In the autumn of 1939, workers at Nairn’s floorcovering factories downed tools and marched through the streets of Kirkcaldy. Over the summer of 2023, Fraser Scott – a volunteer with the Flooring the World project – researched the strike, and its context in relation to labour rights in Scotland in the early 20th century.

The Nairn family was generally seen and thought of themselves as being “philanthropic” towards their employees. The firm had been involved in community projects since the late 19th century. In 1877, they funded of the construction of St Brycedale church, and in 1894 Michael Barker Nairn funded the renovation and rebuilding of Kirkcaldy Burgh School. He also “established trust funds” for medals, prizes and university bursaries to further support the school’s pupils.

A view of Kirk Wynd. The steeple of St Brycedale Church is visible to the right.

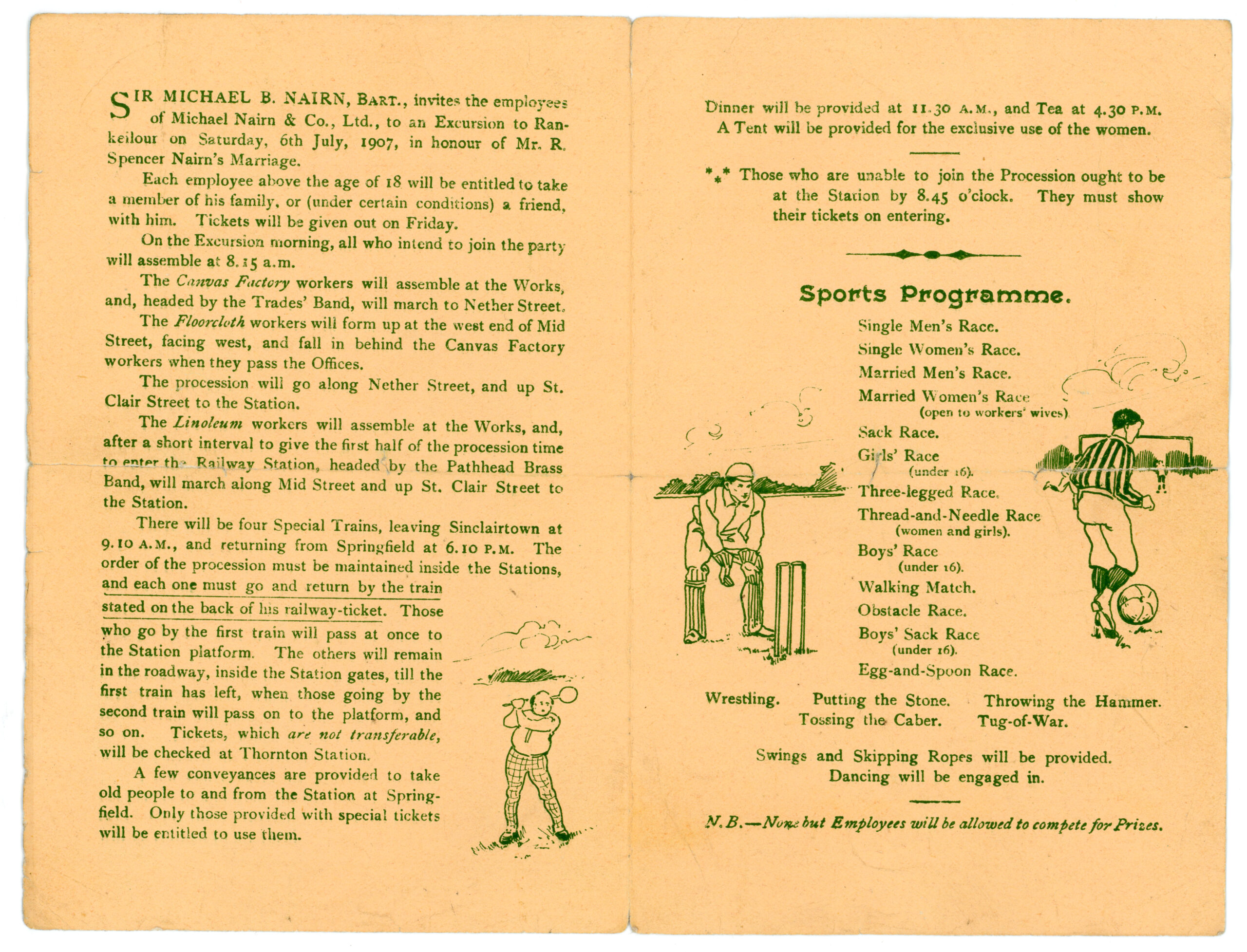

In their factories, Nairn’s extended this generosity to their employees. They organised events events – such as summer excursions to the family estate at Rankeilour, Cupar – and amenities such as cinemas, sports facilities. When it came to wages, Nairn’s employees were given a yearly bonus and, most notably, during WWI the company provided payments to the families of the six hundred workers who had joined the armed services.

However, this philanthropy doesn’t hide the underlying labour tensions between Nairn’s and their employees. In an oral history interview in OnFife’s collections David Lawson, who was employed at Nairn’s in 1939, points to the general hostility that Nairn’s had towards unions and dissenting workers. Describing an occasion when he and other union members met with Nairn’s officials, he remembered: “[They said] you men, you should realise we have done a lot for Kirkcaldy”. The implication to Lawson, was that the philanthropy of both firm and family was seen as a moral excuse to justify intimidating their workers into not organising.

Along with this, Lawson noted that the company were quick to hand out penalties. The yearly bonus would be withdrawn “automatically” if a worker was late. The same applied for striking. Lawson notes that he was among a group of workers fired en masse for organising:

“I missed the first fifty, the next week another fifty fired and my name was on the list”.

This indicates that, even before the 1939 strike, Nairn’s attitudes towards unions and strike action was generally hostile and draconian. To some, this indicated that their philanthropic policies had a dual purpose: to discredit the unions by showing that Nairn’s had a concern for their workforce, and to discourage the workers themselves from organising against them.

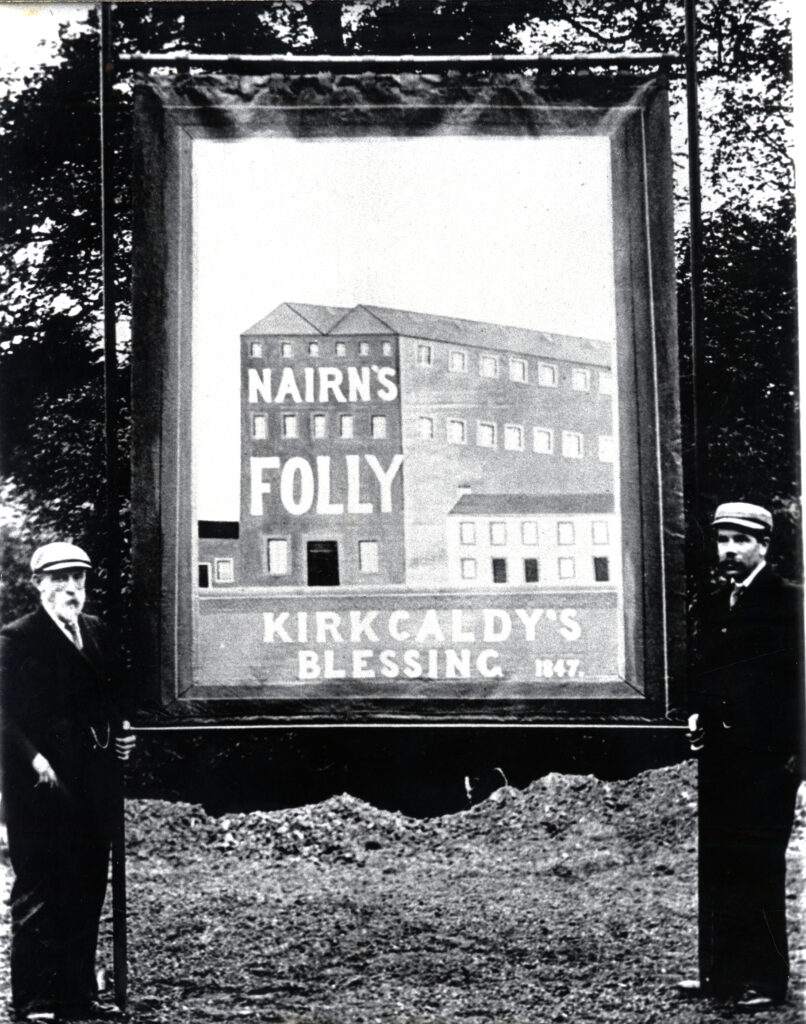

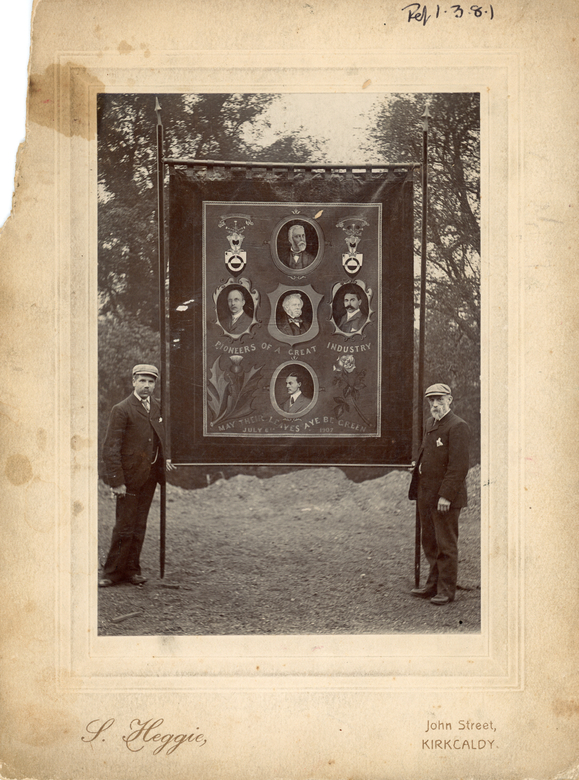

In promoting their charitable works, Nairn’s presented themselves as ‘Kirkcaldy’s Blessing’. This floorcloth banner was carried by workers in their annual processions c.1900 – 1909.

Striking in Scotland

The Nairn’s strike can be seen in the context of other examples of industrial action in Scotland. During the early 20th century there were several upheavals in labour relations at the time, most notably ‘Red Clydeside’ and the General Strike.

Red Clydeside occurred in the immediate aftermath of WWI. Already rising tensions over poor pay and high rent in Glasgow (the cause of the 1915 rent strikes) mixed with the lack of opportunities for returning soldiers gave ample opportunities for union activists to organise and agitate. As such in January 1919 the CWC (Clydeside Workers Committee) organised a mass demonstration in George Square involving up to 25,000 with inevitable clashes resulting in 36 injuries.

The Red Clydeside events of 1919 were important in the Scottish context, as labour organisers would rise to national prominence and even be elected to office. Organiser Willie Gallacher was later elected as an MP for West Fife. Socialist organisations were also propelled by Red Clydeside. The Labour party, having demonstrated their solidarity with workers, secured massive gains in Glasgow and other industrial areas in Scotland

Following this, the 1926 General Strike also provided a precedent for industrial action across the UK. The strike was largely caused by the changing prospects of the British coal mining industry. During WWI, overseas sources of coal from Germany and France had been cut off. This meant that increasing demand was placed on mines in the British Isles, with workers wages rising alongside it. The end of the war meant that this period of prosperity for coal miners came to an end. Already working long hours in dangerous and dirty conditions, miners were now faced with a dramatic drop (almost half, in some cases) in their pay/

This – coupled with significant inflation which impacted workers and businesses across the country – led the Trade Unions Congress (TUC) to call for a general strike of all workers. From the 4th May, at least 1.5 million workers ‘from Land’s End to John O’ Groats’ refused to work.

Despite the impressive turn out, in terms of gains for the British labour movement and trade unions the strike was a disaster. In response, the British government amended the 1906 trade relations act to stop unions from striking together and to prevent mass picketing outside workplaces.

The Nairn’s Strike

The strikers passing Nairn’s head offices at Braehead House, Victoria Road.

By October 1939 the National Union of General and Municipal Workers (NUTW), had made several applications for official recognition from Nairn’s. The firm rejected these, claiming that workers were being “harassed” by union members. As evidence, they referred to workers who had complained about being approached by union representatives during work hours. In one example, a worker named George Anderson was said to have approached packer Ethel Stevenson “with a view to having her join the union”. Stevenson “had the impression that [Anderson] was forcing her do so.

In response to Nairn’s refusal, Kirkcaldy NUTW secretary John Kay insisted that the union to “not back down”. They agreed to take action, initially planning a sit-in at the factory beginning on the 9 October. However, in the preceding days Nairn’s fired seven workers in an attempt to intimidate would-be strikers. As such, the NUTW instead decided to march through the centre of Kirkcaldy.

This move was carefully calculated. On the one hand, it was a more deliberate – and public – show of strength than the planned sit in. Hundreds of residents across Kirkcaldy would see the strikers, causing reputational damage to the town’s beloved Nairn’s. On the other, marching through the town allowed workers to demonstrate against their employers legally; if they moved throughout the town, they would pass close by their workplaces, but not picket directly outside them.

The resulting march involved between 1500 to 2000 workers – about 90 percent of all Nairn factory employees. The strikers began near the floorcloth factory in Pathhead, before turning down Victoria Road. This lead them past the linoleum works, and the company’s head office at Braehead House. They then continued past what is now Kirkcaldy Galleries, and on to the Adam Smith Theatre.

The strikers outside the Adam Smith Theatre.

On the following day the strike had intensified, with the Motorman’s union joining with the NUTW. The Motorman refused to supply the linoleum industrial with oil, meaning that the workers who remained were unable to operate their machines. Production ground to a halt.

Such a work stoppage forced Nairn to enter into negotiations. In the interim, employees would return to work with the promise that they would not be “victimis[ed]” for striking. Between the 17th and 18th both sides laid out their demands. Nairn’s wanting to stop union activism from occurring, and to maintain control over assigning work. The NUTW wanted their union to be officially recognised and to guarantee scheduled meetings between representatives and the firm. On the 19th October, the Unions won out. Nairn’s agreed to recognise the NUTW, on condition that they did not promote union activity during work hours and that Nairn would be able to take in workers complaints and keep control of business management.

If you would like to learn more about the Fife linoleum industry, you can visit the Flooring the World exhibition at Kirkcaldy Galleries (15 November 2023 – 25 February 2024). Flooring the World is a two-year project exploring the history of the Fife linoleum industry. It is funded by the Esmée Fairbairn Collections Fund, which is run by the Museums Association.

This brilliant photograph below is part of a set of four in our linoleum collection, which document a strike from the worker’s point of view. It shows a group of men gathered around a hand-written sign, which reads: ‘9th day of strike. Morale excellent. We swear to fight till the end.’ Until recently, this was basically everything we knew about these images. As part of the Flooring the World project, we decided to do some research to find out more!

We knew that these photographs showed strikers at a French linoleum factory in the early twentieth century but were unsure exactly when and where they had been taken. We were also not sure how they were connected to our collections, but suspected that they were linked to one of Kirkcaldy’s two largest linoleum companies: Michael Nairn and Company, and Barry, Ostlere and Shepherd.

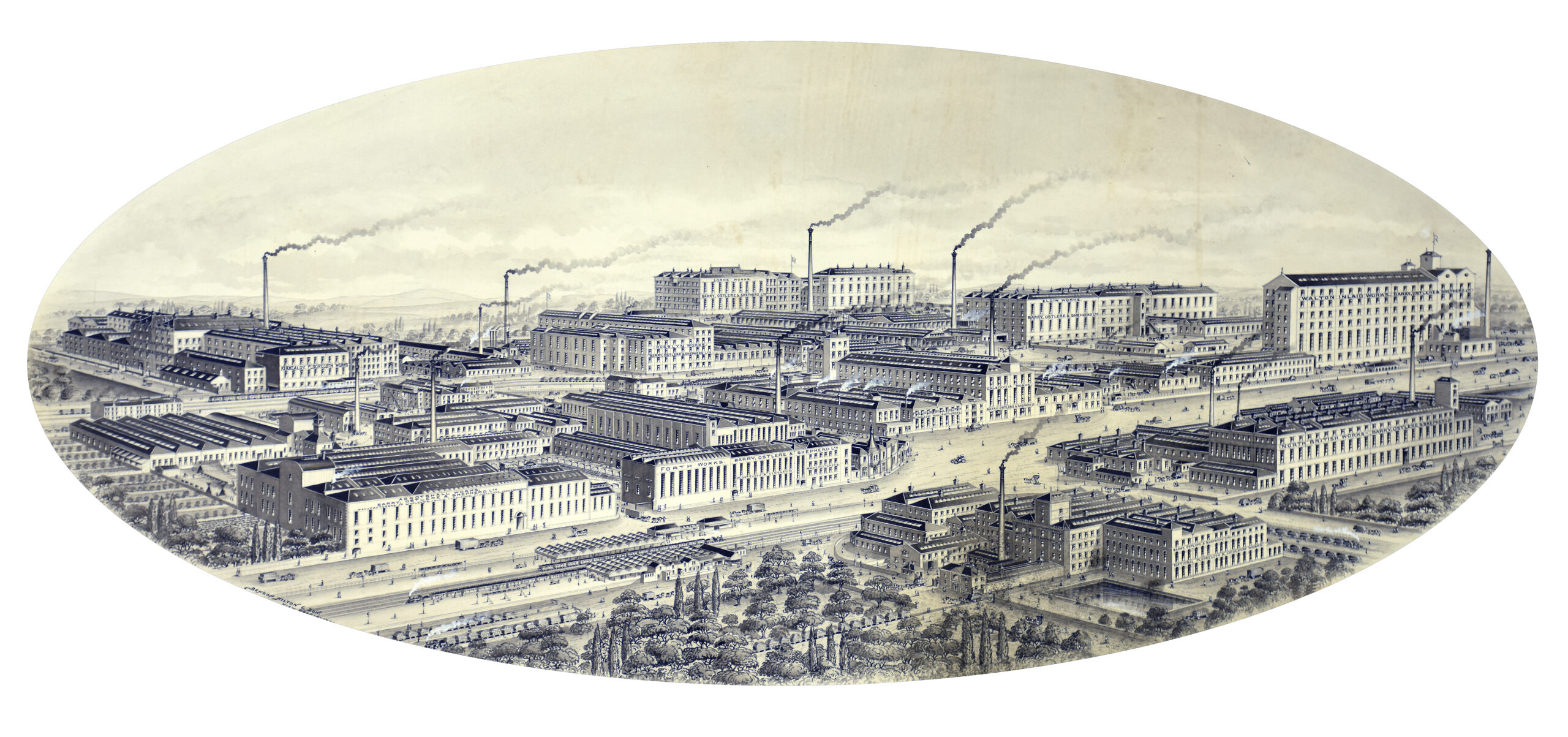

By the end of the nineteenth century, these companies had come to dominate the Fife (and by extension, the British) linoleum industry. Nairn’s was the town’s oldest firm, and had been growing its reputation since it started producing floorcloth in 1847. Barry’s was a relative newcomer, but – being formed from a merger between several of the town’s smaller firms – had effectively grown to a size where it could compete with Nairn’s by absorbing its own competition. Both firms operated multiple factories across the town: both had premises in Sinclairtown, while Nairn’s dominated the harbour and Victoria Road, and Barry’s surrounded Kirkcaldy’s central railway station.

This image shows all the factories operated by Barry, Ostlere and Shepherd in Kirkcaldy, 1905. The factories have been re-arranged to look as if they were all beside each other, but in reality were spread throughout the town.

Outside of Kirkcaldy, both Nairn’s and Barry’s also operated factories overseas, meaning that our strikers could have been employed in a French factory operated by either firm. In order to form a more certain link, and to learn more about our strikers, we’d have to look outside of our collections.

This photograph shows the in-house fire brigade employed at Nairn’s factory at Choisy-Le-Roi, France.

We began by searching Gallica, a database which allows you to search the collections of the French National Library (Bibliothèque National de France, or BnF). Initially, we limited the date range to 1900 – 1929. This was a rough estimate based on the clothes the men were wearing in the photographs; working class men’s fashion is very hard to date as it changes relatively little across a span of decades, but it can still sometimes provide you with an approximate idea. We then searched the database for the word ‘linoleum’ appearing in the same text as the word ‘grève’ (the French for strike).

This resulted in a few results! Sadly, most of these were newspapers or journals which featured adverts for linoleum alongside reports of strikes in other industries. While these were testament to the ubiquity of linoleum in the early 20th century, they did not necessarily help us to answer our strike questions!

Workers playing cards during the strike. The surnames and first initials of some of the strikers are written on the reverse of our prints. In future, it may be possible to learn more about them by using family history research skills.

However, one result did look promising. In an issue of L’Humanité – the official journal of the French Communist Party – dated to 7 March 1923, mentioned a strike at a linoleum factory in Le Houlme, Normandy, operated by La Compagnie Rouennaise de Linoleum. But what was the link between this strike, and our collections?

The answer lies in that busy time at the end of the 19th century when Nairn’s and Barry’s were consolidating their power. Barry, Ostlere and Shepherd was officially formed in 1899, by a merger between John Barry, Ostlere and Company, Shepherd and Beveridge, and the Kirkcaldy Linoleum Company – all of whom had been producing floorcoverings in the shadow of the older and more established Nairn’s. There was however a fourth company included in Barry’s DNA: a little Normandy venture called La Compagnie Rouennaise de Linoleum (CRdL).

The CRdL was established in 1897, two years before it became part of Barry’s. At the time of the merger, it employed approximately 150 people, which rose to around 500 by 1950. It is therefore likely that their workforce at the time of the strike was somewhere in the middle of this range. The image below shows 87 men gathered outside the factory gates, indicating that a significant proportion of the factory’s workers decided to take action against their employers.

2023 marks 100 years since the workers of Le Houlme went on strike!

The strikers’ demands were centred around their pay. Their employers had offered to increase their pay in the summer months, but not the winter, and this had been rejected. However, it is also possible that the connection with Fife may have added to the workers’ grievances. A report in our collection written in the 1950s by T J Cavanagh, one of Barry’s managers, noted that the French factory often had to make do with out-of-date equipment. When new machines were purchased, these were prioritised for Kirkcaldy who then sent their cast-offs to Normandy. It is possible that the feeling that the French factory was something of an after-thought may have been present in the 1920s, and contributed to the feeling of discontent among the workers.

We don’t know how long the strike went on for after the 11th day captured in the last photograph above. The next issue of L’Humanité reported that the Rouennaise strikers had been victorious – but this came just a few days after the original report of 7 March. This means it’s quite likely that it took a few days for the strikers to get in touch with L’Humanité – or perhaps they turned to the Communist party to increase pressure once the strike had gone on for longer than anticipated.

In either case, the workers were victorious! Their employers agreed to give them a pay rise of 175 cents per hour, holiday pay and to ‘keep all their pre-strike advantages’. This last is slightly ambiguous, though it was common for striking workers to request agreement in writing that they would not be prejudiced against for striking when they returned to work. It is possible that this clause was included to guarantee this kind of protection.

The CRdL continued to manufacture floorcoverings until 1968, some five years after Barry’s ceased production in Kirkcaldy (though the company survived until 1969 in Staines Middlesex, and until 1978 in Newburgh, Fife). Like many of Fife’s factories, it was fell victim to the falling demand for linoleum as alternative floorcoverings became cheaper to buy and easier to maintain.

_____________________________________________

Flooring the World is a two-year project exploring the history of the Fife linoleum industry. It is funded by the Esmée Fairbairn Collections Fund, which is run by the Museums Association.

![]()

Our linoleum collections consist of over 5,000 objects, documents and photographs, covering over 170 years of history. For this story, we’re heading all the way back into linoleum’s pre-history, to its origins in the Kirkcaldy floorcloth industry.

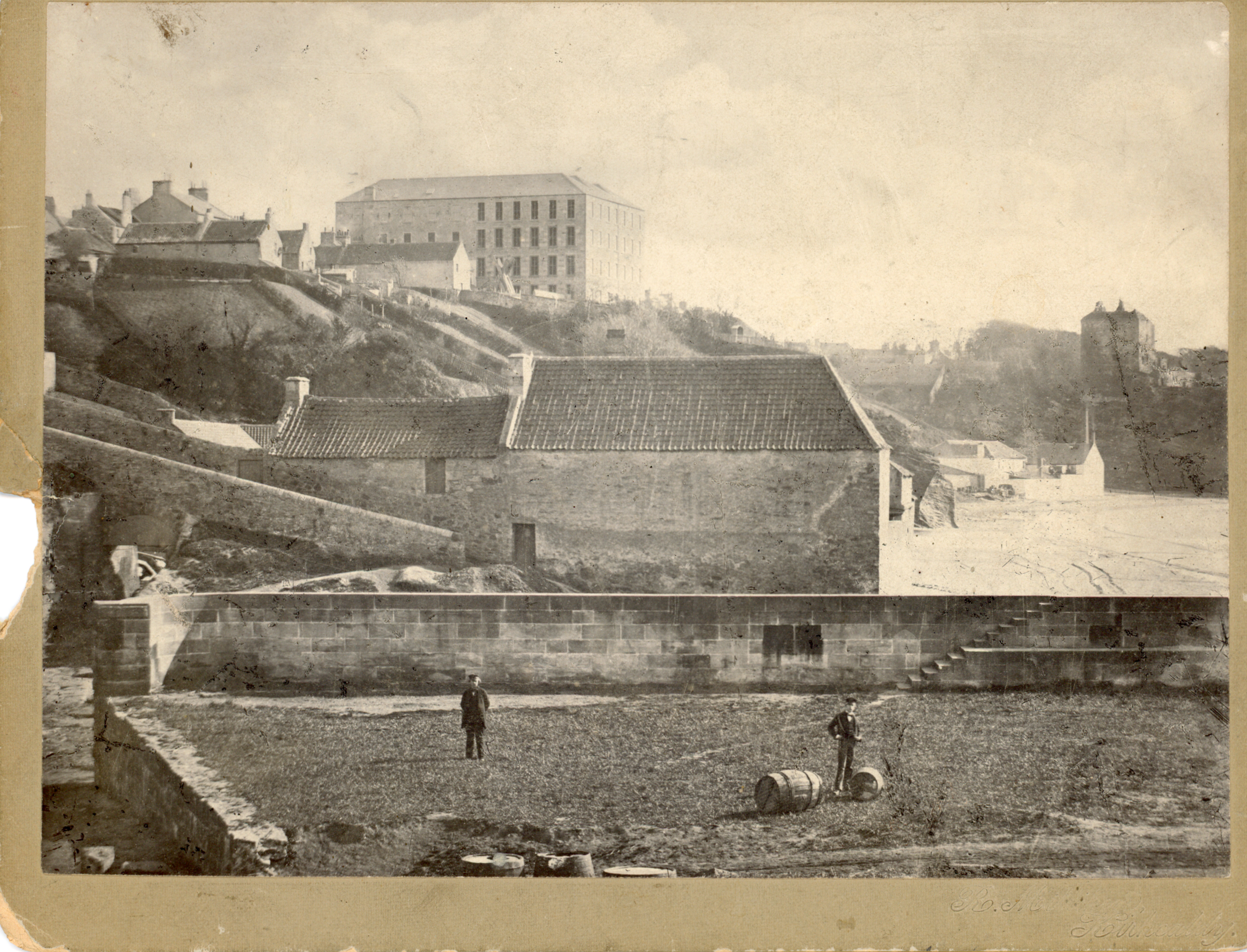

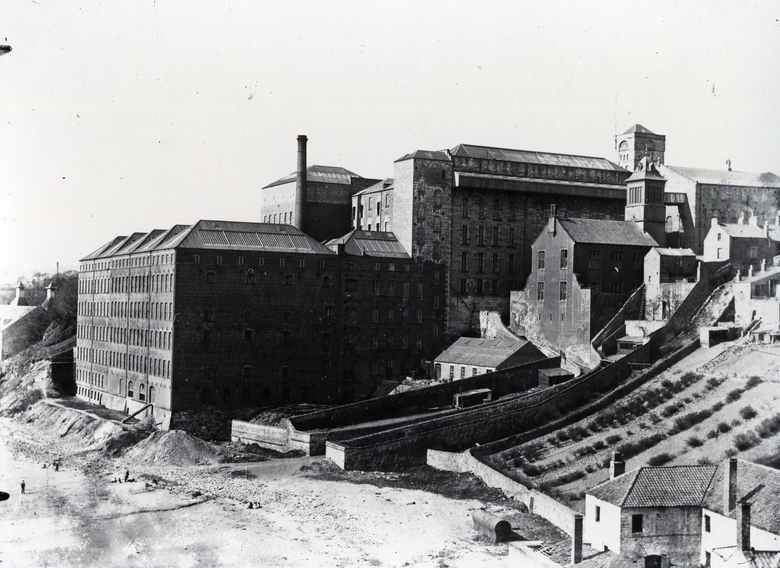

The first floorcloth factory in Scotland was built by Michael Nairn in the Pathhead area of Kirkcaldy. Known colloquially as ‘Nairn’s Folly’, this massive factory was the first stepping-stone in Nairn’s evolution from a small-scale canvas manufacturer to one of the most prolific producers of floorcoverings in the world.

A view of the beach below Ravenscraig castle. Nairn’s Folly is the large building on the top of the cliffs.

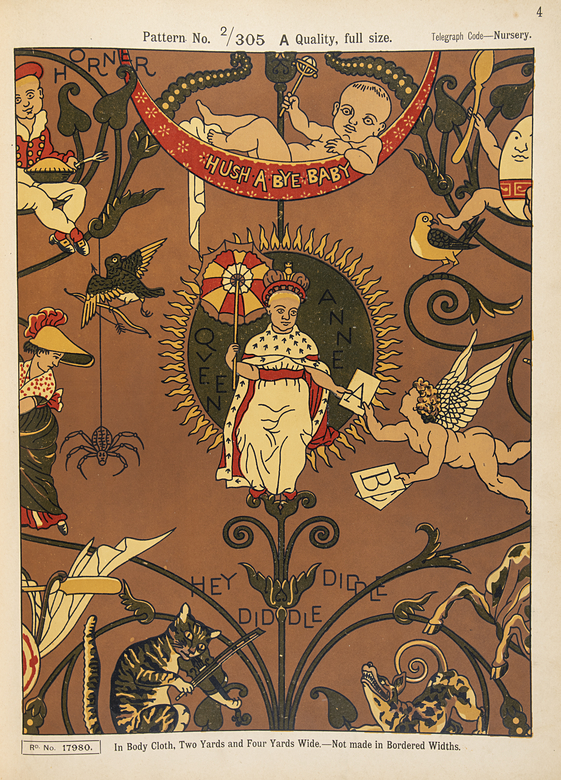

Floorcloth itself had existed for centuries; the earliest known reference to it in the UK is in the inventory of a house called Denham Hall in 1736! It was similar to linoleum, and was made of many of the same ingredients and using similar processes. A paste made from resins, cork dust, wood flour and coloured pigments was painted onto a canvas backing. These layers were built up on either side of the canvas, so that each side was smooth and waterproof. A patterned design would then be printed on the ‘top’ side. These could then be used, like rugs or carpets, to cover dirt, wood or stone floors.

For the first 30 years of their foray into floorcoverings, Nairn’s focused exclusively on floorcloth. From 1877, they produced both floorcloth and linoleum, until the former dwindled away in the first few decades of the 20th century.

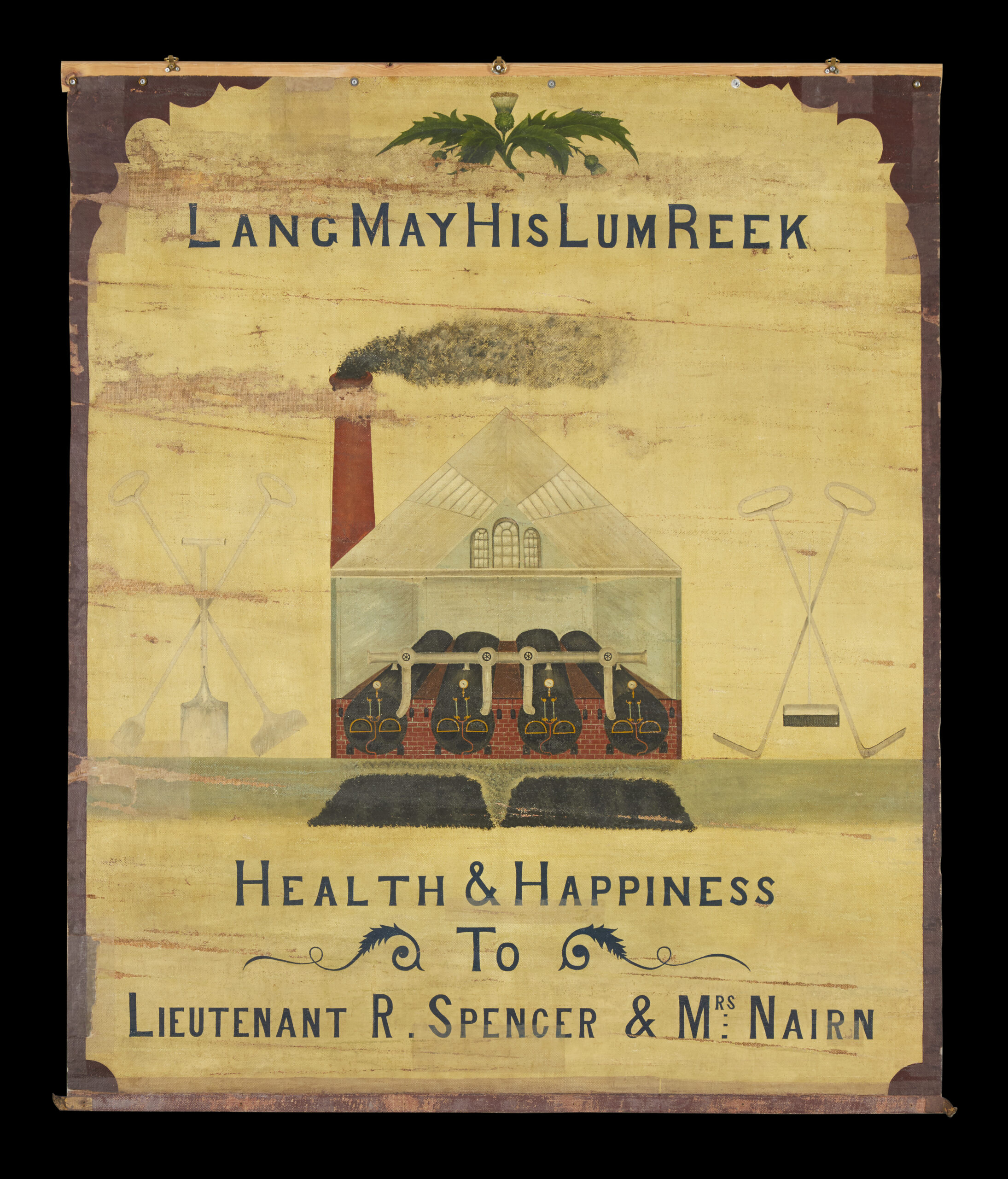

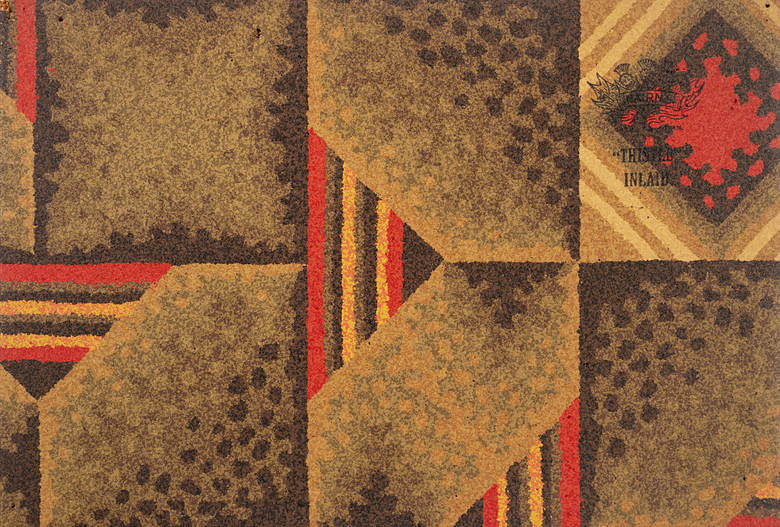

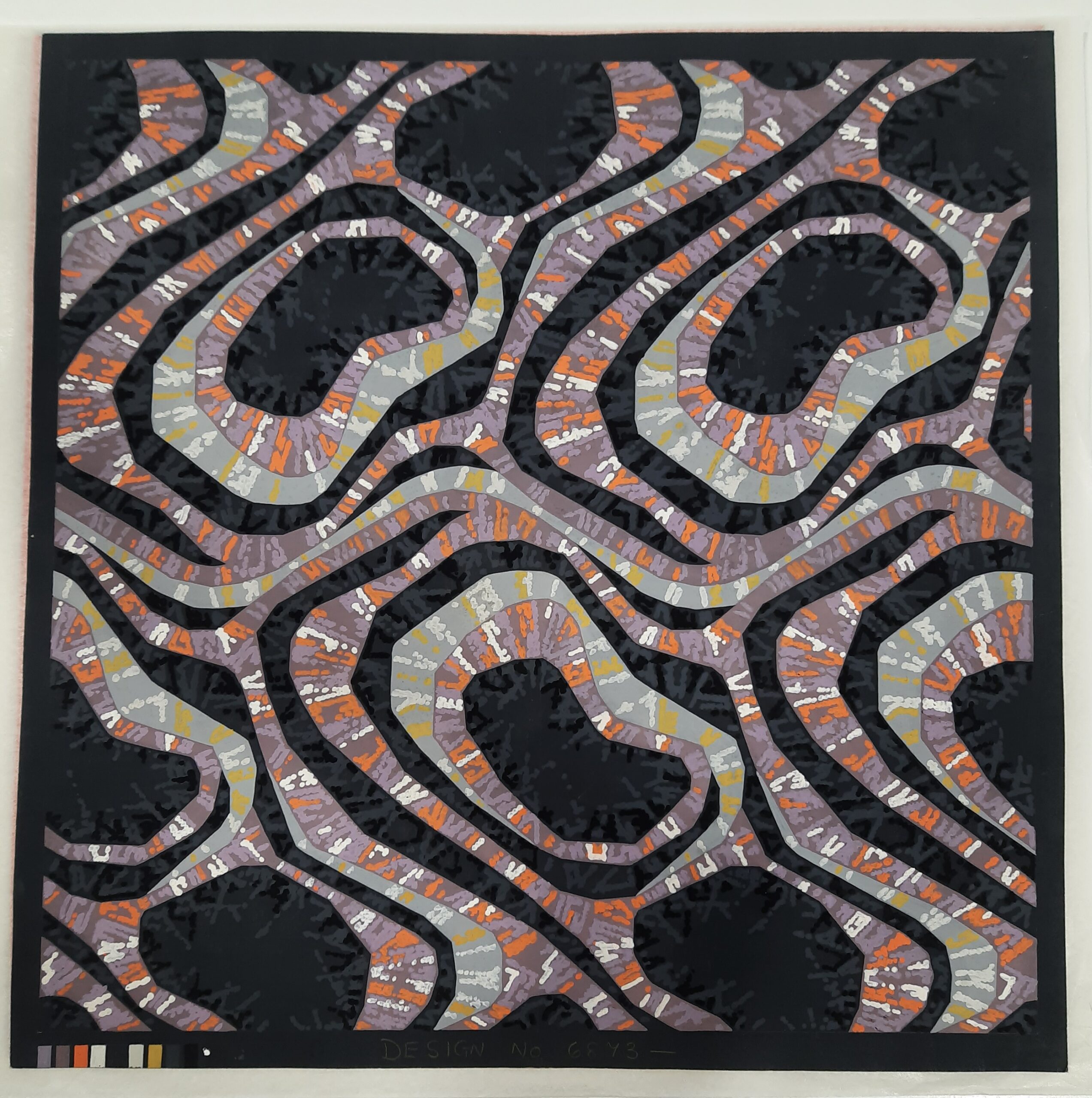

A floorcloth banner from our collection. The first image shows the design painted on the ‘bottom’ of floorcloth. The second shows the printed ‘top’, which would become the back of the banner when it was carried.

For Nairn’s however, floorcloth wasn’t just for floors. From the late 19th century up until the First World War, it was used to create a series of hand-painted banners, which were carried in processions by the workers. The patterned ‘top’ side of the floorcloth became the back of the banner, and the plain ‘bottom’ side was painted with a design and slogan. Usually, these praised the Nairn family or the products made by the company.

We know from photographs and secondary sources that dozens of different banners were made. Today, only five are known to survive – all in our collection. We are not currently aware of any other banners like this in the world, so it is possible that these are the only five in existence.

A floorcloth banner from our collection, created in 1907.

This banner was created by the engineers and fireman from Nairn’s Folly floorcloth works to commemorate the wedding of Robert Spencer Nairn on 6 July 1907. To mark the occasion, the Nairn family organised a workers’ excursion to their estate in Rankeilour (near Cupar, Fife). This would have been the first time this banner was carried.

A photograph showing the Nairn’s workers marching with floorcloth banners during their 1903 excursion.

At the beginning of the day, Nairn’s workers gathered at each of their places of work across the town. The first group then set off from the Canvas works, marching towards Nether Street where their colleagues from the Floorcloth Works would join them as they passed Mid Street. An article in the Fife Free Press (dated 13 July 1907) records that all the banners in our collection were made and carried by the Floorcloth Works group, who also wore floorcloth caps and sashes.

After a short interval, the Linoleum workers would join in behind them, led by a foreman carrying a sword. The Trades Band played at the front of the procession, and the Pathhead Band played at the back.

The itinerary produced for the 1907 Summer Excursion.

All workers then boarded special trains at Sinclairtown station, where they were taken north to Rankeilour. In total, over 2,400 people attended, as each worker was permitted to bring a family member or friend along with them.

On arrival there, they enjoyed an early lunch (served at 11:30), followed by dinner at 16:30. In between, they played the sort of games you’d expect at a summer fete (including the sack race and the egg and spoon race) and a Highland games (including a caber toss).

The Nairn’s workers at Rankeilour during their 1905 Summer Excursion.

We know from other excursion itineraries in our collection that these excursions happened on at least two other occasions during this decade – first in 1901, and next in 1905. However, it is possible that this trip to Rankeilour may have been the last in which our floorcloth banners were used.

This banner was conserved in 2020, and is currently on display at Kirkcaldy Galleries.

We know that this banner was carried along with ‘Lang May His Lum Reek’ in 1907. From conservation in 2020, we know that this banner had the date on it repainted each time it was carried. As the date visible was the last time it was updated, it is possible that this was its final outing. If this is the case, then it is likely that our ‘Lang May His Lum Reek’ banner was also only carried on this single trip.

Interested in seeing our floorcloth banners in person?

‘First in the Field’ is part of our permanent displays in Kirkcaldy Galleries and can be seen in the Moments in Time gallery, opposite the café.

‘Lang May His Lum Reek’ will be going on display as part of the Flooring the World exhibition, which will open at Kirkcaldy Galleries on 25 November 2023.

It is also possible to see two of the three remaining banners at our collections store in Bankhead, Glenrothes. You can make an appointment to see them by e-mailing museums.enquiries@onfife.com

_______________________________________________

Flooring the World is a two-year project exploring the history of the Fife linoleum industry. It is funded by the Esmée Fairbairn Collections Fund, which is run by the Museums Association.

![]()

The First and Second World Wars had a profound impact on daily life around the world, and Fife was no exception. In particular, the outbreak of war – and the peace in between – provoked changes to the types of jobs which were done in Fife, and the kind of people who did them.

In this blog post, we’ll explore how the World Wars changed the role that women played in the Fife linoleum industry by examining photographs from our museum collections.

If you would like to learn more, we’ve just installed a temporary display on this subject in our Moments in Time gallery at Kirkcaldy Galleries. This will be on display until the end of August 2023, and you can see it any time during the Galleries’ regular opening hours.

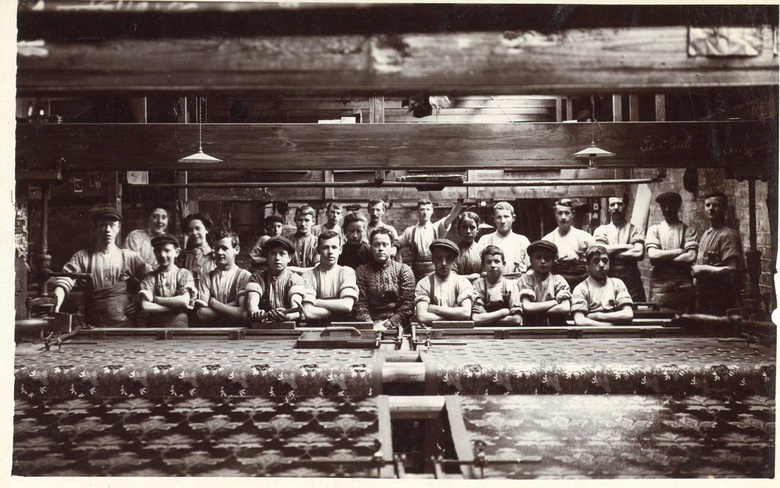

Image: A group of floorcovering workers in the printing loft of the Tayside Floorcloth Company, c.1890 – 1910. (CUPMS1990.0070)

The First World War is often understood as the time when women first entered the workforce en masse, dramatically changing the demographic of – particularly – industrial workplaces. However, that is not to say that women were entirely absent from the workplace before this time.

Women – particularly poor women, women of colour, and women from otherwise marginalised communities, such as recent immigrants – have always had to work to support themselves and their families. Though many felt that certain types of work (or, perhaps, even the idea of work at all) were inappropriate for members of the ‘fairer sex’, eschewing employment was a luxury that few women could afford.

This photograph shows workers in the printing loft at the Tayside Floorcloth Factory, Newburgh, probably at some point between 1890 – 1910. In it, we can see five women and nineteen men and boys. This suggests that, although they were outnumbered, women were still present, and in some cases even represented a significant proportion of the workforce.

We don’t know the specific professions of the people in this photograph. Nonetheless, it does seem likely that they were photographed in the space that they regularly worked, and therefore that this image shows a team largely made up of printers. This indicates that – in at least some workplaces – women were not segregated from men, that they worked in the same spaces as them, and potentially did the same or similar roles.

As we will see in later images, this was not necessarily consistent across the Fife linoleum industry. However, this photograph indicates that conditions like these were not unheard of, even if they were not the norm.

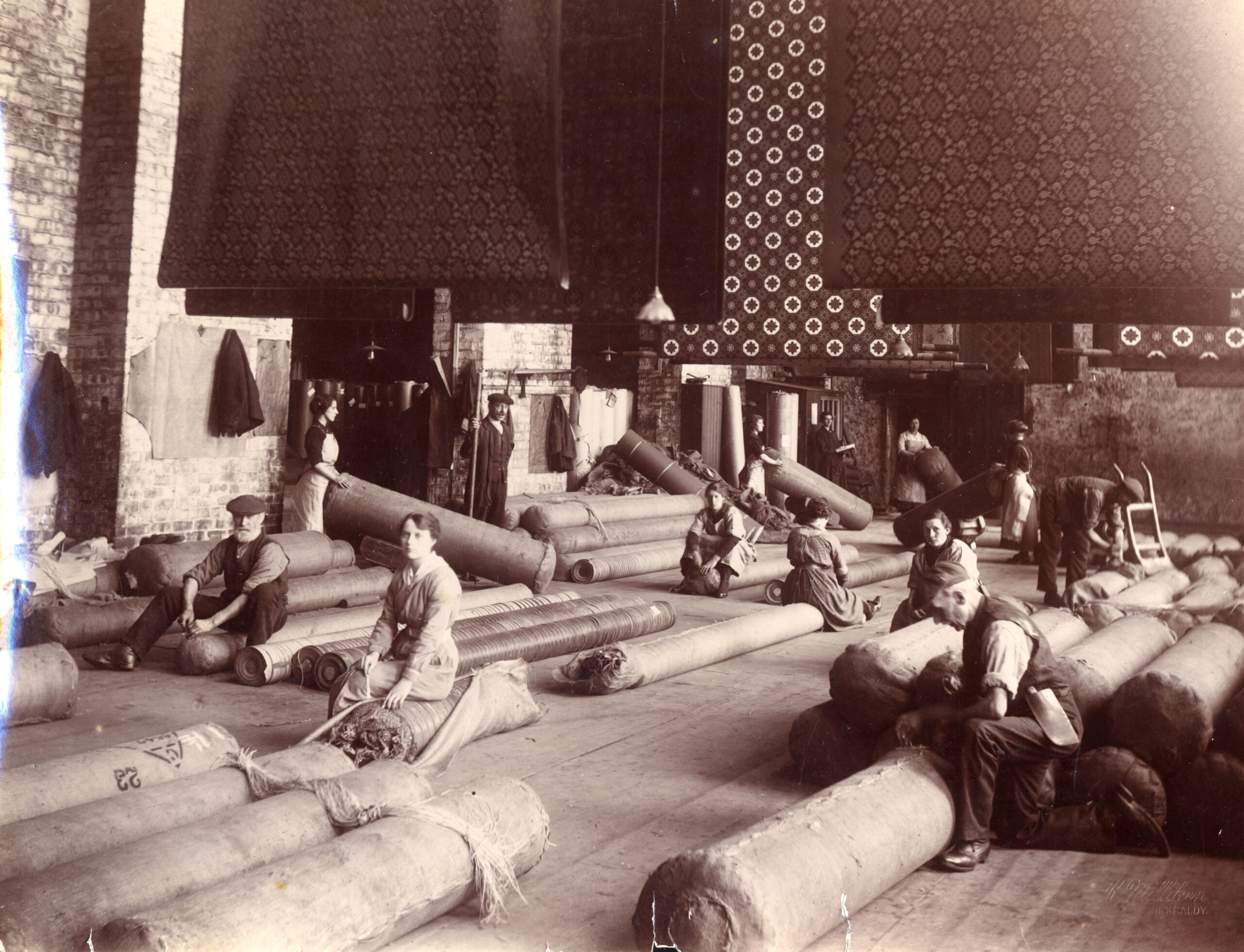

Image: A team of workers in Kirkcaldy in one of Barry, Ostlere and Shepherd’s factories, Kirkcaldy. 1914 – 1918. (KIRMG:1991.0231)

In January 1916, the British Government passed the Military Service Act, which required all men aged between 18 and 41 to join the Armed Forces. This meant that a new workforce had to be found to work in the jobs they left behind.

Skilled, conscription-aged men were replaced with unskilled and semi-skilled women workers, who learnt their new trades on the job. The men who remained were older and often held senior or managerial roles due to their greater lengths of experience.

Across the country, many teams working in factories would have therefore looked something like this. This team made up almost entirely of women, apart from the three men who appear to be above conscription age.

Another notable thing about this image is that some of the women are wearing trousers. This is very unusual; in the vast majority of the photographs in our linoleum collections, working women are shown wearing skirts and dresses. This ‘masculine’ dress-code was again temporarily permitted during the war. Women could dress ‘like men’ while they were doing ‘men’s work’ – but both of these things were understood as strictly temporary measures.

Sadly, we do not know what this team was working on at the time they were photographed. It is possible that they were manufacturing munitions and other goods required by the war effort.

Image: A linoleum despatch room, Kirkcaldy. Of the photographs in our collections which show workers in linoleum factories during WWI, the majority were – like this one – taken in factories operated by Barry, Ostlere and Shepherd in August 1918. (KIRMG:1986.0097)

Many of the women employed in industry during WWI found themselves manufacturing products for the war effort. However, many factories also continued – at least in part – to make whatever they produced during peace time.

This photograph shows workers in the despatch room at one of Barry’s factories, preparing finished linoleum for delivery. From this, we can deduce that linoleum production – for the domestic market – continued through the war, and that women were involved in its manufacture.

Image: Women stoking the boilers in one of Barry, Ostlere and Shepherd’s factories, Kirkcaldy. August 1918. (KIRMG:1986.0095)

Aside from weapons and linoleum, there were also some jobs that simply had to be done regardless of what was being done in the rest of the factory. The women in this photograph are shown stoking the boilers – a task which had to be completed day in, day out, come rain or shine.

Image: Canteen staff at Michael Nairn and Company Limited, Kirkcaldy. 1935. (KIRMG:1983.0633)

Following the end of hostilities, the British government, Trade Unions and other influential groups were eager for working life to get back to normal as soon as possible. This meant women giving up their jobs in favour of the men who had vacated them and, preferably, returning to domestic work (either unpaid in their own homes, or paid in the houses of others).

Nonetheless, through both choice and necessity, some women did remain in the workforce. Usually, women were encouraged into roles which were extensions of the sort of work they would do at home. This included cleaning and, like the canteen workers pictured in this image, cooking.

Image: Clerical staff at one of Barry, Ostlere and Shepherd’s factories, Kirkcaldy. 1920s. This photograph is from a series in our collection which show teams of Barry’s workers. (KIRMG:1980.2620)

There were a few exceptions to this rule, including clerical work. Since the 1880s, administrative tasks had increasingly become associated with women workers. Over the next few decades, this would continue to the point where it became almost quintessential. Even today, we still associate these kind of roles – secretaries, assistants and receptionists – with women.

There are a few reasons for this. Firstly, the typewriter was a new piece of technology, which required previously non-existent skills to operate. As such, women could take up this role without having to face the stigma of having ‘taken a man’s job’.

Secondly, compared to other types of work, administrative tasks were relatively clean and quiet. This dispelled fears from moralists that work was unladylike, and would naturally coarsen women until they were uncivilised (or worse, unattractive to men). A typist could carry out her work and still embody the traits which – in the late 19th and early 20th centuries – were seen as synonymous with womanhood.

Finally: size mattered. As women, on average, had smaller hands than men, it was assumed that they would naturally be more dextrous. Women were naturally suited to typing, because their dainty fingers would be better suited to operating the machine.

Image: Twins Catherine and Janet Fortheringham making inlaid linoleum. Though this photograph dates from c.1959 – 1964 the task was associated with women long before this. (TEMP:2012.4426)

Strangely, the assumption that smaller hands were faster, more dextrous hands may also have led to another job in the linoleum industry becoming the preserve of women.

Throughout the history of the linoleum industry, the production of inlaid linoleum has been a task primarily associated with women. This was a highly skilled process, by which pieces of different coloured linoleum were fitted together to make a pattern. Unlike printed designs, inlaid designs would remain intact regardless of how much the floorcovering was worn down – the colour of each piece went all the way to the back, so the design was much longer lasting.

Image: Workers making fuel tanks for Halifax bombers at one of Michael Nairn and Co. Ltd.’s factories, Kirkcaldy. 1939 – 1945. (TEMP:2012.4431)

When WWII broke out, women once again returned to Kirkcaldy’s factories.

This time, there was a greater focus on producing goods for the war effort. Women working at Nairn’s manufactured fuel tanks for Halifax bombers, as well as munitions.

In 1946, Nairn’s published a book celebrating their workers’ contributions to victory. In this, they stated that perhaps their biggest contribution was the production of anti-gas fabric, which was made into capes and gas-masks. The fabric had to be impregnated with linseed oil, a key ingredient used in the manufacture of linoleum (and which gives the floorcovering its name: ‘lin’ meaning linseed and ‘oleum’ meaning oil). In the book, Nairn’s wrote that this was a decisive factor in the Allies victory. As the Nazis could not manufacture gas-proof textiles in sufficient quantities, they never used gas in air raids for fear of retaliation. As such, they were unable to use a decisive weapon which may have given them the upper hand.

If you would like to learn more about Women, War and Linoleum, we’ve just installed a temporary display on this subject in our Moments in Time gallery at Kirkcaldy Galleries. This will be on display until the end of August 2023, and you can see it any time during the Galleries’ regular opening hours.

_______________________________________________

Flooring the World is a two-year project exploring the history of the Fife linoleum industry. It is funded by the Esmée Fairbairn Collections Fund, which is run by the Museums Association.

![]()

From the 1950s, linoleum faced one of the greatest challenges in its history – one which influenced the way the product was marketed for decades.

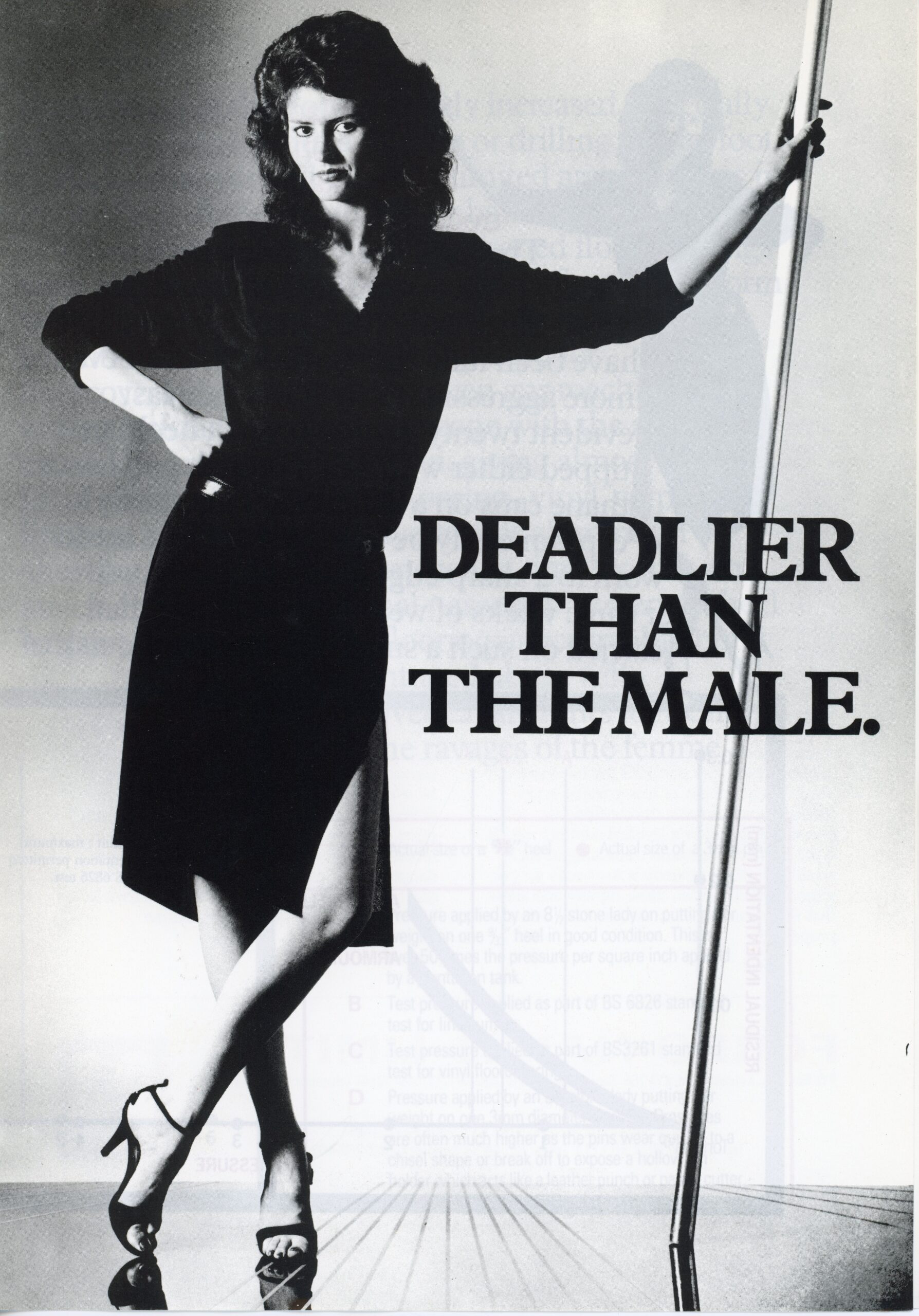

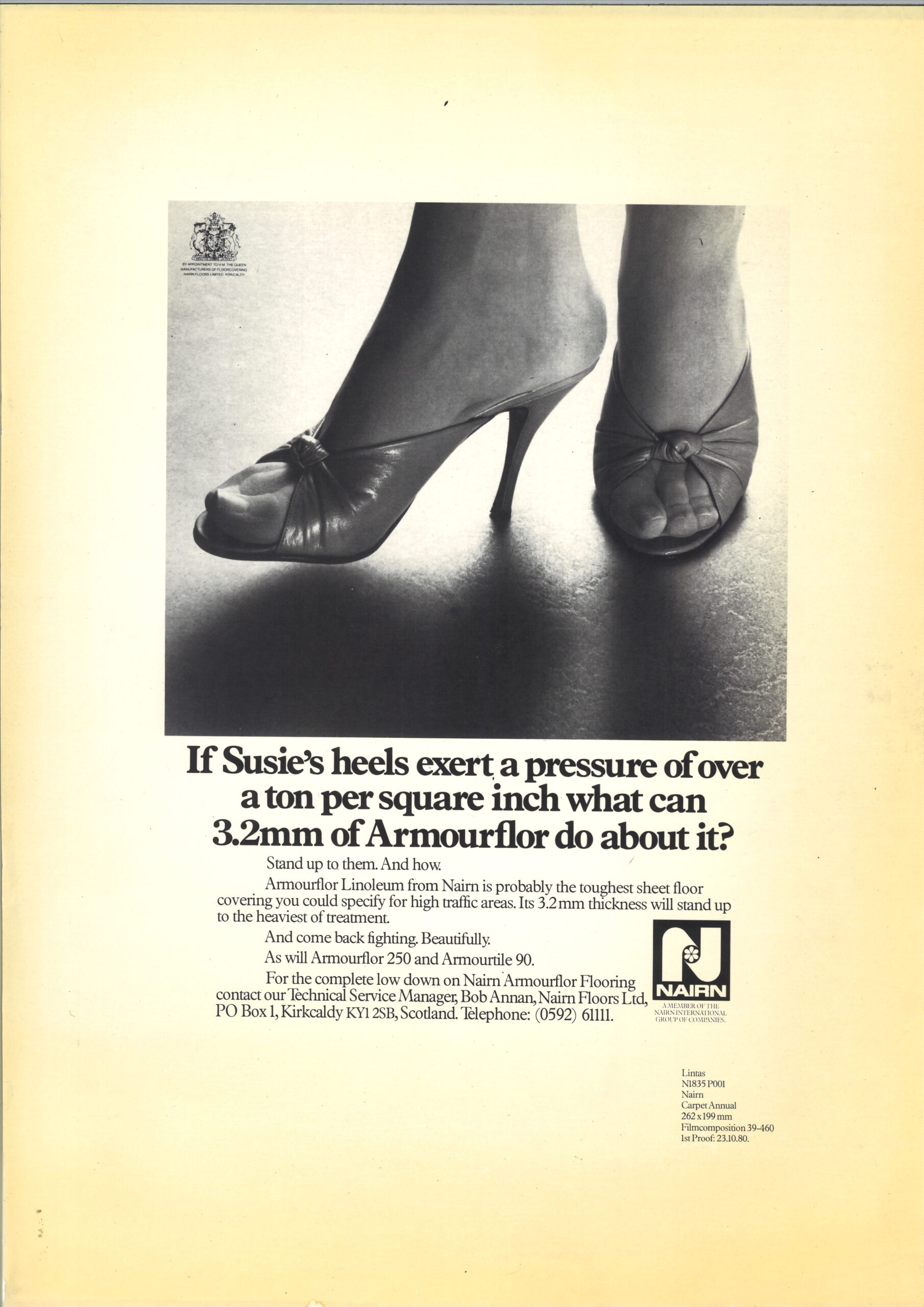

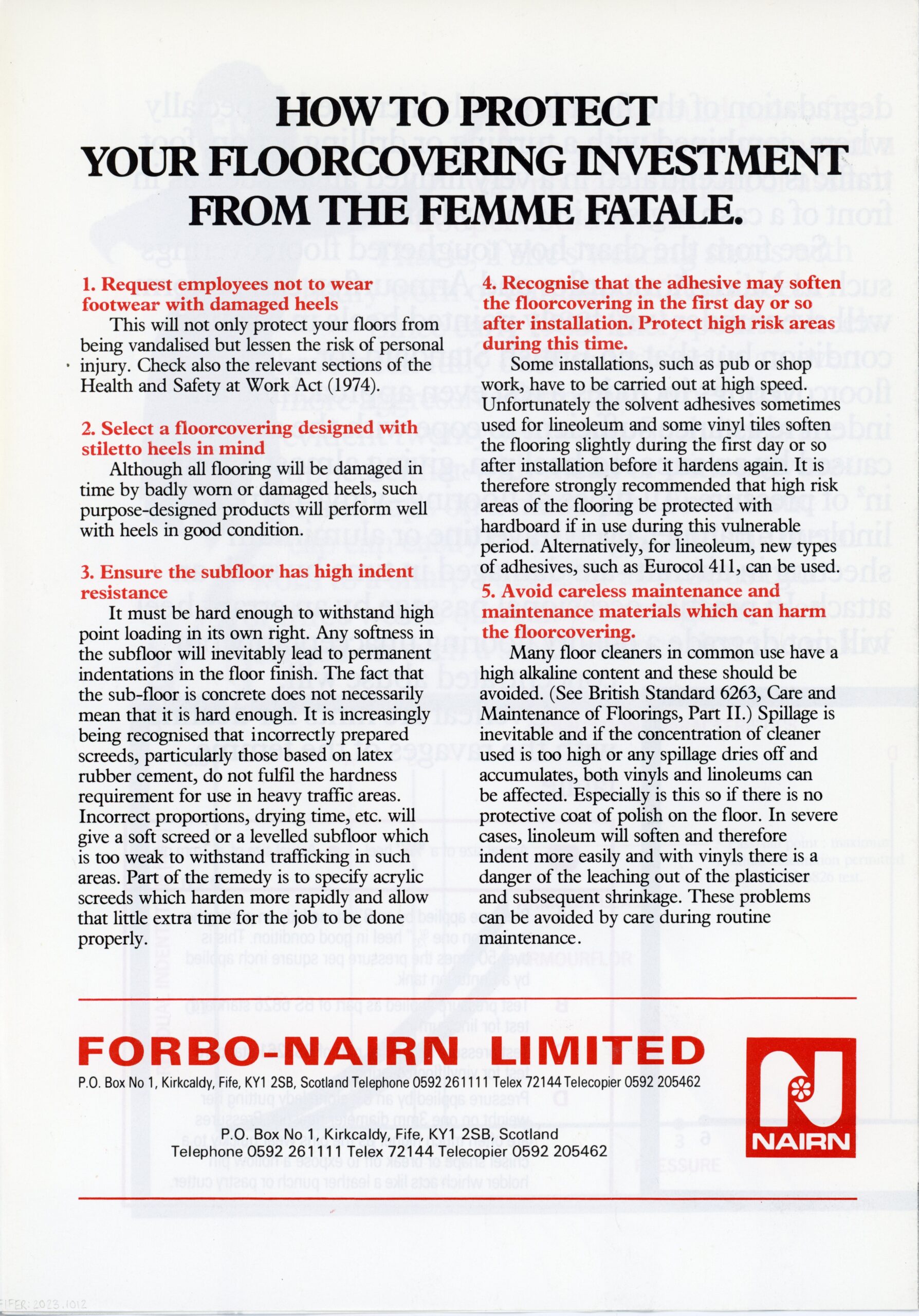

Let’s start with a image. A black and white photograph of a woman, standing in a non-descript space. Below her is a slogan: Deadlier than the male. But the words don’t refer to the woman, or to her fluffy hair, or her dark dress, or her direct stare. Instead, they’re directed at what’s on her feet: a pair of strappy, open-toe shoes with a short, thin heel.

Image: Promotional booklet produced by Forbo-Nairn, c.1985.

The stiletto heel was first developed in the 1930s, though their original inventor is disputed. The design was made possible by the use of a thin metal core within the heel which gave it its strength and structure (as well as its name – a stiletto was a thin dagger which came into use in 15th century Italy). In the 1950s, this design was popularised French designers Andre Perugia and Roger Viver. By the 1960s, the stiletto heel had spread across Europe and North America, and was synonymous with style, sex appeal and glamour.

However, the rise of the stiletto was not just a concern for the fashion conscious; in the mid-twentieth, stiletto heels were on the minds (and in the nightmares) of every linoleum manufacturer in the world.

Heeled shoes had been walking over linoleum for as long as it had existed. The difference here was that the thin heel of the stiletto concentrated the wearer’s weight in a far smaller area, exerting a far greater pressure on the floor beneath. It is estimated that a stiletto heel worn by a person weighing 65kg exerts twelve times the pressure of a four-tonne elephant standing on one foot.

These high pressures meant that wearers left small indentations in linoleum floors as they walked. The increased popularity of stilettos, alongside the ubiquity of linoleum in both public and private buildings, meant that the damage was apparent to everyone. As lino’s reputation came under fire, both manufacturers and consumers became concerned about the longevity of the previously reliable floorcovering.

As such, manufacturers began to fight back with advertising. Theoretically, these stressed improvements to linoleum in the face of the new challenge of stilettos. In practice, while demonising the shoes they also laid the blame squarely at the heeled feet of the women who wore them.

Stilettos had very quickly become symbols of femininity to the point, even acting as a shorthand for signalling gender; for example, Minnie Mouse is essentially identical to Mickey, except for her high heels. Damage done by heels then, was damage done by women. Linoleum under attack from not just a shoe, but from an entire gender.

The rise in the popularity of stiletto heels came at a time when women were entering the workforce en masse. They were working in larger numbers, and in more diverse roles than ever before. At the same time as many were becoming concerned about the impact of shoes on linoleum, others were worried about the impact of this social change on the established order of things.

Let’s return to our advert. On the reverse, it includes a series of tips for protecting floorcoverings from the femme fatale. While most of these concern the floorcoverings themselves, the first tip simply suggests that stilettos be banned from the workplace. Dress-codes like this had been prevalent in offices since the 1950s, and were always enforced with the express desire of protecting floorcoverings. However, as stilettos had become very much symbolic of women as a whole, perhaps we can also see this trend in the context of anxieties over women’s liberation. Was the desire to have no stilettos in the workplace also partly a desire to have less women in the workplace too?

It would be wrong to suggest that linoleum advertising was in any way leading the charge when it came to sexism. However, these adverts can be seen as artefacts of a general perception of gender which – though it did not raise eyebrows at the time – now seems both dated and problematic.

________________________________________________

Flooring the World is a two-year project exploring the history of the Fife linoleum industry. It is funded by the Esmée Fairbairn Collections Fund, which is run by the Museums Association.

![]()

As we reach the end of the first year of the Flooring the World project, curator Lily shares some of the things the project has achieved over the last twelve months.

February

Image: Block made up of layers of ink. FIFER:2022.0184

One of the first things I did when I joined OnFife was visit the archive at the Forbo Factory on Den Road. The firm, initially as Michael Nairn’s and then to Forbo through a series of name-changes and mergers, has been producing floorcoverings in Kirkcaldy since 1847. They have offered their entire archive to us as part of the project, and I’ve spent a lot of time this year working through their amazing objects, documents and photographs deciding what to bring into our collections.

I accessioned this strange object after my first visit. It’s a block made up of layers of ink used to print designs on linoleum. It was cut from a spot under the floorboards in one of the – now demolished – Nairn’s printing lofts – over the decades, waste ink had dripped between the boards and built-up layer by layer. This block is a literal slice of history.

Image: RMS Queen Elizabeth, made out of linoleum. FIFER:2022.0147

Another new addition to the collections was this brilliant picture made of out linoleum. It shows the ship the Queen Elizabeth at sea, and was probably made in the late 1930s. We don’t know who made it, but suspect it was probably created in Fife. Read our post on this curious object to find out more.

I also got the change to visit Newburgh, another key site in the story of the Fife linoleum industry. While the factory buildings which made up the Tayside Floorcloth Company complex are now gone, the imprint of the industrial is still visible in the town. One place you can find a trace of it is in the Laing Museum – the patterned floor of the museum is original printed floorcloth which was laid in the 1890s.

Image: Floorcloth at Laing Museum, Newburgh

March

Image: Page from a pattern book. FIFER:2022.0150

In March, using funds provided by the Friends of Kirkcaldy Galleries, we had some of the objects in our collection photographed. Some of these – like the pattern book above – were new arrivals from the Forbo archive. Others, like the medal below, had been in our collection for some time. Medals like these were awarded to manufacturers at World’s Fairs and Expositions during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Perhaps the most famous of these was the Great Exhibition in London, 1851 – sometimes known as the ‘Crystal Palace’. Nairn’s were unlucky at this fair, but took notes on the products displayed by other floorcovering manufacturers to improve their processes. The research paid off, and for years afterwards they regularly returned home from these trips with a brace of accolades.

Image: Linoleum medal, brass, Allgemeine Deutsche Patent und Mustedrschutz Ausstellung in Frankfurt A. M. 1881, M Nairn & Co. TEMP:2011.1529

April

Image: Floorcloth banner. KIRMG:1983.0078

April saw the long-awaited return of one of our gorgeous floorcloth banners to Kirkcaldy Galleries. This banner went out for conservation before the start of lockdown in 2020 but, in order to keep everyone safe, it wasn’t possibly to reinstall it until 2022. The banner is one of five known to exist – all of which are in our collections. It was created by workers at Nairn’s at some point between 1900 – 1905, with a design painted on the plain underside of a printed floorcovering. Its conservation was generously funded by the Friends of Kirkcaldy Galleries.

Image: Back of the floorcloth banner. KIRMG:1983.0078

I also changed over the display in our Moments In Time case in Kirkcaldy galleries. At the beginning of the project I set myself the (perhaps overly ambitious goal) of changing the objects in this case once every three months. I began with a selection of objects from the Forbo archive, including the paint block I mentioned above.

May

In May I had the opportunity to share the project with other people working in museums across Scotland. I gave a presentation at the Scottish Museum Federation’s annual conference, introducing them to the wonderful world of linoleum and sharing the work that had been done so far. I also got the chance to show National Trust for Scotland curators Antonia Laurence-Allen and Emma Inglis (curators for Edinburgh and East, and Glasgow, respectively) around our stores. We spoke about the fascinating history of linoleum in Scottish houses, and talked about places where it can still be seen in situ today.

June

Image: Linoleum lent to V&A Dundee. FIFER:2022.0167

In June we had a visit from staff from V and A Dundee, who selected some samples of linoleum to go in their exhibition Plastics: Remaking Our World. Linoleum is not a synthetic plastic, but a biodegradable substance made of natural materials derived from plants. The objects were included to help illustrate some of the first materials which were designed to solve the same problems which were later resolved by plastic – perhaps by revisiting these older materials we can find an answer to the problems plastic in its turn has caused. These samples will be coming back to us soon, but you can still see some gorgeous inlaid lino in their Scottish Design gallery.

Image: Linoleum sample on long-term loan to V&A Dundee. FIFER:2017.0016

I also got a chance to write up some research I’d been doing, inspired by the many beautiful linoleum designs in our collections which were clearly intended for children’s rooms. Most of the patterns in our collections – be they in books or samples – are fairly neutral, and would be suited to any space. The exception is a small group of very intricate, complicated designs featuring characters from nursery rhymes. I wanted to find out more, and if you do to, then you can click here to read all about it.

Image: In a pattern book produced by the Kirkcaldy Linoleum Company, 1876 – c.1900. FIFER:2022.0150

July

Shh! In July I was invited along to talk about linoleum for a forthcoming TV programme. I can’t tell you too much about it yet, but watch this space!

By July, it was already time to change the Moments In Time case. This time I opted to go for a selection of objects and photographs which told the story of Kirkcaldy linoleum in the 1960s – a dark decade which saw the loss of much of the city’s industry. I wanted to try something a little bit different, so supported this display with a playlist of songs which were popular at the time, to help conjure up memories of times gone by. You can listen along here.

Image: 1960s linoleum.

August

In August I was lucky enough to record the first oral history of the project. This involves going out to meet people who worked – or who had relatives who worked – in the linoleum industry, and speaking to them about their working life. These recordings become a part of our collection, and can be accessed by anyone interested in the industry to help them to learn more about the lived experience of those would made the linoleum industry possible.

For my first oral history recording, I spoke with someone who designed patterns from linoleum at Newburgh, first for the Tayside Floorcloth Company, and then for Barry Staines. They also kindly donated some of their hand-painted designs, which were created between 1959 and 1969.

I am hoping to record even more oral histories in 2023. I’d like to speak with anyone and everyone who worked (or who had family members who worked) with linoleum, or anyone who has a story to tell me about the industry in Fife. I’d be particularly keen to hear from those who have memories of the industry in Falkland, as this is somewhat underrepresented in our collections.

If you’d like to learn more, please get in touch using the contact details at the bottom of this post.

September

Image: Newburgh Ancestry and Family History Society visit.

In September, we welcome the Newburgh Ancestry and Family History Society to our collections stores at Bankhead. The group were there to see a selection of objects relating to Newburgh, including some of the wonderful photographs in our collection showing the town’s linoleum industry.

October

Patented!

I was invited to speak about the history of lino on Patented, a podcast produced by History Hit. She chatted with host Dallas Campbell about how linoleum was invented, and how – via a ground-breaking legal trial – it made its way to Kirkcaldy.

We also welcomed the first of our linoleum store tours! This meant welcoming two groups to take a guided tour around our collections store at Bankhead, before giving them the chance to get up close and personal with a selection of objects, documents and photographs from our linoleum collection. This included a chance to see the newly conserved Paolozzi elephant (more about them in December!).

Finally, I changed over the Moments in Time case in Kirkcaldy Galleries to feature a display about the in-house fire brigades employed by linoleum factories. You can learn more about them in this blog post.

Image: Collections store tour.

November

November saw another round of tours, with yet more visitors getting to see our collections in the flesh. We’re looking forward to running more of these in 2023, so if you’re interested in coming along please get in touch using the contact details at the bottom of this article.

I also collected another load of boxes from the Forbo Archive – these were the last to enter our collection this year. In total, we accessioned over a nine hundred objects, documents and photographs from the Forbo Archive in 2022 – and there is lots more to come in 2023!

One of my favourite things from the archive is this photograph of two men holding a floorcloth banner, probably dating to c.1900-1909. The banner is now lost, so this photograph is our only record of it.

Images: Photograph of workers with a floorcloth banner. TEMP:2012.4439

December

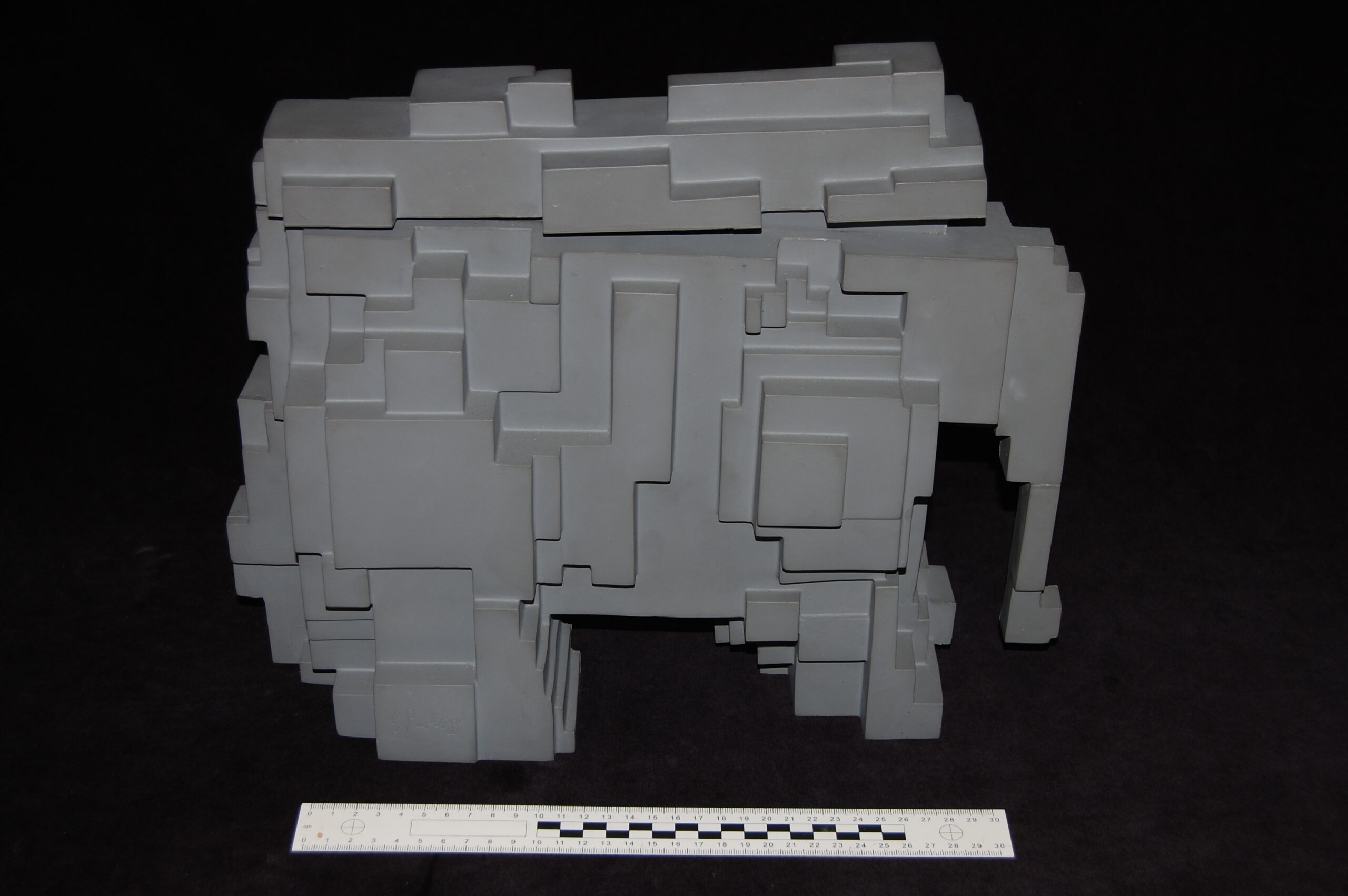

Image: Paolozzi elephant. FIFER:2022.0235

Remember those elephants I mentioned earlier? Well, following conservation they both went on display in Kirkcaldy Galleries, where you can see them until the beginning of March 2023. If you’d like to learn more about these peculiar pachyderms, check out our previous blog post here.

We also welcomed a piece of William Morris patterned linoleum into our collections. The sample was a gift from the William Morris Society Hammersmith, and is a piece of the only linoleum ever created from the Morris Company. It is believed to have been manufactured in Kirkcaldy in the 1870s. We haven’t had a chance to have this photographed yet, but are looking to have it on display in Kirkcaldy Galleries later in 2023.

January

In January I installed a new display in the Moments in Time gallery, this time featuring buildings associated with the linoleum industry which were demolished during the 20th century. I’ll be changing this display again in April – so watch this space!

What’s next?

2023 is going to be a very exciting year for the Flooring The World project. We’ll be working with communities in Newburgh and Falkland, as well as volunteers in Kirkcaldy, on some exciting projects which we’ll share later in the year. Plus we’ll be working on our exhibition, which will open at Kirkcaldy Galleries in November.

We’ll also be continuing to improve our collections, and to collect oral histories from those with first or second hand experience of the linoleum industry. If you have memories you’d like to share, please get in touch – no story is too small!

If you’re interested in being involved with the Flooring the World project, you can reach me by e-mailing lino@onfife.com, or by calling 07548777008. You can also keep up to date with the project by following the project page on Facebook, or by following Kirkcaldy Galleries and OnFife Museums on Instagram, Facebook or Twitter.

________________________________________________

Flooring the World is a two-year project exploring the history of the Fife linoleum industry. It is funded by the Esmée Fairbairn Collections Fun., which is run by the Museums Association.

![]()

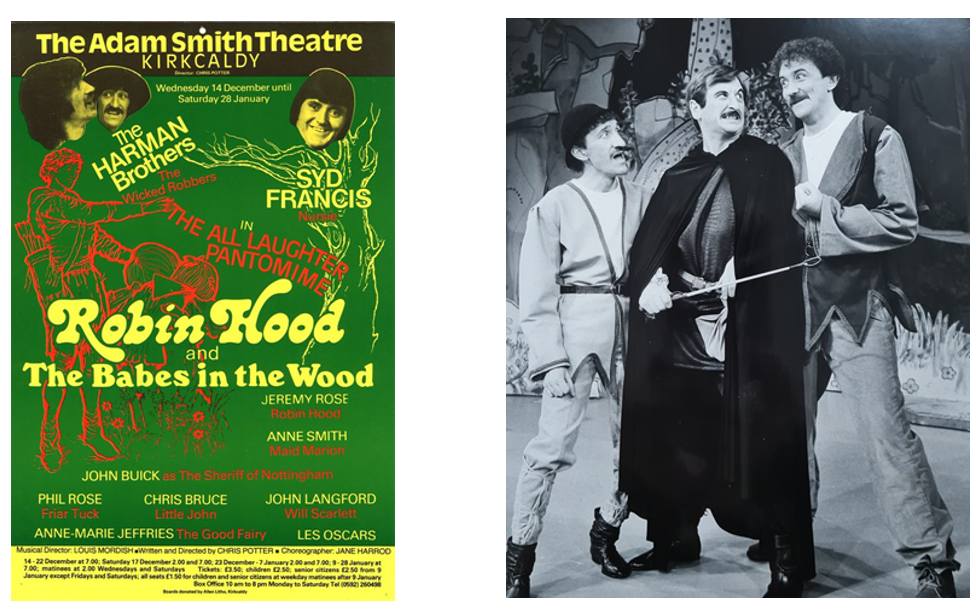

When the Adam Smith Theatre closed its doors for refurbishment in 2020, OnFife Museums were offered a collection of programmes, photographs and posters dating from the 1970s to present day. Amongst them material from the yearly pantomime. After a two-year break, our pantomime returns this Christmas at the Rothes Halls while the Adam Smith Theatre redevelopment continues. It wouldn’t be a pantomime without singing, dancing, slapstick comedy, audience participation (He’s behind you!) and of course the Dame with their extravagant costumes. Let’s take a dance down memory lane and look at the pantomimes of Christmas past at the Adam Smith Theatre.

In 1981, The Harman Brothers (known to many as The Chuckle Brothers) made their first of three appearances at The Adam Smith Theatre in Puss in Boots.

Poster for Puss In Boots featuring the Harman Brothers in 1981, FIFER:2022.0141

In 1982 they returned to play Policemen Yoo and Mee in Aladdin, alongside Danny O’Dea as Window Twanky and Dean Park as Wishee Washee.

LEFT: Poster for Aladdin in 1982, FIFER:2022.0141 RIGHT: The Harman Brothes (as Yoo and Mee) with Danny O’Dea (Widow Twanky), FIFER:2022.0095

In 1983, The Harman Brothers’ third appearance – this time as the Wicked Robbers in Robin Hood and The Babes in the Wood.

LEFT: Poster for Robin Hood and The Babes in the wood in 1983, FIFER:2022.0141 RIGHT: The Harman brothers as Will and Wont with John Buick as the Sheriff, FIFER:2022.0096

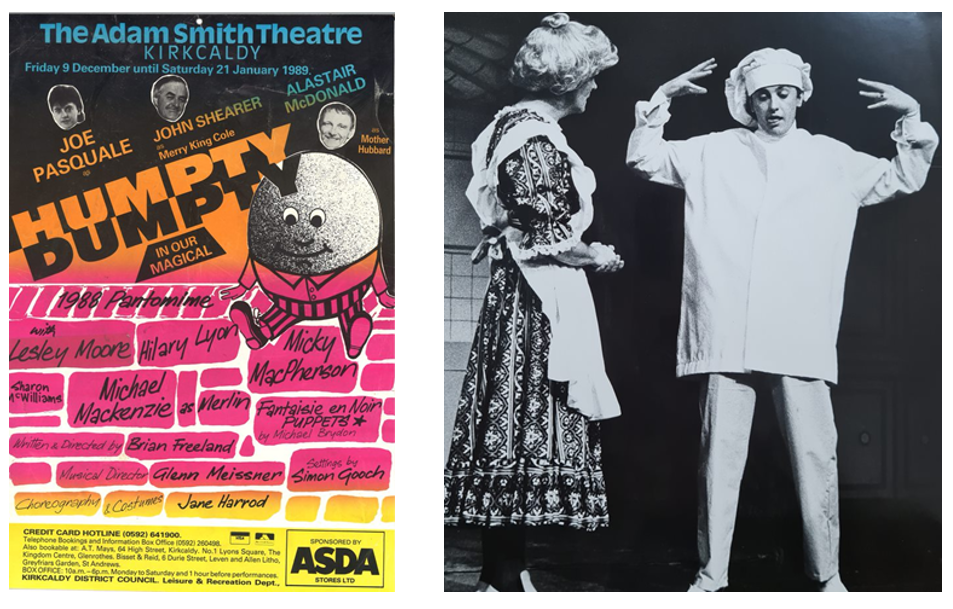

In 1988, another famous face took to the stage in an adaptation of the nursery rhyme, Humpty Dumpty, written and directed by Adam Smith Theatre’s General Manager Brian Freeland.

LEFT: Poster for Humpty Dumpty in 1988, FIFER:2022.0141 RIGHT: Joe Pasquale as Humpty Dumpty with Alasdair McDonald as Mother Hubbard, FIFER:2022.0100

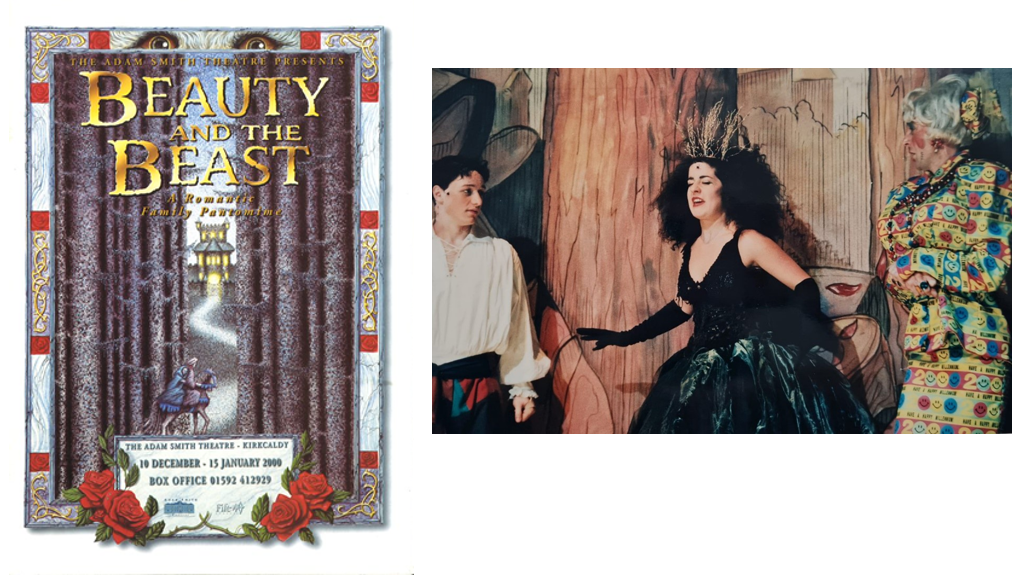

1999 saw James McAvoy as Bobby Buckfast the daft wee son of Betty Buckfast (Alan McHugh). Together Betty and Bobby worked together to protect Beauty (Fiona Steele) and see that she came to no harm from Sadista the Sorceress (Anita Vettesse).

LEFT: Cover of programme for Beauty and the Beast, FIFER:2022.0069 RIGHT: Bobby Buckfast (James McAvoy, left), Sadista the Sorceress (Anita Vettesse, middle) and Betty Buckfast (Alan McHugh, right), FIFER:2022.0104

What an amazing costume Dame Betty Buckfast is wearing above! Extravagant, bright and very on subject of the time with the 2000 detail. Dames’ costumes often reflect the local area and current matters. In this case marking the coming millennium.

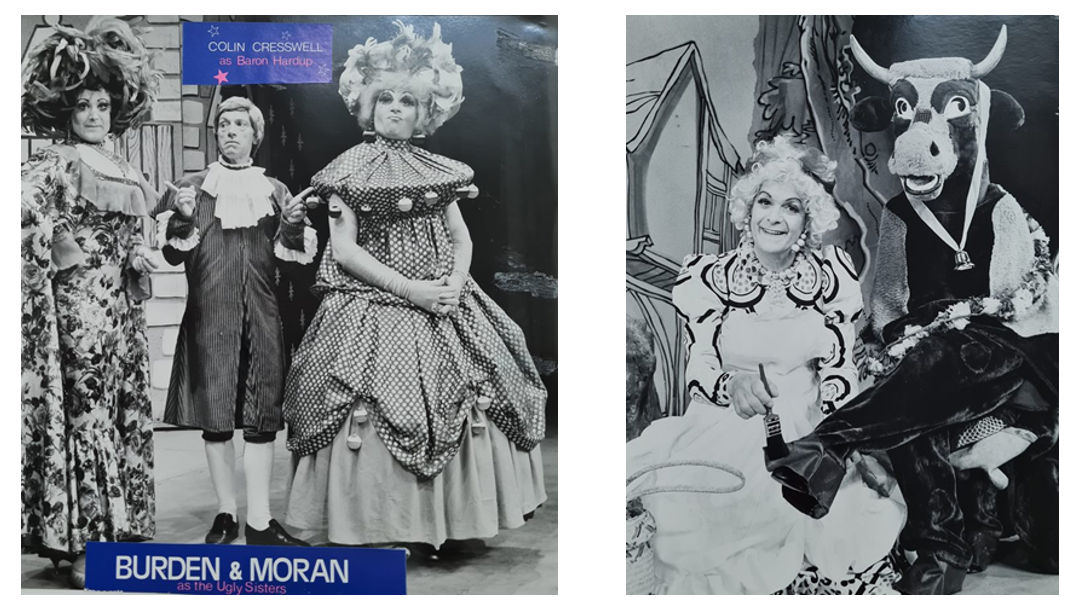

Here are some other pantomime characters for you to enjoy:

Mother Goose in 1975, FIFER:2022.0091

LEFT: Burden and Moran (the Ugly Sisters) with Colin Cresswell (Baron Hardup) in Cinderella in 1982, FIFER:2022.0094 RIGHT: Mary Lee as Jessie the Cook with cow in Dick Whittington in 1984, FIFER:2022.0097

LEFT: Nurse Polly Esther (James Murray) with Queen Semolina (Eileen McCallum) and King Tapioca (Martyn James) In Sleeping Beauty in 1995, FIFER:2022.0102 RIGHT: Alan McHugh as Jack’s Ma in Jack in the Beanstalk in 2000, FIFER:2022.0105

Programme for Mother Goose in 2015 featuring Billy Mack, FIFER:2022.0071

Programme for Jack and the Beanstalk in 2019, FIFER:2022.0071

The last pantomime to be held at The Adam Smith Theatre before it closed for its redevelopment was Jack and the Beanstalk.

What are your favourite memories of the Adam Smith Theatre pantos? Share them in the comments below! Happy panto season!

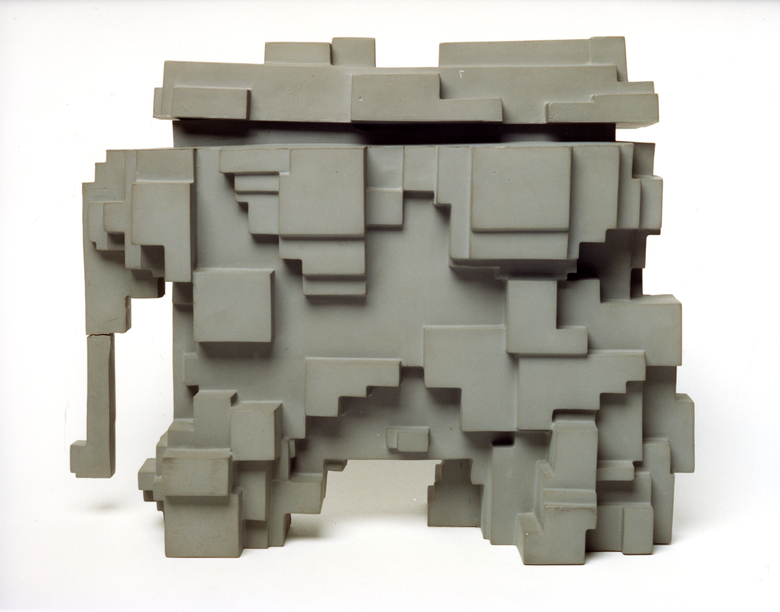

As our Paolozzi elephants return to our museum stores, we take a closer look at these plastic pachyderms.

Picture the scene. Its 1970, and you’re a Scottish floorcovering manufacturer looking for a way to display brochures at tradeshows and in showrooms. It needs to be tidy, eye-catching, and chic enough to capture attention of potential customers. Obviously, the answer is to commission one of Scotland’s most influential artists to create you a series of 3000 elephant-shaped boxes.

Sounds like a leap, but that’s exactly what happened. At the time of the commission, Nairn Floors were in a strange position. They had survived the tumultuous decade of the 1960s, remaining a player in an industry that had changed dramatically. Between 1963 and 1970, a vast number of linoleum factories in Kirkcaldy had been demolished, and Nairn’s was now the only firm making floorcoverings in the town.

They had also diversified into vinyl floors, and would try their hand at carpet. As they began to diversify, they looked to consolidate their position by advertising their products to architects. These were coveted clients as, if they specified a certain brand or style of floorcovering for a large project, Nairn’s could guarantee bigger sales than they could secure with customers looking to floor individual homes. There was also the possibility that architects might come back time and time again, whereas domestic sales were – by the nature of linoleum’s long life-span – less likely to garner regular repeat purchases.

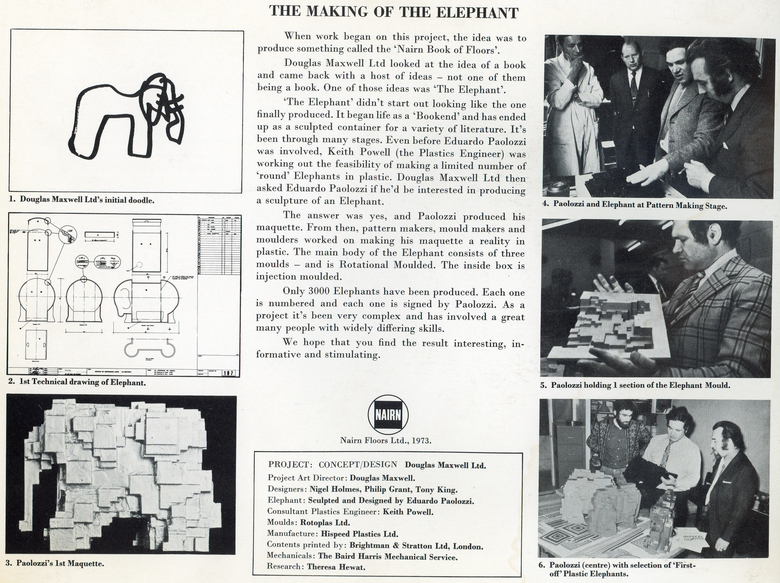

Initially, the company approached a design company called Douglas Maxwell Limited, with the idea to produce a volume called the ‘Nairn Book of Floors’. The company took the brief, and came back with several ideas – one of which was not a book at all, but an elephant. The idea was that the elephant would act as an attractive ‘bookcover’ but that the pages kept inside it could be updated as products changed.

Seems logical enough – but why an elephant? We’re a bit unclear on how that happened. Was it due to the elephantine pressure linoleum could withstand through a stiletto heel? Or perhaps the longevity of linoleums lifespan put some in mind of mammoth memories? The answer is most likely a mix of the two, supported by a universal truth: everyone likes elephants.

Each elephant was accompanied by a booklet explaining the design process, with Paolozzi’s signature unmissable on the front cover.

At the time, Eduardo Paolozzi was already a big name in the art world. Born in Leith in 1924, Paolozzi is considered by some to have provided a name to the era-defining Pop art movement, by including the word ‘Pop!’ in his 1947 collage If I Was A Rich Man’s Plaything. By 1972, he could boast one-man shows at MoMA, the Tate and the Scottish National Gallery (which now holds his full archive). Obviously, the next logical step was to make an elephant for Nairn’s. It seems a strange move, but of the project Paolozzi said:

“The object was exciting to me as a sculptor. In one sense, what could be more organic than an Elephant? (Or the idea of an Elephant?). To interpret this into completely non-organic shapes, practically all geometric elements, with an emphasis on the horizontal and vertical planes, was a fascinating problem. […] I was aware beforehand of the various technical processes the sculpture would have to undergo, but found that many of the craftsmen involved were using a technology of a very fine kind, and this opened an entirely new world to me.”

The elephants – while strange and unusual to us – were inspiring to Paolozzi. They introduced him to new techniques which he would later use in his own work – most notably the Cleish Castle Ceiling.

To create the elephants, he began by producing a maquette – or model – which ‘pattern makers, mould makers and moulders’ developed into a final design. Each elephant was accompanied by a booklet which detailed the process, in which it is modestly described as “very complex”.

3000 elephants were made and, though they occasionally pop up for sale in auction houses, today only a few are accounted for. There is one in the Metropolitan Museum in New York, one in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London – and two are held by us in our Collections Store at Bankhead, Glenrothes.

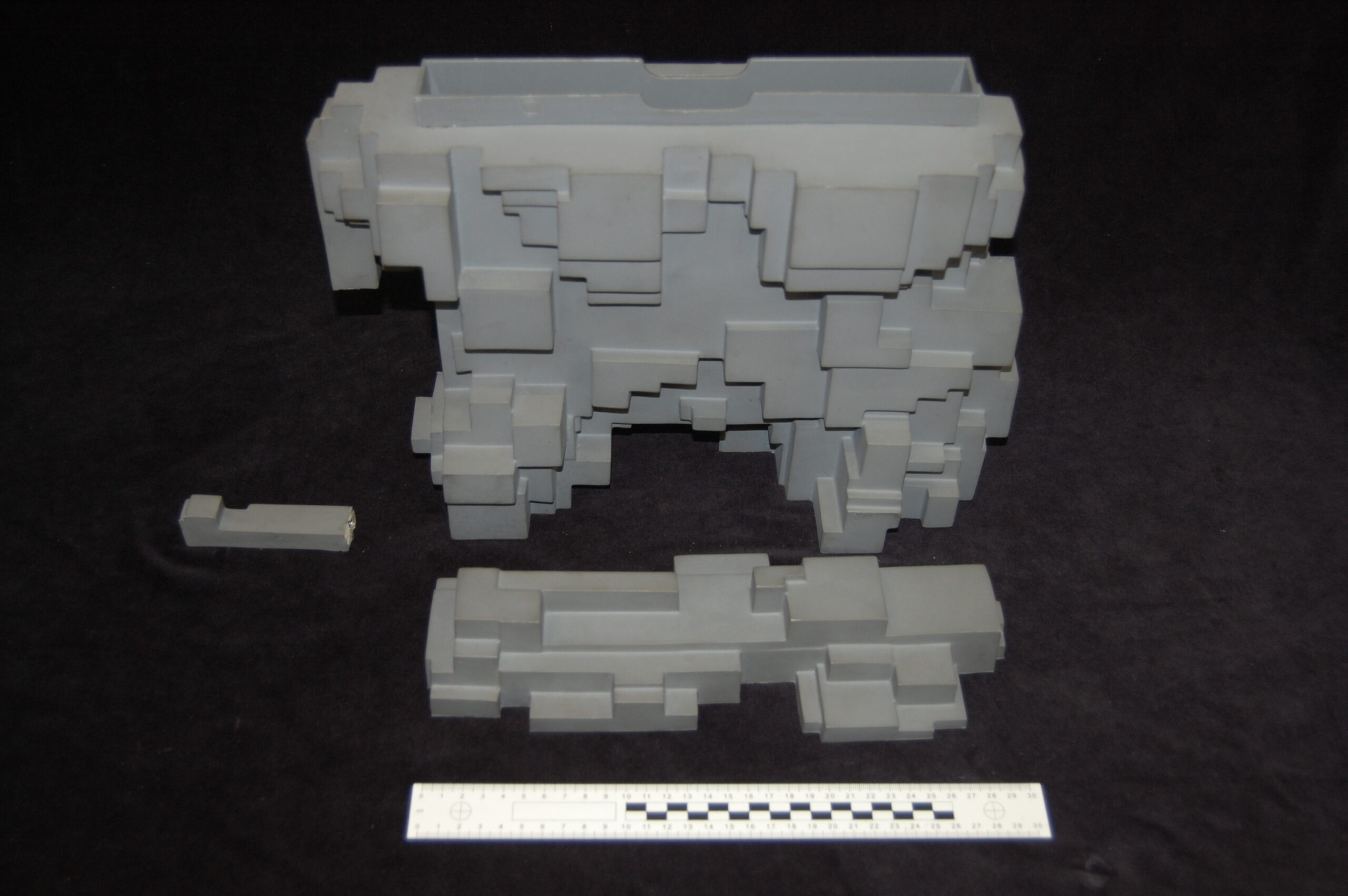

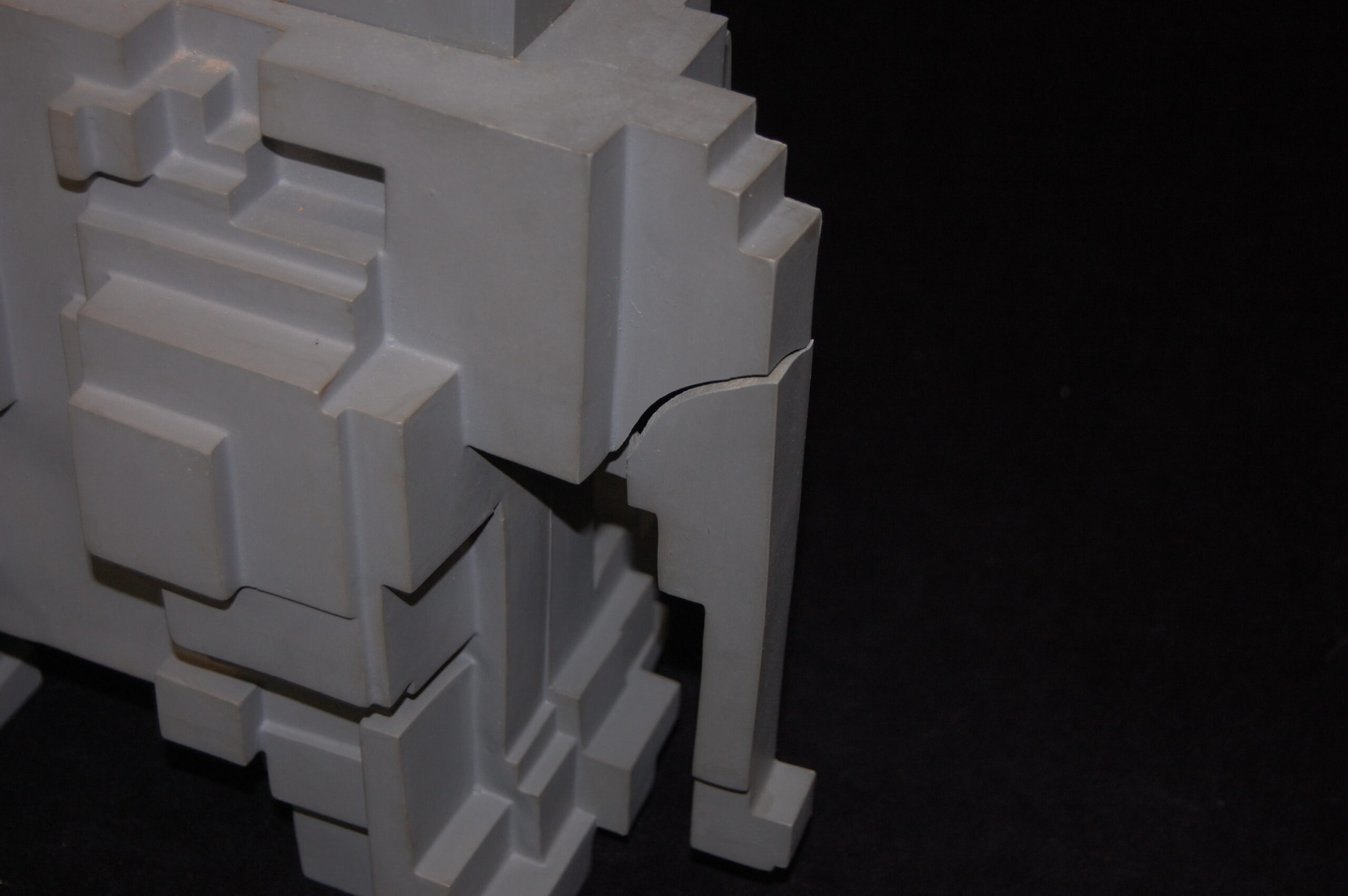

The first – marked number 768/3000 – had been with us for some time, and over the course of its life had lost its trunk. The second joined our collections this year. This one is not numbered, which may hint at it being a production proof outside of the run of 3000, perhaps produced especially for Nairn’s to keep – waiting in the archive until Nairn’s became Forbo, and Forbo chose to donate their archive to OnFife. This one had fared slightly better, but still had a few cracks across its surface.

Number 768, before conservation. KIRMG:1986.0300

While we’re all aware of the devastating environmental impact of plastic, many people are not aware of how difficult it is to preserve and care for. As it ages – which can be exacerbated by light or heat – plastic begins to deteriorate. This deterioration manifests in different ways, depending on the type of plastic; some become brittle and crack, some flake apart, some appear to melt, and most of these processes produce gasses which can damage other objects around them. On top of this, it is very difficult to tell the hundreds of different types of plastics apart. This makes care and preservation even more difficult; if we do not know what we are dealing with, we cannot tailor our behaviour to best suit its needs.

The unnumbered elephant from the Forbo Archive, with a few cracks across its surface. FIFER:2022.0235

This proved to be an issue when it came to the elephants. It was impossible to identify which kind of plastic they were made out of and, as such, the conservator could not predict how they might behave in future. Ultimately, this led to us deciding to only conserve one of them – 768. While this elephant’s trunk could be repaired using a dowel, the cracks on our unnumbered elephant would require adhesive, which could cause further damage in future if the plastic were to expand or contract. To protect both as much as possible, we opted for different treatments. Together, the pair make a perfect ‘before’ and ‘after’.

Number 768 after conservation, re-trunked and ready to go!

Our original elephant wasn’t included in the Queer-Like Smell exhibition in 1992, so the pair have yet to make their debut appearance at one of our venues. Until now! You can find the elephants at Kirkcaldy Galleries from 16 December 2022 – 8 March 2023.

Flooring the World is a two-year project exploring the history of the Fife linoleum industry. It is funded by the Esmée Fairbairn Collections Fund, which is run by the Museums Association.

A restored prehistoric pot, currently on display in Kirkcaldy Galleries, was discovered when a human skeleton was dramatically exposed by builders behind Kirkcaldy High Street in 1980 in what is now a car park. It is the focus of new research uncovering untold stories of the find and celebrating Kirkcaldy’s Bronze Age heritage.

A dig was carried out in Kirkcaldy in 1980. Image: TEMP:2012.4175

Found in large broken pieces, the fired clay pot was first rebuilt in 1980 by archaeologists at The University of Glasgow who undertook the rescue excavation. It has now been fully restored by a conservator thanks to the generosity of the Friends of Kirkcaldy Galleries.

Pot sherds as they were first found. Image: TEMP:2012.4183

The vessel after it was rebuilt by archaeologists at The University of Glasgow in 1980. Image: KIRMG:1981.1819

Vessel, after being conserved at the Scottish Conservation Studio in 2022.

Initially when first discovered the burials was widely reported in the press as being associated with a type of Earlier Bronze Age pottery known as a Beaker. In fact, it belongs to a different contemporary ceramic tradition and the pot is a Food Vessel. Of European origin, Beakers were established here a few centuries before the appearance of Food Vessels, and while the two overlap in time, they are recognized as distinct ceramics associated with apparently different practices. The relationship between these different ceramics and their users continues to be the focus of much archaeological debate. Radiocarbon dating and new analytical techniques such as isotopic analysis are adding intriguing evidence about the lives, health and mobility of the prehistoric people buried with such pots.

As a specialist in this type of pottery, I undertook a detailed examination of the Kirkcaldy High Street vessel ahead of its recent conservation and reconstruction. Found across Scotland, Food Vessels date from 2560-1450 BCE. These pots often accompany both inhumation and cremation burials in purpose-built cists – distinctive rectangular stone constructions – with the deceased. Historically assumed to have served as containers for food for the afterlife or the funeral feast (hence their name), current studies suggest that some of these pots were previously used in domestic settings for the cooking or storage of dairy products.

In terms of appearance, individual pots come in a variety of shapes and sizes. Hand-made each is similar but different, often sharing decorative elements found on other vessels. Most stand 10-25 centimeters tall with flat bases and impressed or incised linear decoration. Around 80% of the original pot survives, it is 16.5 cm high with a rim diameter of 16 cm with traces of coil construction.

The shape of the Kirkcaldy High Street Food Vessel is commonly found throughout Scotland. It has two prominent ridges and an intermediate groove on the shoulder, and a slightly rounded tapering lower body. It is decorated with comb impressions and a common herringbone design around the neck. Similar decorated vessels have been found on other sites in Fife, as well as in most other areas of Scotland. Such common features reveal creative connections among well-connected bronze age communities. The potters were drawing on a shared knowledge of decorative motifs and techniques.

Visual similarities between Beakers and Food Vessels can be seen. These ‘drinking vessels’, while displaying a different range of forms, often feature very similar styles of decoration to those found on Food Vessels. Similarly, Beakers mainly survive in cists but are found more commonly with individual adult burials where the body is lying in a crouched position on one side.

A total of three cist graves were uncovered during the Kirkcaldy High Street 1980 excavations. But only one had a Food Vessel. Human remains were also present in one of the other previously disturbed burial cists. Specialist analysis will soon reveal further insights into the people buried in this small cemetery on an earlier sandy raised beach back in the Bronze Age.

The new research is part of an ongoing project at The University of Glasgow to address unpublished archaeological excavation archives. The original excavator died before completing the original analysis. There is much to uncover from digging through older discoveries in museum stores. Working in partnership with OnFife Collections Curator Jane Freel the project includes events to share the results and celebrate the discovery and the prehistoric past with the local community.

Keen to find out more?

- Visit our window display at Kerry Photography, 243 High Street, the site of the original burial (on display until the end of September).

Window display at 243 High Street, Kirkcaldy

_________

This blog was written by Dr Marta Innes – Archaeologist, Freelance British Prehistoric Pottery Specialist and Illustrator

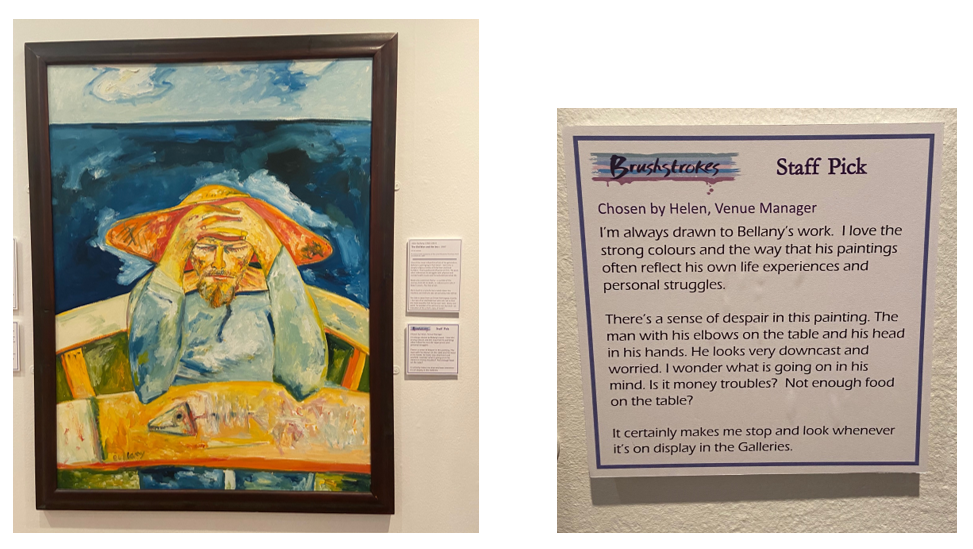

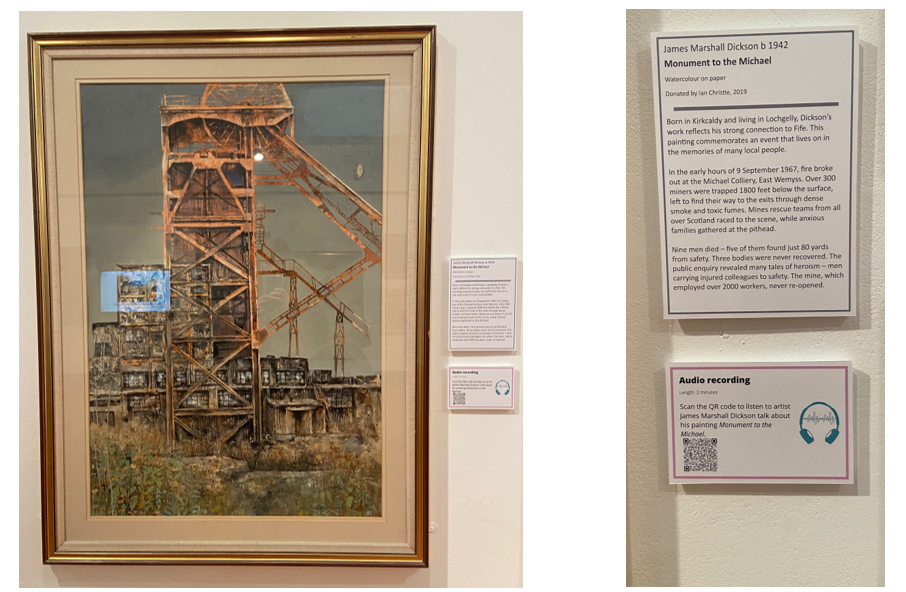

In June, Kirkcaldy Galleries opened its doors to two colourful and exciting new exhibitions – ‘Jack Vettriano: the Early Years’ and ‘Brushstrokes’. Featuring specially selected gems and highlights from our own permanent fine art collection, ‘Brushstrokes’ was designed to complement the Vettriano exhibition, to show off our fantastic collection, and to trial new display layouts and engagement methods.

Right here on your doorstep in Fife we have around 2,000 oil paintings, watercolours, prints and drawings – including works by the celebrated Glasgow Boys and the largest collection of paintings by Scottish Colourist S J Peploe outwith National Galleries Scotland! There are 53 works on display in Brushstrokes, divided between two rooms.

The layout of the two rooms is deliberately different – to trial how visitors react to these displays. Gallery Two of ‘Brushstrokes’ is an homage to the Scottish Colourists, and landscape artist William McTaggart. Here, you can see a selection of beautiful still-lives, elegant portraits and inspiring landscapes produced by Samuel Peploe, Francis Cadell, George Leslie Hunter and John Duncan Fergusson.

Some of the Scottish Colourists’ paintings on display at Brushstrokes exhibition

Gallery One, however, displays a fantastically eclectic mix of traditional and contemporary art. There are works by Elizabeth Blackadder, Anne Redpath, John Bellany, Henri Fantin-Latour, Alison Watt, Walter Sickert, Frances Walker, Joan Eardley and John William Waterhouse, to name but a few.

Eclectic mix in Gallery 1. Depicted here are 20th century works by John Houston and Marian Leven, 21st century print by Kate Downie and 19th century painting by John William Waterhouse.

In addition to trialling different layouts, we are also trialling new interpretation methods. Instead of focussing on the factual, the labels accompanying the artworks are narrative and draw attention to little details within the paintings or interesting anecdotes about the artist. Many of the works on display have been chosen by members of staff and each of these comes with an extra layer of interpretation – a ‘staff picks’ label, explaining why they’ve selected that particular painting and what it means to them.

An example of one of the ‘staff pick’ labels in the galleries. Venue Manager Helen’s favourite painting – The Old Man and the Sea by John Bellany.

We are also trying out some new ways for our visitors to interact with the artworks – QR codes that link to audio recordings with some of the local artists talking about their painting, or codes that link to more information about some of the details within the painting.

A QR code, leading to the interview with artist James Marshall Dickson is displayed next to his painting, Monument to the Michael.

To make the exhibition enjoyable for all ages, we have lots of children’s activities on offer in the galleries – games, a free activity pack, as well as our Art Cart, loaded with arty storybooks and colouring sheets.

Kids’ activities in the gallery.

To help us make some decisions about what we put in our galleries from 2023 onwards and how we interpret it for our visitors, we have built into ‘Brushstrokes’ lots of ways to gather visitor feedback, from postcards you can fill in and leave in the gallery, to Curators being around on selected dates just to chat with visitors and find out what they think about the exhibitions and what they’d like to see in future.

‘Brushstrokes’ is free so why not come along and enjoy some amazing art and help us make some informed decisions about the re-hang of the art galleries from 2023! We would love to see you and it would be enormously helpful to hear your thoughts!

_____________

This blog was written by Lesley Lettice, Exhibitions Curator and Kirke Kook, Collections Curator