As our Paolozzi elephants return to our museum stores, we take a closer look at these plastic pachyderms.

Picture the scene. Its 1970, and you’re a Scottish floorcovering manufacturer looking for a way to display brochures at tradeshows and in showrooms. It needs to be tidy, eye-catching, and chic enough to capture attention of potential customers. Obviously, the answer is to commission one of Scotland’s most influential artists to create you a series of 3000 elephant-shaped boxes.

Sounds like a leap, but that’s exactly what happened. At the time of the commission, Nairn Floors were in a strange position. They had survived the tumultuous decade of the 1960s, remaining a player in an industry that had changed dramatically. Between 1963 and 1970, a vast number of linoleum factories in Kirkcaldy had been demolished, and Nairn’s was now the only firm making floorcoverings in the town.

They had also diversified into vinyl floors, and would try their hand at carpet. As they began to diversify, they looked to consolidate their position by advertising their products to architects. These were coveted clients as, if they specified a certain brand or style of floorcovering for a large project, Nairn’s could guarantee bigger sales than they could secure with customers looking to floor individual homes. There was also the possibility that architects might come back time and time again, whereas domestic sales were – by the nature of linoleum’s long life-span – less likely to garner regular repeat purchases.

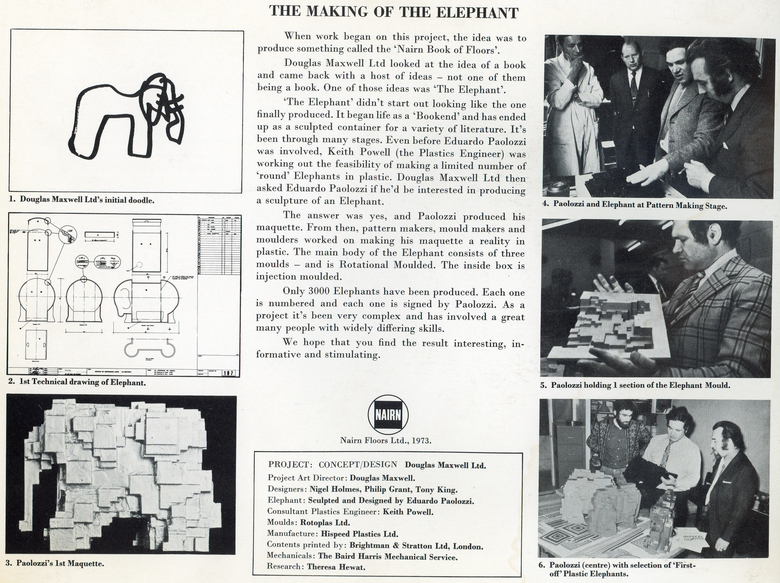

Initially, the company approached a design company called Douglas Maxwell Limited, with the idea to produce a volume called the ‘Nairn Book of Floors’. The company took the brief, and came back with several ideas – one of which was not a book at all, but an elephant. The idea was that the elephant would act as an attractive ‘bookcover’ but that the pages kept inside it could be updated as products changed.

Seems logical enough – but why an elephant? We’re a bit unclear on how that happened. Was it due to the elephantine pressure linoleum could withstand through a stiletto heel? Or perhaps the longevity of linoleums lifespan put some in mind of mammoth memories? The answer is most likely a mix of the two, supported by a universal truth: everyone likes elephants.

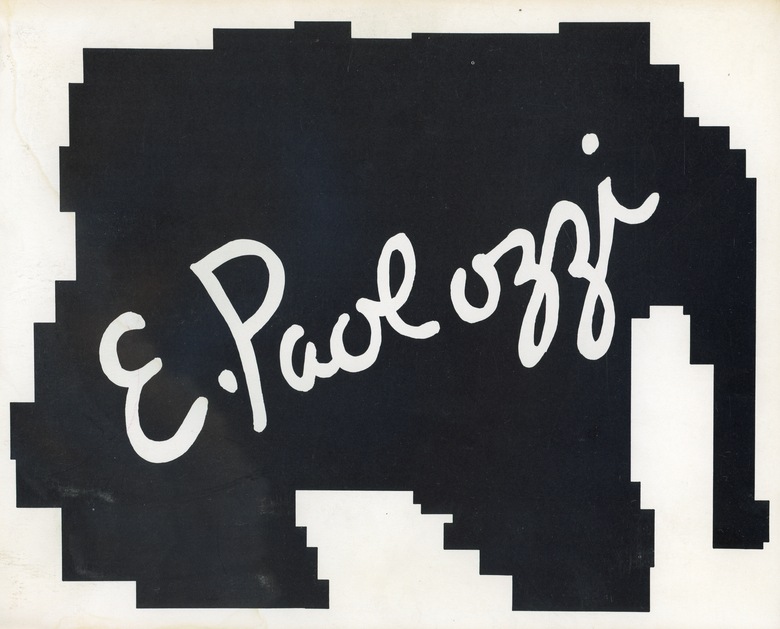

Each elephant was accompanied by a booklet explaining the design process, with Paolozzi’s signature unmissable on the front cover.

At the time, Eduardo Paolozzi was already a big name in the art world. Born in Leith in 1924, Paolozzi is considered by some to have provided a name to the era-defining Pop art movement, by including the word ‘Pop!’ in his 1947 collage If I Was A Rich Man’s Plaything. By 1972, he could boast one-man shows at MoMA, the Tate and the Scottish National Gallery (which now holds his full archive). Obviously, the next logical step was to make an elephant for Nairn’s. It seems a strange move, but of the project Paolozzi said:

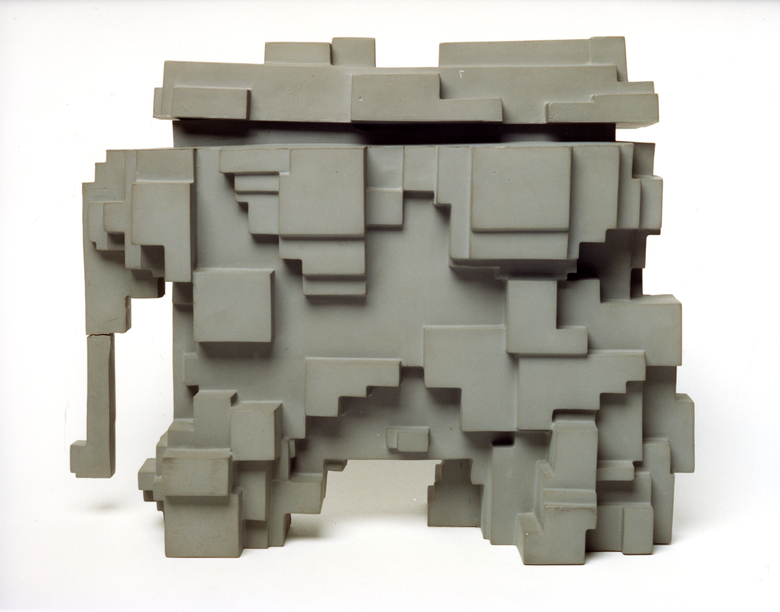

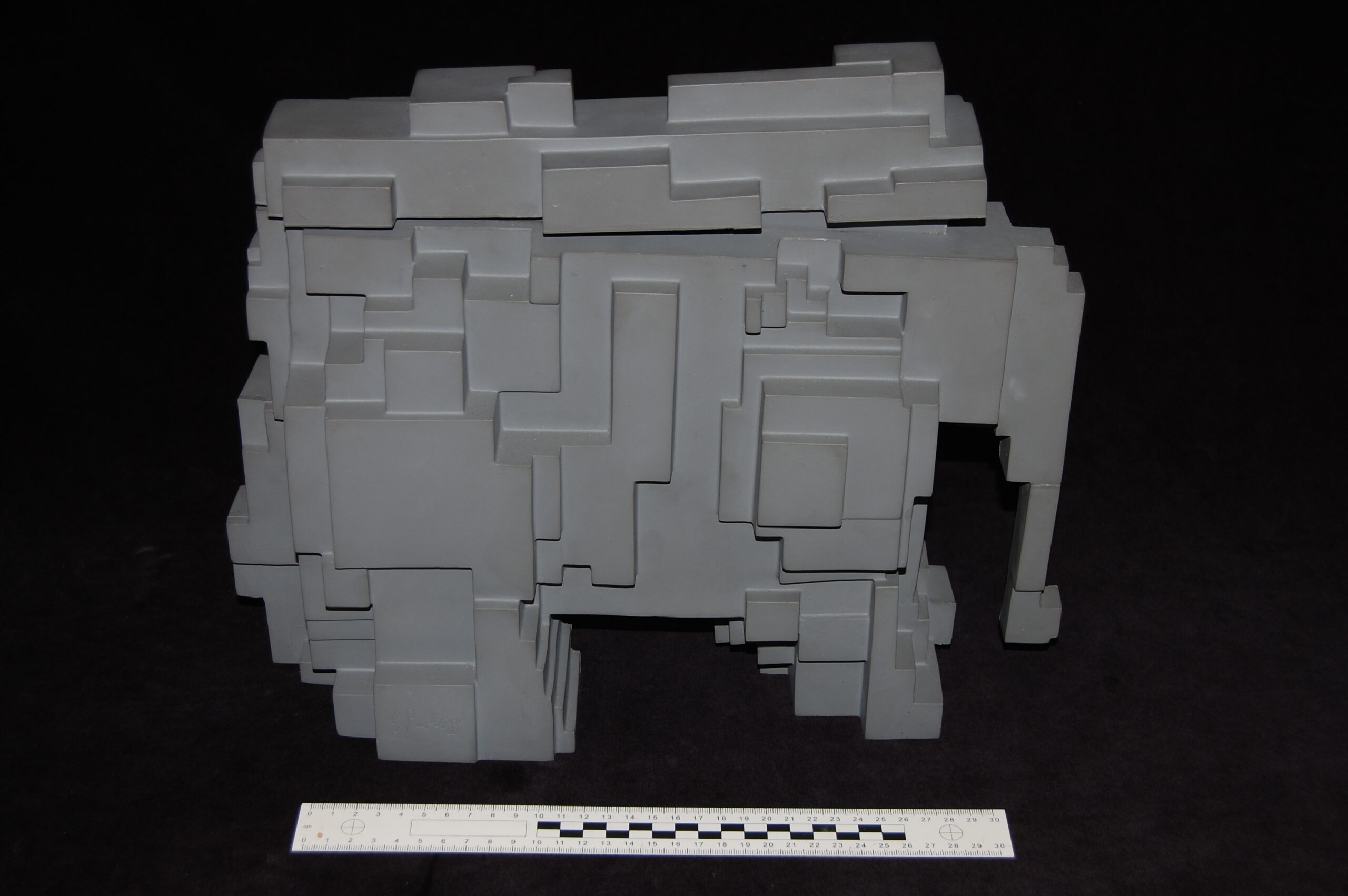

“The object was exciting to me as a sculptor. In one sense, what could be more organic than an Elephant? (Or the idea of an Elephant?). To interpret this into completely non-organic shapes, practically all geometric elements, with an emphasis on the horizontal and vertical planes, was a fascinating problem. […] I was aware beforehand of the various technical processes the sculpture would have to undergo, but found that many of the craftsmen involved were using a technology of a very fine kind, and this opened an entirely new world to me.”

The elephants – while strange and unusual to us – were inspiring to Paolozzi. They introduced him to new techniques which he would later use in his own work – most notably the Cleish Castle Ceiling.

To create the elephants, he began by producing a maquette – or model – which ‘pattern makers, mould makers and moulders’ developed into a final design. Each elephant was accompanied by a booklet which detailed the process, in which it is modestly described as “very complex”.

3000 elephants were made and, though they occasionally pop up for sale in auction houses, today only a few are accounted for. There is one in the Metropolitan Museum in New York, one in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London – and two are held by us in our Collections Store at Bankhead, Glenrothes.

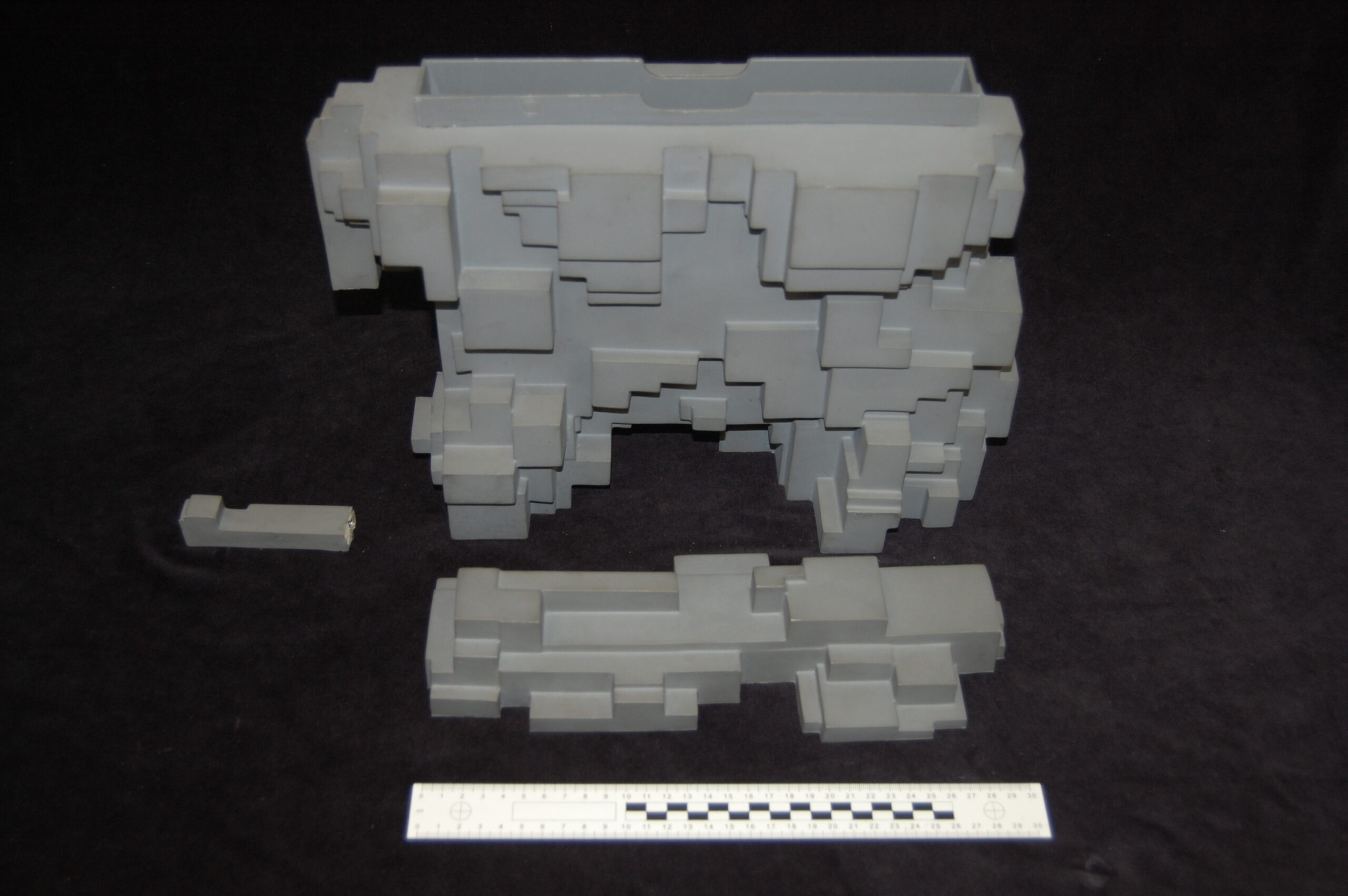

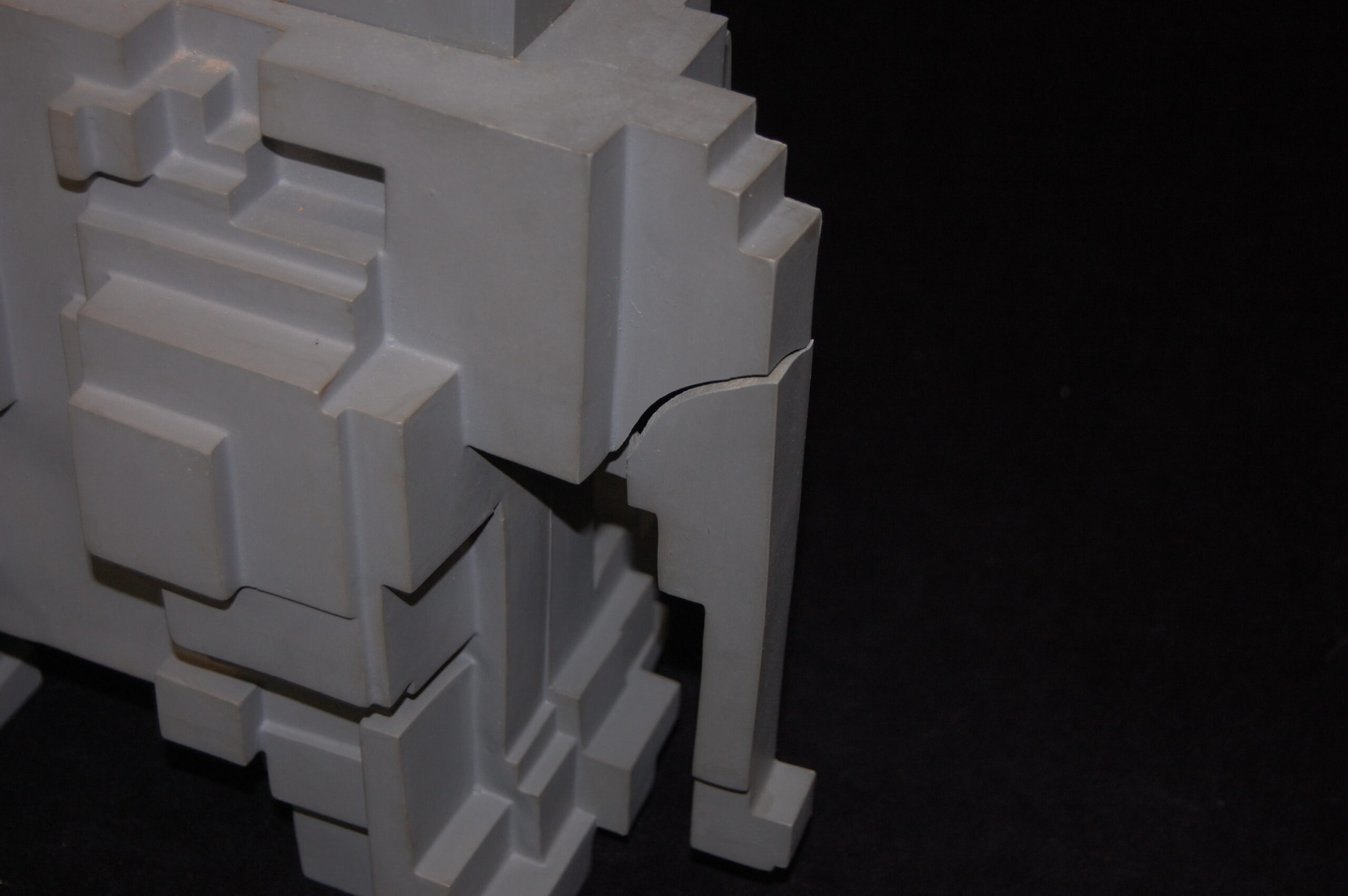

The first – marked number 768/3000 – had been with us for some time, and over the course of its life had lost its trunk. The second joined our collections this year. This one is not numbered, which may hint at it being a production proof outside of the run of 3000, perhaps produced especially for Nairn’s to keep – waiting in the archive until Nairn’s became Forbo, and Forbo chose to donate their archive to OnFife. This one had fared slightly better, but still had a few cracks across its surface.

Number 768, before conservation. KIRMG:1986.0300

While we’re all aware of the devastating environmental impact of plastic, many people are not aware of how difficult it is to preserve and care for. As it ages – which can be exacerbated by light or heat – plastic begins to deteriorate. This deterioration manifests in different ways, depending on the type of plastic; some become brittle and crack, some flake apart, some appear to melt, and most of these processes produce gasses which can damage other objects around them. On top of this, it is very difficult to tell the hundreds of different types of plastics apart. This makes care and preservation even more difficult; if we do not know what we are dealing with, we cannot tailor our behaviour to best suit its needs.

The unnumbered elephant from the Forbo Archive, with a few cracks across its surface. FIFER:2022.0235

This proved to be an issue when it came to the elephants. It was impossible to identify which kind of plastic they were made out of and, as such, the conservator could not predict how they might behave in future. Ultimately, this led to us deciding to only conserve one of them – 768. While this elephant’s trunk could be repaired using a dowel, the cracks on our unnumbered elephant would require adhesive, which could cause further damage in future if the plastic were to expand or contract. To protect both as much as possible, we opted for different treatments. Together, the pair make a perfect ‘before’ and ‘after’.

Number 768 after conservation, re-trunked and ready to go!

Our original elephant wasn’t included in the Queer-Like Smell exhibition in 1992, so the pair have yet to make their debut appearance at one of our venues. Until now! You can find the elephants at Kirkcaldy Galleries from 16 December 2022 – 8 March 2023.

Flooring the World is a two-year project exploring the history of the Fife linoleum industry. It is funded by the Esmée Fairbairn Collections Fund, which is run by the Museums Association.