From the 1950s, linoleum faced one of the greatest challenges in its history – one which influenced the way the product was marketed for decades.

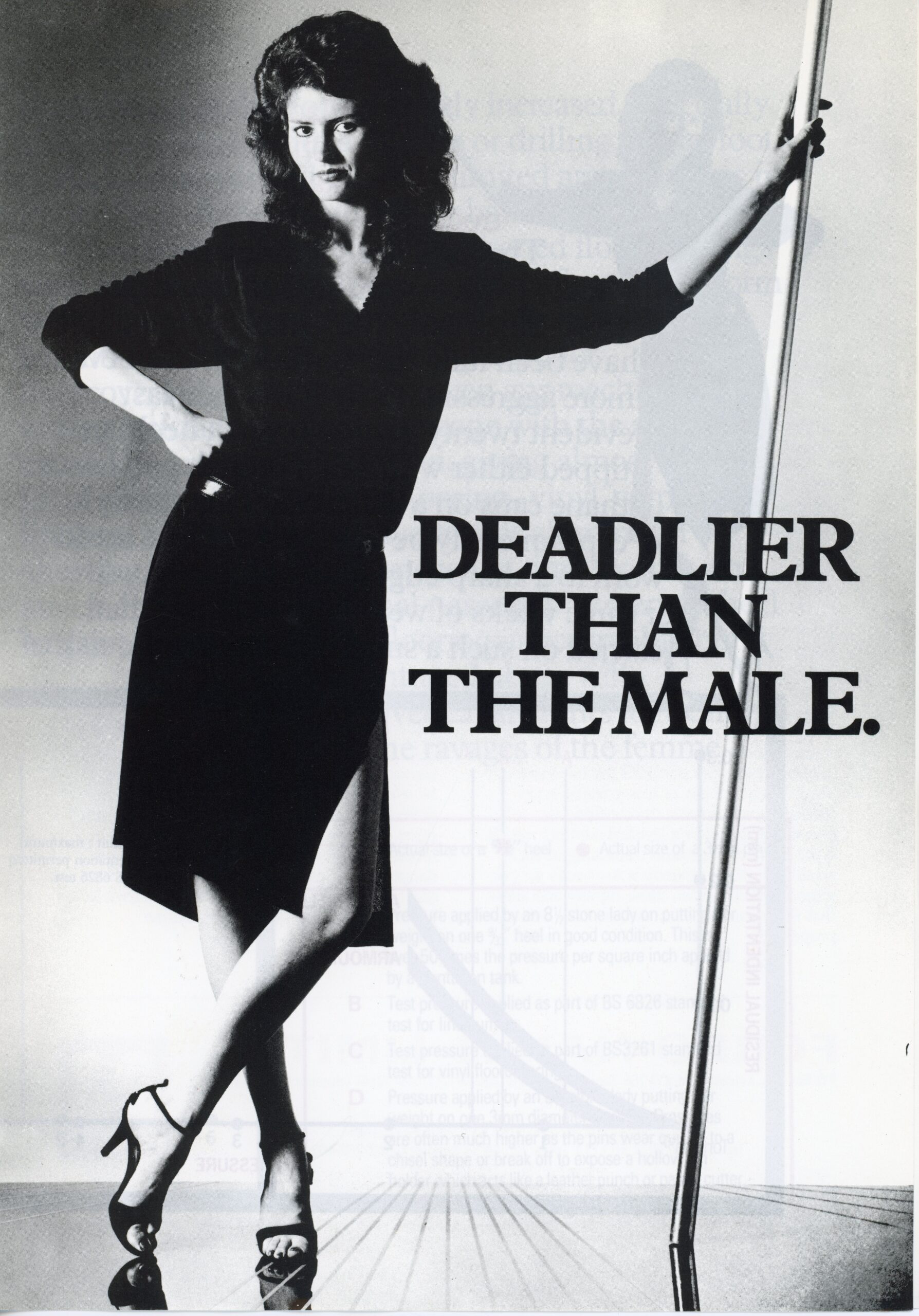

Let’s start with a image. A black and white photograph of a woman, standing in a non-descript space. Below her is a slogan: Deadlier than the male. But the words don’t refer to the woman, or to her fluffy hair, or her dark dress, or her direct stare. Instead, they’re directed at what’s on her feet: a pair of strappy, open-toe shoes with a short, thin heel.

Image: Promotional booklet produced by Forbo-Nairn, c.1985.

The stiletto heel was first developed in the 1930s, though their original inventor is disputed. The design was made possible by the use of a thin metal core within the heel which gave it its strength and structure (as well as its name – a stiletto was a thin dagger which came into use in 15th century Italy). In the 1950s, this design was popularised French designers Andre Perugia and Roger Viver. By the 1960s, the stiletto heel had spread across Europe and North America, and was synonymous with style, sex appeal and glamour.

However, the rise of the stiletto was not just a concern for the fashion conscious; in the mid-twentieth, stiletto heels were on the minds (and in the nightmares) of every linoleum manufacturer in the world.

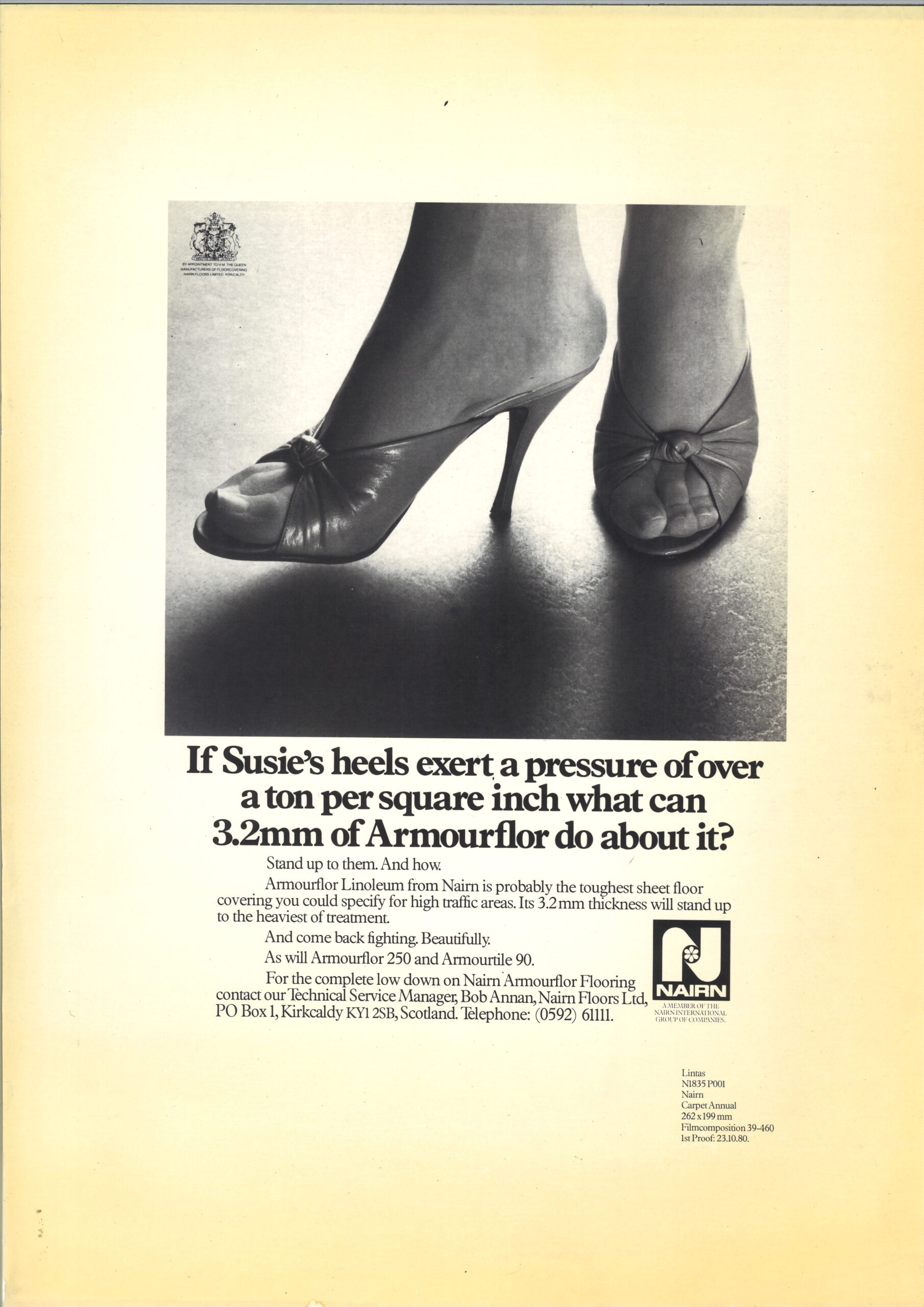

Heeled shoes had been walking over linoleum for as long as it had existed. The difference here was that the thin heel of the stiletto concentrated the wearer’s weight in a far smaller area, exerting a far greater pressure on the floor beneath. It is estimated that a stiletto heel worn by a person weighing 65kg exerts twelve times the pressure of a four-tonne elephant standing on one foot.

These high pressures meant that wearers left small indentations in linoleum floors as they walked. The increased popularity of stilettos, alongside the ubiquity of linoleum in both public and private buildings, meant that the damage was apparent to everyone. As lino’s reputation came under fire, both manufacturers and consumers became concerned about the longevity of the previously reliable floorcovering.

As such, manufacturers began to fight back with advertising. Theoretically, these stressed improvements to linoleum in the face of the new challenge of stilettos. In practice, while demonising the shoes they also laid the blame squarely at the heeled feet of the women who wore them.

Stilettos had very quickly become symbols of femininity to the point, even acting as a shorthand for signalling gender; for example, Minnie Mouse is essentially identical to Mickey, except for her high heels. Damage done by heels then, was damage done by women. Linoleum under attack from not just a shoe, but from an entire gender.

The rise in the popularity of stiletto heels came at a time when women were entering the workforce en masse. They were working in larger numbers, and in more diverse roles than ever before. At the same time as many were becoming concerned about the impact of shoes on linoleum, others were worried about the impact of this social change on the established order of things.

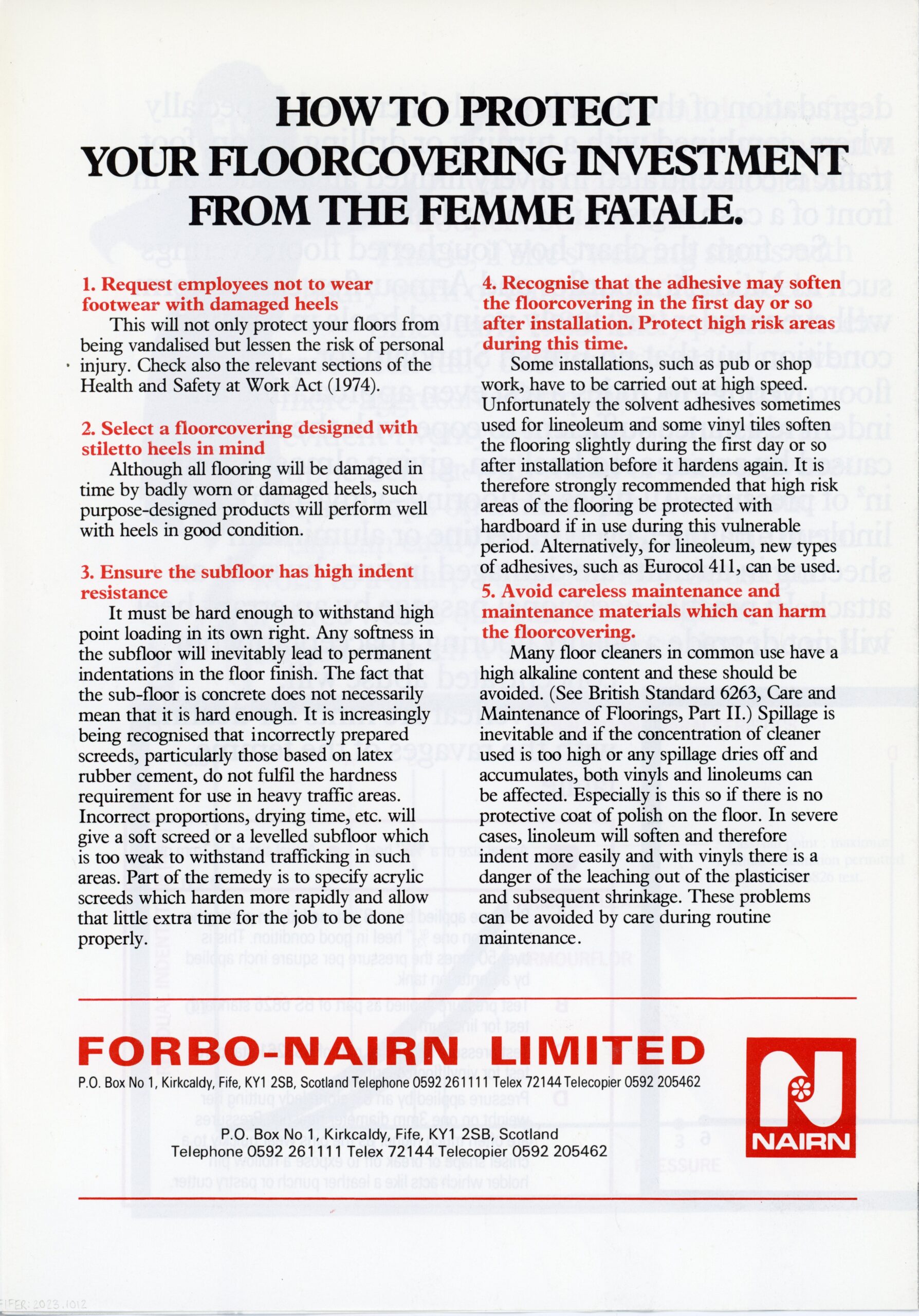

Let’s return to our advert. On the reverse, it includes a series of tips for protecting floorcoverings from the femme fatale. While most of these concern the floorcoverings themselves, the first tip simply suggests that stilettos be banned from the workplace. Dress-codes like this had been prevalent in offices since the 1950s, and were always enforced with the express desire of protecting floorcoverings. However, as stilettos had become very much symbolic of women as a whole, perhaps we can also see this trend in the context of anxieties over women’s liberation. Was the desire to have no stilettos in the workplace also partly a desire to have less women in the workplace too?

It would be wrong to suggest that linoleum advertising was in any way leading the charge when it came to sexism. However, these adverts can be seen as artefacts of a general perception of gender which – though it did not raise eyebrows at the time – now seems both dated and problematic.

________________________________________________

Flooring the World is a two-year project exploring the history of the Fife linoleum industry. It is funded by the Esmée Fairbairn Collections Fund, which is run by the Museums Association.

![]()