Fife in Lockdown: collecting future history

Like many other museums all around the world, the OnFife team set out to create a permanent record of the difficult times we all experienced during the first two years of the Covid-19 pandemic. Although still fresh in our minds, the pandemic will one day become an important section in history books. Our museums’ Collections team has therefore collected objects and archival material linked to Covid-19, including a self-test lateral flow kit, a face covering, and a bottle of hand sanitiser produced by a local distillery.

In addition to that, we also set out to record individual Fifers’ thoughts, feelings, and experiences around what they were going through. This material has now been processed and compiled into our “Fife in Lockdown” digital archive.

On 26 March 2020 OnFife started a campaign, inviting individuals to email their lockdown experiences to the museums’ Collections service. In addition to that, our colleagues from the Exhibitions team, Local Studies, Archives, Creative Development, and Young People’s Service helped us spread the word about this project through their networks. Here are some examples of what we collected.

Documentary images

We were sent an array of photographs of various signage and imagery we became familiar with during Covid. The signage reminded us to stay safe, keep our hands clean and sanitized, and keep our distance from others. Variations of these signs were used all around the world – which is a mind-boggling thought! I wonder what memories these images will evoke in 10-, 20- or 50-years’ time?

Photos by Jennifer Kelly

Another iconic group of images we received were linked to the NHS. Including photos of the NHS rainbow – a symbol of resilience and hope.

Photo and text by Niamh Conlon: “This bench was created by one of our neighbours. It was taken during lockdown on one of our once-a-day walks. We were lucky in that we had access to green space”.

From communal support for the NHS to isolation – those who had to spend time at a hospital during the pandemic often found it a lonely experience.

Photo and text by Clare Whiston Fisher: “Due to COVID issues in hospital I could not be accompanied in the ambulance by a family member and wasn’t allowed visitors”.

Photo, painting and text by artist Katy McKidd-Stevenson: “I saw Emma’s (a cardiac scientist) photograph on social media, her selfie which she took showing the marks left by the masks she had to wear on the ward for Covid safety – I loved her poor wee face, and wanted to paint it, so I contacted her and asked her permission, which she gave”.

Diaries

Many Fifers were kind enough to share their lockdown thoughts and feelings with us, spanning from a couple of paragraphs to hundreds of pages. Here are some snippets from them. Which one of these experiences do you most identify with?

“Was able to buy yeast again today. It has been impossible to find for at least a couple of weeks; it’s odd how little things like that assume such importance in lockdown conditions.”

“Working from home, never used TEAMs before. What is it they say about monkeys left in a room with a typewriter?”

“There is some value in an ‘all in this together’ feeling and it’s likely that some at least of the beleaguered and courageous NHS staff gain strength from the visible (audible) expressions of support. I can’t pretend to be comfortable clapping on the doorstep in the twilight – but who says we have to be comfortable?”

“Early on, people started colouring rainbow pictures and putting them in their windows for people to see. It helps us to feel less isolated…knowing we are all going through this together.”

“My next-door neighbour often puts our bins out in time for collection day. I thanked him today and explained that I’d only brought mine back in because I’m wary of touching anything that’s not mine. It feels ridiculous to not be able to touch the handle of his bin to pull it back up to the house.”

“I’ve become a little bit of a therapist for some of my friends, who are feeling a little depressed during these times.”

“I put on my happy face as I didn’t want the kids seeing me like that. Mums are meant to be strong and here I was weak. I also developed a guilt over feeling like this as here I was feeling like this safe at home when there were people out there risking their lives for others. I did feel better when I was up and playing games with the kids or watching movies with them but once they were in bed, I started to feel depressed again.”

“At home, we are feeling a kind of cabin fever, sitting down every evening to supper and then choosing a film or TV series to watch. It feels like Groundhog Day without the possibilities of improving on what went before. I’m missing weekends away and feeling refreshed by a new set of experiences.”

Helping others

During lockdowns, many of us lent a helping hand in our communities. Here are some examples:

Photo and text by Sylvia Scott: “The scrubs were sewn for the NHS early on in Lockdown, almost all the ones that I made were from recycled fabric and all triple washed at 60 degrees prior to being worn. They went to NHS doctors, and some were brightly patterned”.

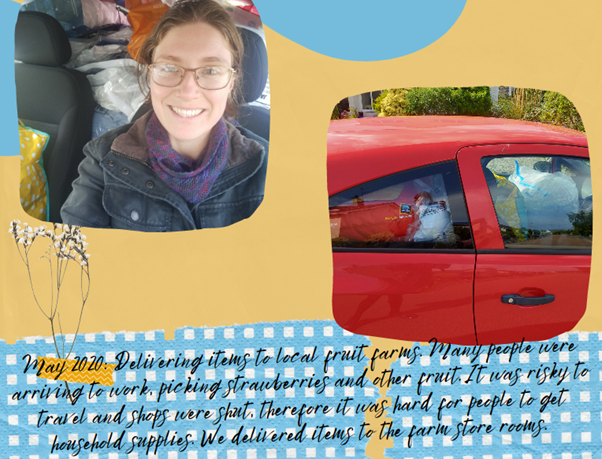

Delivering food and other essentials to neighbours and local organisations in need will also bring back memories to many. Here is a photo of Becky and Gideon’s car during one of their delivery runs!

Image by Becky Salter

Creative projects

Lockdown gave many people an opportunity to focus on hobbies or even start a new one.

For example, spending time in the garden:

Photo and text by Robin Arnott: “As they say, “every cloud…” and I decided that I needed a project to keep me active. With a large cactus and succulent collection, May and June are prime flowering months for the cacti but being often away in the caravan at that time meant that I missed seeing many of the wonderful blooms. My project in 2020 was to photograph every plant as it came into bloom and undertake some botanical research into their origins”.

Photo and text by Marjory Archibald: “Self-isolating since March 18 meant that our dependency was on caring neighbourhood and using technology. Indebted to both of these my contribution to your Project is a series of photographs sent daily by my neighbour Alan whose career was in Horticulture. Each morning a treat of spring flowers arrived on WhatsApp. Depicted here is the first bumblebee of the season on Camellia Debbie. 18 March 2020”.

Crafting or painting:

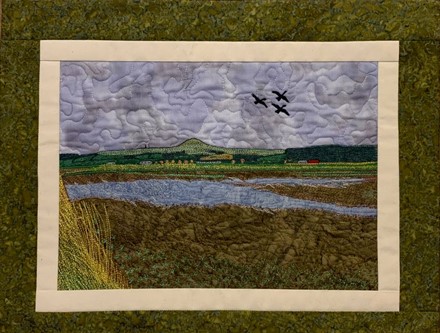

Photo and text by Andrea McMillan: “I live in Auchtermuchty and there is a community shop in the next village, Dunshalt, that does a great take-away latte. I got into the habit of walking over once a week, across the fields and back along the road. That’s about 3 miles and I felt I earned my coffee and cake. There are great views over the Howe of Fife towards the Lomond Hills, and I took a photo in October 2020 of waterlogged fields. This is the result; the three birds are Pink-Footed Geese which we see in their multitudes at this time of year. The water on the field is a stitched sheer fabric”.

Photo, painting and text by Margaret Cummins: “I was beginning to feel that the inconsistent rules had overtaken my life! Sometimes so ludicrous they were funny! So, I painted this picture of a pink elephant, a pink and green owl with some poppy seeds and leaves hanging upside down and socially distancing themselves…”

Or writing short stories and poetry:

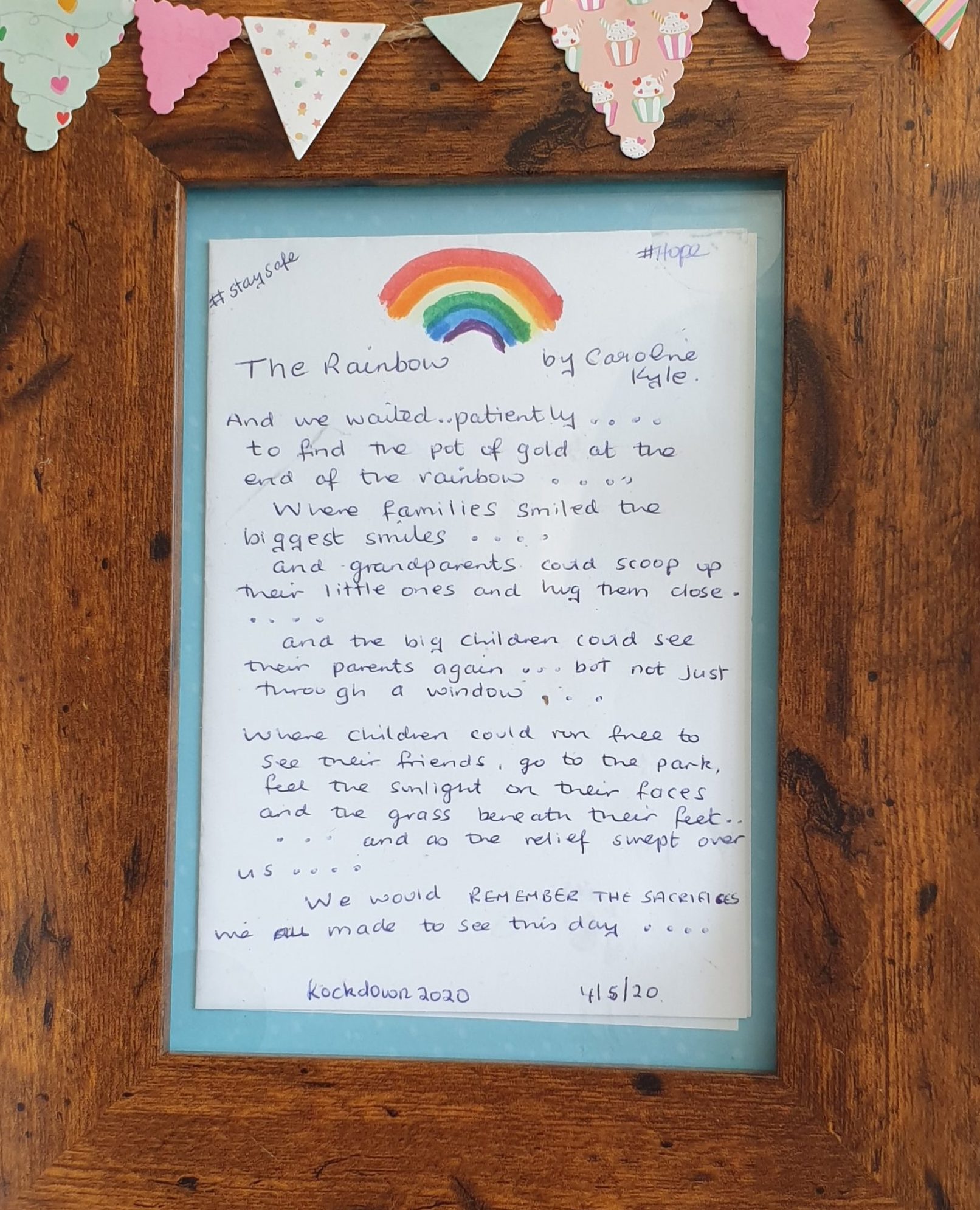

Photo and poem by Caroline Kyle

The Fife in Lockdown archive is currently not publicly accessible but is permanently saved on our Collections Management System to be used in future exhibitions and research.

We would like to thank all participants: Marjory Archibald, Robin Arnott, Ann Bain, Martin Boyle, Margaret Braid, Niamh Conlon, Julian Crowe, Margaret Cummins, Judith Dennis, Fife College students, Clare Fisher, David Hughes-Hallett, Bernadette Kelleher, Peter Kellett, Jennifer Kelly, Catherine Kerr-Dineen, Caroline Kyle, Eunice Lacey, Penelope Lycett, Katy McKidd-Stevenson, Andrea McMillan, Linda Menzies, Gillian Paterson, Donald Payne, Lindsay Proven, Becky & Gideon Salter, Maureen Sangster, Sylvia Scott, May Smith, Eileen Louise Walls and those who wished to remain anonymous.

Your contributions will become history!

______________________________

Call-out for additional participants

We are still looking to add the following memories to our Fife in Lockdown database:

- Experiences of a first-time mum

- Wearer of a sunflower lanyard

- Individuals or those working with individuals for whom English is not their first language

If you wish to submit an entry, please email lockdown@onfife.com before 22 August 2022.

This blog was written by Kirke Kook, Collections Curator

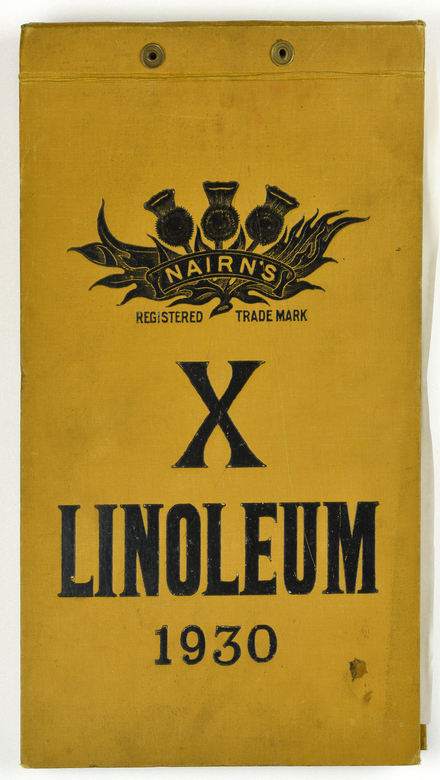

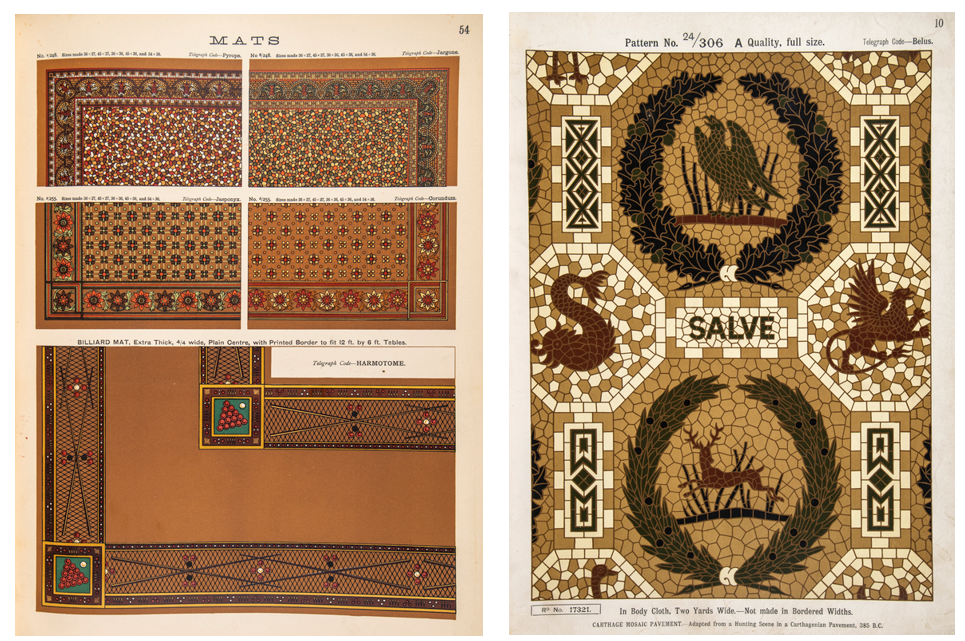

Image: A pattern book. KIRMG:1992.0267

This is a pattern book, produced by Nairn’s of Kirkcaldy in 1930. It contains full-colour images of the linoleum designs produced by the company in that year, and would have been made available for customers to browse before they made their selection.

We have over fifty of these in our collections, dating from the mid 19th century to the 1960s. As we continue to accession the Forbo Factory archive, modern brochures join this collection to allow us to view linoleum as potential customers have for 150 years. While the way in which linoleum is made has changed little in that time, the styles sought after by and available to customers have changed dramatically.

20th and 21st century designs tend to be more general in their function; today, Forbo brochures showcase marbled-pattern linoleums in a kaleidoscope of colours, fit for every style and season.

However, our 19th century pattern books contain designs created with specific spaces in mind. One features a border of cues and billiard balls for a games room, and the inclusion of the word ‘Salve’ (the Latin for ‘welcome’) in this classical design points towards its being intended for an entrance hall. The room in the house which seems to have generated the most elaborate space-specific designs, however, is the nursery.

Images: Two pages from FIFER:2022.0150.

Today, we associate linoleum in the home mainly with kitchens and bathrooms; in the 19th and early 20th centuries, it (along with its forerunner floorcloth) could be found in any room. So, with all these rooms to choose from, why designs intended specifically for the nursery? This trend was dependent on two key social developments in the late Victorian period. The first, as strange as it sounds, was the invention of childhood.

Prior to this time, the common consensus was that there was nothing special about being a child. Children wore miniature versions of adults’ clothes and contributed economically to the family by working. They were seen as miniature versions of the grown-ups they would become – with any variations from adulthood being seen as passing nuisances.

In the mid 19th century however, improving economic conditions and the rise of the middle-classes meant that it was not always essential for children to work to support a household. Life before adulthood became associated with leisure, play, and innocence. Rather than a temporary state of smallness, childhood became something to be cherished and protected.

Image: Portrait of Ian Couper Nairn, by Harrington Mann. KIRMG:383. The children of the Nairn family – Kirkcaldy’s original linoleum manufacturers – had their portraits painted in 1899. They would’ve been among the first generations of children raised according to new notions of childhood. In this portrait, we see Ian Couper Nairn standing in an interior – perhaps a glimpse into his linoleum floored nursery?

This same economic improvement brings us to the second change: a greater separation between work and the home.

Due to British imperialism, this period was marked by accelerated industrialisation. As the shape of work changed, so too did the shape of the workplace. Towns and cities across the country became filled with factories and warehouses – transforming raw materials and storing finished goods extracted from overseas territories – and offices to manage these global businesses. Britain grew rich by travelling beyond its shores, exploiting the people and lands of its acquired territories. As a result of this, middle-class families were able to mirror this expansionist impulse, travelling beyond their homes to new, modern workspaces.

On a practical level, this meant that many middle-class Briton’s now found themselves with more space in their houses. So, as childhood became a precious, protected time in a person’s life, the home became a special place reserved for leisure, relaxation and the family (though each of these privileges was dependent on being born into a family wealthy and stable enough to afford them). The extra space in the home therefore naturally became a place exclusively reserved for children: the nursery.

This meant that there was suddenly a new market to be catered to. However, the idea that children will have at least some say in how their spaces are decorated is a relatively new one. So – while children would undoubtedly have enjoyed them – these patterns were primarily designed to cater to the adults who would be purchasing them.

More specifically, they appealed to women. Though men’s work had left the home, women’s labour remained. As the home began to change shape (and size) in response to these social and economic changes, a new task emerged for the middle-class Victorian – the creation and cultivation of a tasteful interior.

Whereas once, home furnishings beyond the functional and comfortable were the preserve of the upper-classes, middle-class homes were now also expected to be finished in the latest fashion. From the 1860s, ‘homemaking’ became a respectable pastime for well-to-do women, joining the ranks of other sanctioned hobbies such as album-making, crafting faux flowers, and fern collecting. Each of these hobbies was seen as distinctly feminine, and as exercises by which women could cultivate their finest ‘womanly’ traits and, by extension, their morality. They required quiet, rewarded perfectionism and patience, and encouraged the contemplation of the meek and delicate.

Homemaking fulfilled a similar function, but with a crucial difference. Whereas these other crafts resulted in small, hidable products, home décor was a comparatively public medium for self-expression – or, more accurately then as today, an expression of the self one wished to impress on others. An ill-pasted page in an album could be avoided; an unkempt, poorly appointed room was for all to see.

Alongside creating a home which was fashionable and comfortable, therefore, the middle-class Victorian woman also had to make sure her home décor choices conveyed her unblemished character. This meant, of course, that it had to be clean.

In the 19th century cleanliness was truly next to godliness; any evidence of dirt or wear was surely a sign of loose character. Here then, the Victorian woman was in a bind. To be a ‘good’ wife, it was expected (perhaps even necessitated in an era with paltry access to contraception) that she have children. However, that goodness would be easily undermined by mess which naturally accompanied those children. The solution to this problem was – you guessed it – linoleum.

Images: This advert for Forshaga linoleum (left; FIFER:2022.0201) touts the floorcoverings virtues in relation to the body of the housewife. In Kirkcaldy (right, TEMP:2011.4263), a slightly different tactic was used to emphasise linoleum as a labour-saving innovation. This advert by Nairn’s impresses that its products are dry-wipe using the cute metaphor of puppies and kittens rather than the unpleasant reality of the messes all young animals – including nursery-bound humans – make.

The hygienic qualities of linoleum have always been central to its appeal, and the same was true in the 19th century. Linoleum was quicker and easier to clean than traditional floorcoverings, and this was exploited in adverts, such as this one produced by Swedish manufacturers Forshaga.

The stress of cleaning a wooden floor is obvious in the face of the woman scrubbing them who – with her muscular arms and messy hair – is coded as working-class. The leisured middle-class homemaker on the right does not have to spoil her appearance or her delicate, idealised figure with such labour: she has linoleum. Linoleum, therefore, was a good and proper thing for Victorian women – indeed, it would help them preserve their status by ensuring that their homes and bodies conformed to class and gender norms.

If dirt and mess was a visual sign of moral decay, noise of any kind warned the ear of bad character. Here too, linoleum had the edge over wooden, stone or tiled floors. Linoleum – particularly thicker and more expensive varieties such as cork carpet – muffled the sounds of toys bounced, dragged or skittered across it (while also resisting any marks they might make). It was also more forgiving on toddling, crawling bodies – which (theoretically) meant less crying. Childhood was precious – but children were still meant to be seen and not heard.

Once a Victorian woman was certain she had a clean and moral home, she had to turn her mind to the future – and that meant education. It was up to her to impress both knowledge and upright values on her young charges – and linoleum – it was hoped – would shape the futures of the small humans who walked on it.

Image: This cork carpet design, dating from 1892, shows children playing in an imagined countryside. At a time when the industrialisation which made floorcoverings like these and the nurseries which housed them possible, there was a strong popular taste for images of a rural life which was imagined as simpler and more innocent than modern cities – just as childhood became seen as simpler and more innocent than adulthood. FIFER:2022.0174

The floorcoverings designed for nurseries served as teaching tools as well as decoration. Writer Samuel Smiles stressed the importance of visible examples of good behaviour, insisting that these were far more impactful than mere explanation. More was at stake than just a peaceful homelife; for Smiles, “the nation [came] from the nursery” – the health and strength of the country depended on children knowing clearly what was expected of them.

To do this, floorcovering designs borrowed heavily from other media created with children in mind. Illustrated books produced by English artists Kate Greenaway and Walter Crane clearly had a strong influence on the designs in our collections.

The design above clearly mimics Greenaway’s style. It epitomises the idealised childhood of the time – well-behaved, flaxen-haired children frolic unsupervised in a colourful, pastoral idyll. Their world is unblemished by signs of work or modernity; their play is neat and innocent. Children surrounded by these designs surely could not help but follow their example, as Smiles hoped.

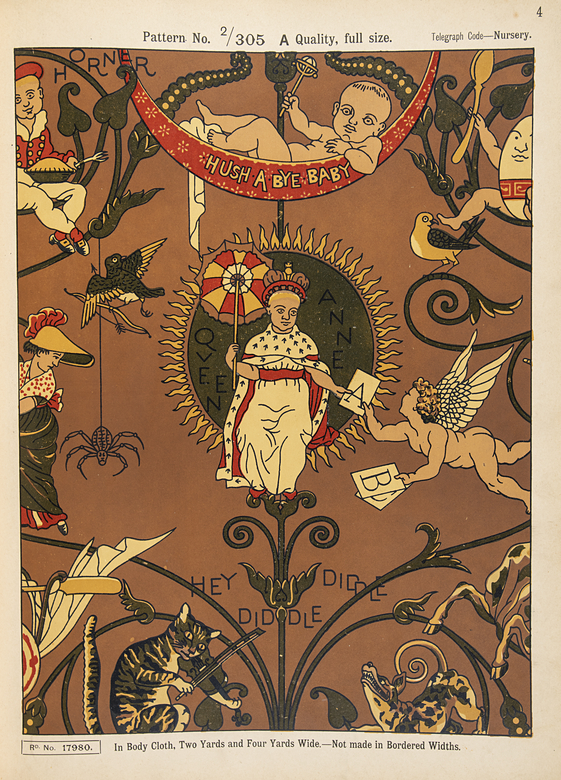

Image: In a pattern book produced by the Kirkcaldy Linoleum Company, 1876 – c.1900. Though the colours differ from Crane’s wallpaper, the rest of the design is identical. Though most of these nursery rhymes have stood the test of time, the central song ‘Letters to Queen Anne’ appears to have faded away from the nursery in the 20th century. FIFER:2022.0150

Another theme favoured by interior design writers, consumers and manufacturers alike was nursery rhymes. This design by Walter Crane was commissioned by Jeffrey and Co. in 1876; examples of this paper – both in a predominantly blue and yellow colour scheme – survive in the collections of the V&A and the Cooper Hewitt Museum. We don’t know exactly when it was adapted by the Kirkcaldy Linoleum Company, but the fact that it was is testament to its popularity.

Pictures in rooms used by children served the same purpose then as they do now: to provide bright and colourful memory aids to assist learning and lend rhythm to group games and activities. Children living in industrial cities might not venture into a Greenaway-esque countryside, but they would still learn to tell a cow from a spoon in a well-appointed Victorian nursery, as well as maybe learning a bit of the alphabet.

All of this together meant that, from the mid-19th century, the physical reality of the Victorian home – its fixtures, fittings and decoration – was seen as an essential to the moral, intellectual, and physical health of the nation and its Empire. While the interior home was important, this project started from the bottom up – both in terms of beginning in childhood, and beginning with an appropriate floorcovering. Given the high stakes, is it any wonder linoleum companies designed products specifically for the nursery?

_________

This blog was written by Lily Barnes, curator working on the linoleum project Flooring the World (2022-2024). Flooring the World is a two-year project exploring the history of the Fife linoleum industry. It is funded by the Esmée Fairbairn Collections Fund, which is run by the Museums Association, funding projects that develop collections to achieve social impact.

If you have any questions or information you’d like to share, you can get in touch at lino@onfife.com

In the 19th century, the people of Staten Island seemed to have had a liking for names which were simultaneously on-the-nose and industrial. The establishment of a major manufacturing plant in 1819 gave its name to the town of ‘Factoryville’, nearby quarries to ‘Graniteville’, and the Kreischer brick works to ‘Kreischerville’. It is perhaps therefore little surprise that, when the American Linoleum Company began production in 1875, the town which grew around the factory became known as Linoleumville.

This photograph shows two men standing in a shop in Linoleumville, c.1900. It is brimming with patterned linoleum, and an example of a linoleum ‘mosaic’ (like this one in our collections) is visible to the right. Image from the collection of Historic Richmond Town.

The American Linoleum Company had been formed in 1873 by two Yorkshiremen – John Crossley and Frederick Walton. Crossley was an MP and carpet manufacturer, who saw the promise of manufacturing floorcoverings in North America to consumers who were currently ordering products from British firms. By removing shipping costs, the American Linoleum Company would be able to offer a cheaper rate than their competitors on the east of the Atlantic, and dominate a ready-made market.

However, this market was for linoleum, rather than carpet. That was where Walton – the inventor of linoleum – came in. Walton had had mixed success with this new material in the United Kingdom. Linoleum had proved wildly popular, but Walton lost control of his invention by failing to trademark its brand name; it was due to this lapse that Kirkcaldy firm Michael Nairn and Company began making and selling the product. Nonetheless, Crossley viewed Walton’s knowledge of the product and manufacturing process as invaluable, and the latter set about preparing the Staten Island site for two years prior to beginning to production.

All this preparation paid off, and the Staten Island factory was initially extremely successful, so much so that it struggled to fulfil demand as orders from eager buyers poured in. In 1882, the factory became the first building in Staten Island to install electric lighting in order to allow for a night shift to maintain a busy production schedule. This enabled the business to continue to grow – in 1886 alone the plant produced over 1 million square metres of linoleum.

In that same year, Michael Nairn and Company Of Kirkcaldy chose to join the booming American market, and opened a factory in Kearney, New Jersey. Nairn’s products were similarly in demand, but the New Jersey site was less than a quarter of the size of the Linoleumville works – perhaps this was why Kearney kept its name, despite some dubbing the town the ‘linoleum capital of the world’.

Office staff of the Nairn’s factory in Kearney, New Jersey. KIRMG:1983.0597.

The huge scale of production in Linoleumville meant that the American Linoleum Company works soon became a key employer in the area. The town that had sprung up beside the factory continued to grow as business boomed. The industry attracted European immigrants, predominantly from England and Poland. By the turn of the 20th century, approximately 700 people were employed at the factory – approximately half the town’s population.

This photograph by Willard D Decker shows the factory at 12 noon, c.1900. The high brick chimney to the right was a feature of many linoleum factories – the chimney of the St John’s Works in Falkland stood above the town for decades before it was demolished in 2017. Image from the collection of Historic Richmond Town.

Without linoleum, it is possible that few if any of these workers and their families would have settled in the area. Far from being merely the product which gave the town its name, linoleum was the reason for Linoleumville’s very existence – and its continuing survival.

However, by the late 1920s, the business had began to decline. In 1930, the factory closed, meaning that Linoleumville was now to be without its namesake for good.

The economic and emotional impact of the factory’s closure hit the townsfolk hard. When, in 1931, the townsfolk held a vote to change their towns name, the New York Times reported that only four “old timers” voted to keep Linoleumville, stating that it “had an honourable record”. Presumably, the rest of the town did not feel the same, and their home was shortly re-christened Travis after a Colonel who had been involved in the initial colonisation of the area.

_________

This blog was written by Lily Barnes, curator working on the linoleum project Flooring the World (2022-2024). Flooring the World is a two-year project exploring the history of the Fife linoleum industry. It is funded by the Esmée Fairbairn Collections Fund, which is run by the Museums Association, funding projects that develop collections to achieve social impact.

If you have any questions or information you’d like to share, you can get in touch at lino@onfife.com

This February, we began work on Flooring the World – a two-year project exploring the history of the of linoleum production in Fife.

Linoleum has been made in Fife since soon after its invention in the 1860s up until the present day, with production centred in Kirkcaldy, Newburgh and Falkland. It has changed the shape of the entire county, and of the people who live within it, and today Kirkcaldy is the only place in Britain where linoleum is still made.

Workers inspecting linoleum production, Newburgh. CUPMS:1986.809.

As part of this project, we are interested in establishing connections and beginning conversations with those who have experience of working in the linoleum industry. If you currently work, or if you or your family members once worked, in the Fife linoleum industry – we want to hear from you!

We’d love to hear any memories you have to share, but here are some ideas to get you started:

- Can you tell us about your day to day working life?

- Do you have a memory of a specific day at work which has stuck with you? This could be your first day, your last day, a day you received some exciting news, or even just an ordinary day which has stayed with you.

- Which aspects of your work stayed the same during your time working with linoleum? What changed?

- If you could share only one memory of your working life, what would it be?

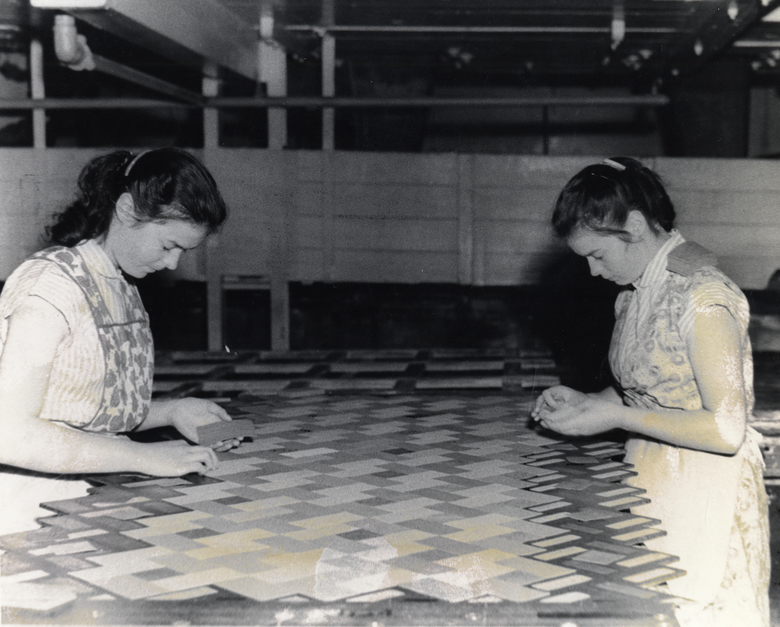

Women workers making inlaid linoleum, Kirkcaldy, c.1960. TEMP:2012.4423.

We are interested in all aspects of working in the linoleum industry – any role, any length of service, at any time, in Kirkcaldy, Newburgh or Falkland – and would particularly welcome information relating to:

- The experiences of women in the workplace

- The experiences of workers who were employed in the linoleum industry from 1960 onwards

- The experiences of those involved in social activities such as work bands, clubs and sports teams

- The experiences of workers involved in industrial action, such as strikes and protests

Alternatively, if oral history isn’t for you, there are other ways you can get involved. If you have an object you’re considering donating to our collections, if you’d like to learn more about upcoming volunteer projects, or if you’d like to share some information or ideas for future research, then we’d love to hear from you too!

You can get in touch with Lily Barnes, the Project Curator, by sending an e-mail to lino@onfife.com

Block-cutters at Barry, Ostlere and Shepherd, Kirkcaldy, 1952. KIRMG:1976.603.

_________

This blog was written by Lily Barnes, curator working on the linoleum project Flooring the World (2022-2024). Flooring the World is a two-year project exploring the history of the Fife linoleum industry. It is funded by the Esmée Fairbairn Collections Fund, which is run by the Museums Association, funding projects that develop collections to achieve social impact.

If you have any questions or information you’d like to share, you can get in touch at lino@onfife.com

Linoleum Lives!

Linoleum is not only an amazing floor covering, but also lends itself to producing intricate artworks.

The artwork below shows the Queen Elizabeth, a cruise liner which shuttled between Southampton and New York for over 20 years. The ship was built to replace the Aquitania, which had been in service since the 1910s. Along with its sister ships the Mauretania and the Lusitania, it was built by the Cunard line to compete with the White Star lines Olympic-class liners – the Britannic, the Olympic and the Titanic.

Despite being just a few degrees of separation from the fame and tragedy synonymous with these vessels, the Queen Elizabeth enjoyed a life which was long but largely uneventful. This is a nice picture of a big ship, but that’s not what makes it special. What really makes this object incredible is that it’s made entirely of linoleum.

Linoleum picture of RMS Queen Elizabeth. Donated by the late Dr RGW Prescott FSA (Scot.). FIFER:2022.147.

Each section of the picture is a precisely cut piece of linoleum, arranged to give the impression of the steamer at sea. We don’t know who made this picture, or when. It seems likely that this would have been around the time the ship was launched in 1939; it then spent several decades hanging in the Britannia Hotel on South Street, St Andrews. A label on the back of the picture indicates that it was framed by Haxton of Kirkcaldy, which suggests it may have been created in a Kirkcaldy linoleum factory, or by someone who lived in the town.

So, why would you make a mosaic out of linoleum? Though it seems a strange choice at first, there are lots of good, practical reasons which make lino an attractive art medium. It’s easier to cut to shape than wood or tile – over which it also has a price advantage. Plus, any designs made this way will be as easy to clean and care for as a kitchen floor – whereas a paper collage or painted picture might well look as though they’d be through the wars after a few decades on display. This durability is the same reason that linoleum was often used to floor large ocean liners, including the ill-fated Titanic and Lusitania, and probably also the Queen Elizabeth itself.

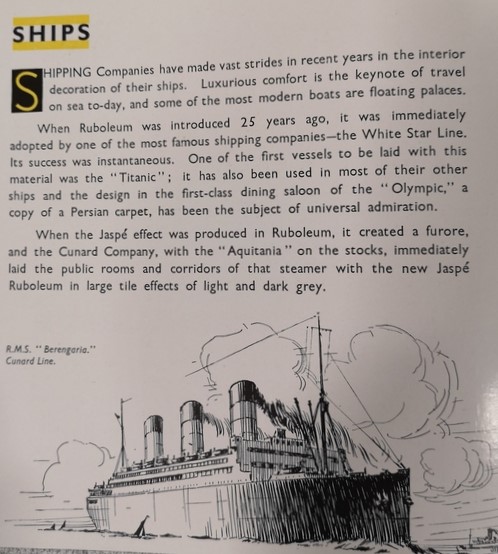

A page from Barry and Staines Ruboleum and Linoleum catalogue. KIRMG:1982.393.

The practice of making designs out of different shapes and colours of linoleum is also not restricted to artistic endeavours. From its invention in the mid-19th century, decorative linoleum was created by printing designs on the surface of the material. This was a time-consuming process, as each colour had to be applied using a different printing block, the edges of which had to be closely matched to create the overall effect. There are some printing blocks in our collections, which are around 45cm squared in size – the process of layering each colour would have to be repeated to cover the entire surface of the length of linoleum.

Though this allowed companies to create intricate designs – such as this nursery rhyme themed pattern – it had one serious weakness. Over time, the designs would wear away, limited the lifecycle of the product at a time when durability was highly-prized by potential customers.

Nursery linoleum in Designs in Floorcloth catalogue of the Kirkcaldy Linoleum Company Ltd. FIFER:2022.150.

In response to this, Frederick Walton – the man who had invented linoleum in the 1860s – developed inlaid linoleum, whereby designs were built up by piecing together different coloured piece of lino. Walton later developed a mechanical means of creating inlaid linoleum, making a product which was quicker to create as well as more durable than printed lino.

Example of inlaid linoleum. FIFER:2017.18.

In Kirkcaldy, however, this process continued to be done by hand, as well as by machine. It was usually done by women factory workers – who were encouraged not to talk so that they could concentrate on the intricate and time-consuming process.

Making inlaid linoleum. TEMP:2012.4426.

You can find inlaid linoleum designs in many public buildings. In Kirkcaldy, an inlaid linoleum design welcomes visitors to the railway station, and there is also a linoleum map of the Lang Toun in the Town House.

The Queen Elizabeth joins four other lino artworks at our collections centre in Glenrothes: two landscapes, one showing Lambeth Bridge, London, and the other showing an unidentified country scene (somewhere near Oxford and Bath, if the sign-post is to be believed); and two portraits, of Queen Elizabeth II and the Duke of Edinburgh. Framed linoleum mosaics are extremely rare – we are not currently aware of any other objects like this in museum collections – this is something I’ll be researching as the project continues!

Hand-cut portrait of HM Queen Elizabeth II made of Kirkcaldy linoleum in 1955. TEMP:2016.64.

_________

This blog was written by Lily Barnes, curator working on the linoleum project Flooring the World (2022-2024). Flooring the World is a two-year project exploring the history of the Fife linoleum industry. It is funded by the Esmée Fairbairn Collections Fund, which is run by the Museums Association, funding projects that develop collections to achieve social impact.

If you have any questions or information you’d like to share, you can get in touch at lino@onfife.com

![]()

Uncovered: bringing Fife’s collections back to life

In 2017 OnFife Collections staff, and a fab team of removal professionals, transported more than 82,000 objects (including 1,000 works of art) from a variety of locations across Fife to a new museum and archives store within our Collections Centre at Bankhead Central in Glenrothes. This move meant that most objects would be kept in one building, secure and free from damage in stable, environmentally controlled conditions.

Since the move our Museums Collections team have been working hard to update the locations of these objects. This is important work as we need to know exactly where our objects are in the stores so they can be used in new exhibitions and made available to researchers.

Some objects, those too big or unusually shaped to fit into boxes, were wrapped for the move but others had been wrapped for years, to protect them from the less than ideal stores we had previously. In July 2021, I started working in the stores to unwrap and photograph these ‘Unboxed’ collections and to update their locations on our Collections Management System (Museums database). I also check and record the condition of the objects, clearly label each one with its accession number (unique numbers we use to identify each object) and improve the description and/or details of the objects on our catalogue.

Before and after: Black metal Triang doll’s pram, from around 1950s. DUFDM:1990.0063

OnFife colleagues within Local Studies at Dunfermline Carnegie Library and Galleries have helped us discover new information on some of our objects. This trunk was used during the second World War by Captain D Drysdale, but we had little recorded information on him.

Metal trunk of Capt. D. Drysdale. DUFDM:1993.0198

We now know much more about David Drysdale, his military service, details of his career in banking, his involvement in many local organisations, service as Honorary Sherriff Substitute for Fife and as a Justice of Peace. These important details are now recorded on our catalogue.

Challenges including the pandemic and issues with technology have caused some delays in the project, but big strides have still been made. Over 500 objects have now been Uncovered, their locations updated, and information on the object records enhanced.

Painted clock faces in wrapping.

Swathes of tissue paper and bubble wrap have been removed and improvements within the Collections Centre store can be seen every day.

Before and after: rows of objects, previously wrapped in tissue and bubble wrap, are now accessible to staff and visitors.

Thanks to Museums Galleries Scotland’s Small Grant Fund for funding which has allowed us to purchase new equipment and to trial the use of new technology as part of the Uncovered Project.

_____________

This blog was written by Susan Goodfellow, Collections Support Assistant, Uncovered project.