual sign of moral decay, noise of any kind warned the ear of bad character. Here too, linoleum had the edge over wooden, stone or tiled floors. Linoleum – particularly thicker and more expensive varieties such as cork carpet – muffled the sounds of toys bounced, dragged or skittered across it (while also resisting any marks they might make). It was also more forgiving on toddling, crawling bodies – which (theoretically) meant less crying. Childhood was precious – but children were still meant to be seen and not heard.

Once a Victorian woman was certain she had a clean and moral home, she had to turn her mind to the future – and that meant education. It was up to her to impress both knowledge and upright values on her young charges – and linoleum – it was hoped – would shape the futures of the small humans who walked on it.

Image: This cork carpet design, dating from 1892, shows children playing in an imagined countryside. At a time when the industrialisation which made floorcoverings like these and the nurseries which housed them possible, there was a strong popular taste for images of a rural life which was imagined as simpler and more innocent than modern cities – just as childhood became seen as simpler and more innocent than adulthood. FIFER:2022.0174

The floorcoverings designed for nurseries served as teaching tools as well as decoration. Writer Samuel Smiles stressed the importance of visible examples of good behaviour, insisting that these were far more impactful than mere explanation. More was at stake than just a peaceful homelife; for Smiles, “the nation [came] from the nursery” – the health and strength of the country depended on children knowing clearly what was expected of them.

To do this, floorcovering designs borrowed heavily from other media created with children in mind. Illustrated books produced by English artists Kate Greenaway and Walter Crane clearly had a strong influence on the designs in our collections.

The design above clearly mimics Greenaway’s style. It epitomises the idealised childhood of the time – well-behaved, flaxen-haired children frolic unsupervised in a colourful, pastoral idyll. Their world is unblemished by signs of work or modernity; their play is neat and innocent. Children surrounded by these designs surely could not help but follow their example, as Smiles hoped.

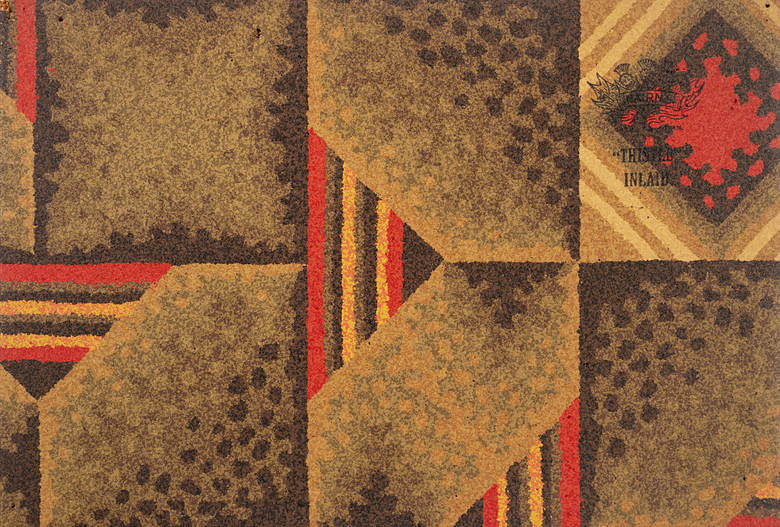

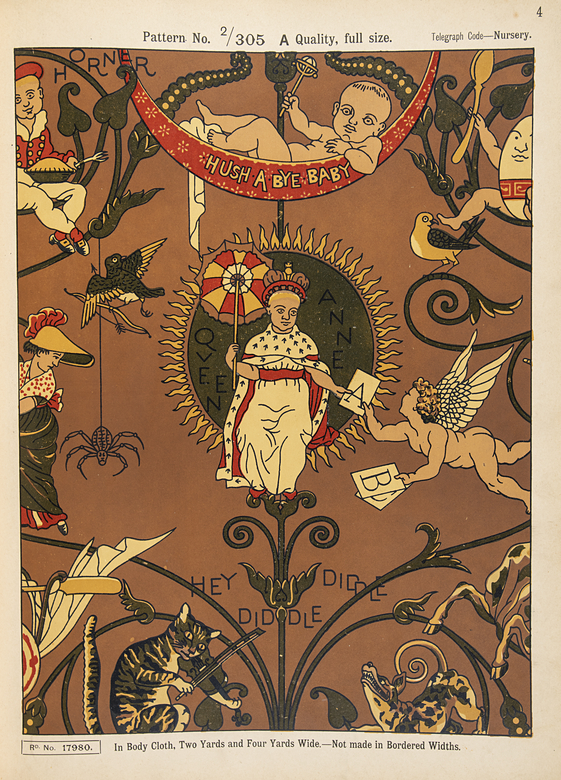

Image: In a pattern book produced by the Kirkcaldy Linoleum Company, 1876 – c.1900. Though the colours differ from Crane’s wallpaper, the rest of the design is identical. Though most of these nursery rhymes have stood the test of time, the central song ‘Letters to Queen Anne’ appears to have faded away from the nursery in the 20th century. FIFER:2022.0150

Another theme favoured by interior design writers, consumers and manufacturers alike was nursery rhymes. This design by Walter Crane was commissioned by Jeffrey and Co. in 1876; examples of this paper – both in a predominantly blue and yellow colour scheme – survive in the collections of the V&A and the Cooper Hewitt Museum. We don’t know exactly when it was adapted by the Kirkcaldy Linoleum Company, but the fact that it was is testament to its popularity.

Pictures in rooms used by children served the same purpose then as they do now: to provide bright and colourful memory aids to assist learning and lend rhythm to group games and activities. Children living in industrial cities might not venture into a Greenaway-esque countryside, but they would still learn to tell a cow from a spoon in a well-appointed Victorian nursery, as well as maybe learning a bit of the alphabet.