Throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, fire brigades were an essential part of Kirkcaldy’s linoleum industry, keeping workers, buildings and products safe from the flames.

For many of us, dialling 999 in case of fire is an automatic response. However, like centralised police and ambulance services, public fire brigades are a relatively modern affair. The earliest reference to a fire brigade in Kirkcaldy dates to the summer of 1866. They then begin to be mentioned quite frequently, so it is likely that a local service was established around then.

However, it wasn’t until 1948 that Kirkcaldy’s fire brigades were, along with the rest of the country, brought under public management. For decades, these were instead run and funded by local businesses, including linoleum firms Nairn’s and Barry’s.

There are several reasons why linoleum factories had their own fire brigades. The first was the nature of linoleum itself.

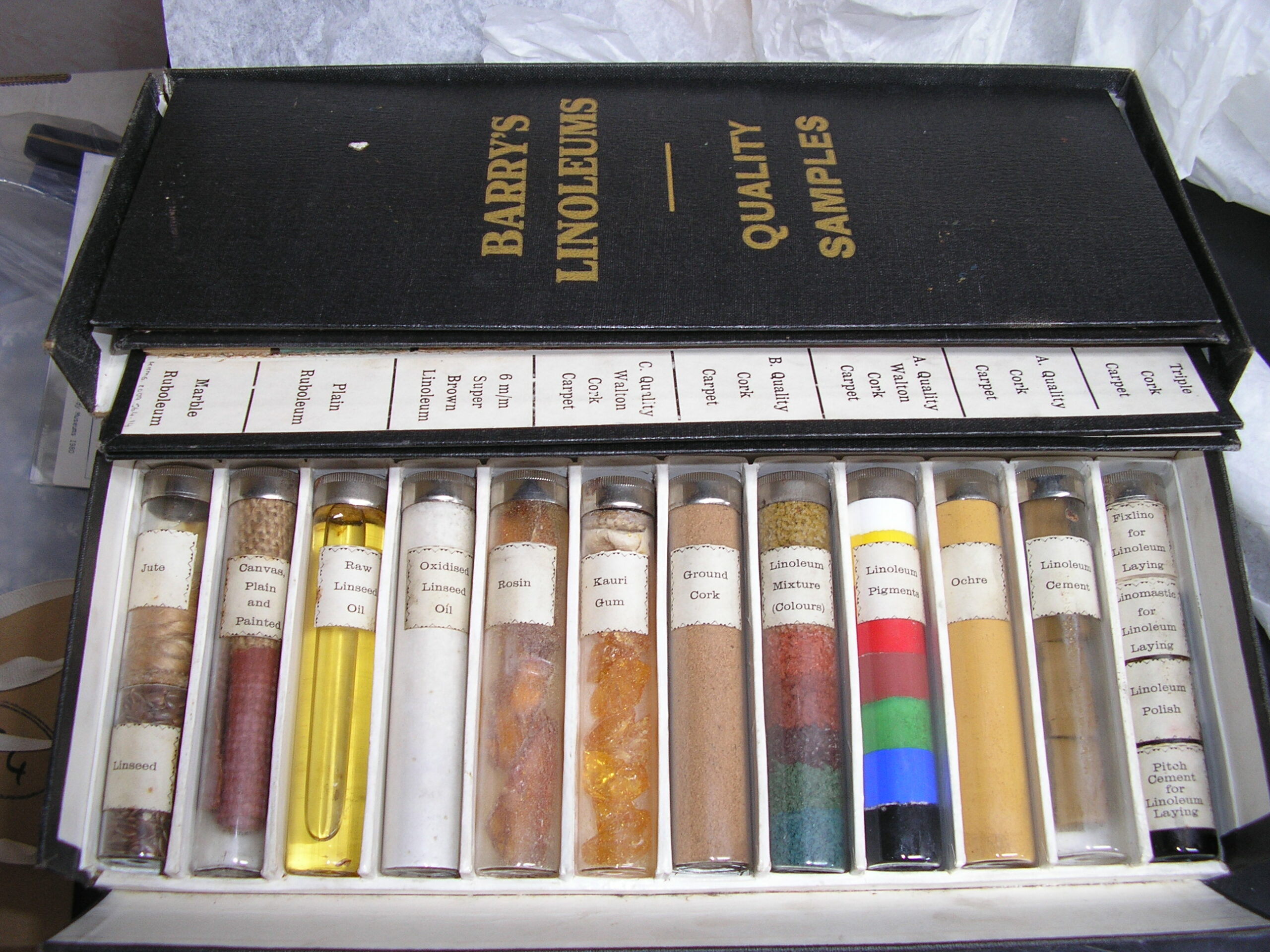

This case was carried by a travelling salesman working for Barry, Ostlere and Shepherd in the middle of the 20th century. It has several different layers which can be removed to show prospective clients different grades and qualities of floorcovering. Beneath all these are several vials which contains the materials used to make linoleum; these were largely the same when lino was invented back in the 1860s, and remain much the same today.

Many of these ingredients – such as cork, gum, and the linseed oil which gives linoleum its name – are highly flammable. They were also stored in large quantities on site. Further, heat was – and is – an essential part of the manufacturing process, with linoleum having to cure in tall stoves heated to 75 °C for 18 days. Add to this the heat generated by running machinery, and the whole thing starts to look very risky – for buildings, any finished products and, most importantly, for the workers themselves.

Having firefighters on site meant that emergencies could be dealt with as quickly as possible, reducing damage and danger. Later, it also had the added cost benefit of reducing insurance premiums; the sooner blazes could be neutralised or the more they could be minimised, the less it would cost the insurer in damages.

The dangers of linoleum manufacture were universal. Beyond Kirkcaldy, Nairn’s also employed in-house brigades at their factories in France. 1911.

Beyond the practical, there were also less tangible benefits for both firms and workers.

Factory fire-brigades were also another opportunity for linoleum manufacturers to show off and popularise their ‘brands’. Just like factory bands and sports teams, fire-fighting was a visible part of civic life, which allowed them to put their best foot forward. Fire-fighters might march in parades, or attend public ceremonies – all promoting the idea of their factories as dependable, resilient and the subjects of pride.

The Nairn’s fire brigade. c.1910.

Linoleum manufacturers certainly took care to make sure that there could be no mistaking which fire brigade belonged to who. In the photograph above, you can see the Nairn’s thistle logo above the fire engine; a similar logo now exists in our collection. This one dates from the mid-20th century, but would have fulfilled much the same purpose. From the 1970s onwards, workers at Nairn’s also took part in competitive fire drills – which were kind of like sports days with foam extinguishers. A wooden thistle logo was always there, at the foreground of any photo-opportunities!

These were opportunities to socialise, put on a show and to compete against other factories and industries. From the 1860s until the late twentieth century, fire-fighting allowed linoleum workers to be a part of the fabric of their communities – both within and without of the factory walls.

Today, there is still a fire engine on site at the Forbo Factory – a 1973 Ford Transit 125 Custom with 10329 miles on the clock. It’s used to carry out the fire teams weekly site inspections and is used to assist the emergency services if they are ever called to the factory site. Thankfully, it’s been over five years since this classic engine was needed.

If you would like to see more objects associated with factory fire-brigades, you can see our new temporary display in the linoleum case in the Moments In Time gallery, Kirkcaldy Galleries. Like all of our permanent displays, it’s free! You can see it until the middle of January, when we’ll change it to share another aspect of the research carried out during the Flooring the World project.

Flooring the World is a two-year project exploring the history of the Fife linoleum industry. It is funded by the Esmée Fairbairn Collections Fun., which is run by the Museums Association.

![]()