JANE CALVERT DUNCANSON, 1854-1945 – A DUNFERMLINE BLUESTOCKING.

(With a note on the degree of LLA).

The term bluestocking was first used in the 18th century for ladies who gathered in groups for intellectual conversation and was extended to educated women generally, sometimes in a derogatory fashion. It probably stemmed from the blue hose worn by working people which was regarded as eccentric when worn in polite society. Jane Duncanson, who was early in the field of advanced education for women in Scotland, may well have been regarded as a bluestocking by her contemporaries in Victorian Britain.

Jane Calvert Duncanson was born in the Parish of Inverkeithing on May 13th 1854, the first of the seven children of Thomas Duncanson, a mason and master builder, and his wife Elizabeth Milburn from Cumberland. The Duncansons lived successively in New Row, Campbell Street and 10 Appin Crescent, Dunfermline.

Jane seems to have been a clever and ambitious girl set on a career in teaching, with a leaning towards science. Educated locally, by the age of 16 in 1871 she was employed as a pupil teacher and was taking French lessons in Edinburgh. In 1873 she began a teaching course at the Edinburgh Free Church Training College, doing her probationary training at St. Leonard`s Works School in Dunfermline. From 1874 until 1889 she sat numerous examinations under the auspices of the Privy Council Committee on Education in London, the Normal School of Science in South Kensington and other bodies. Among the subjects she studied were education, French, mathematics, botany, animal physiology, inorganic chemistry, sound light and heat, physical geography, political economy and hygiene for which she was awarded a medal.

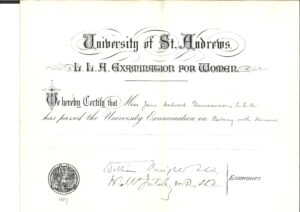

In 1875 she obtained her Teachers Certificate Second Class, which in 1888, after years of service, was duly raised to First Class. In 1877 Jane`s success in French, English, Education and Political Economy gained her the qualification of LA (Literate in Arts) which had been established for women by St. Andrews University as the nearest thing to a degree. Jane was one of the first eight women to obtain this qualification. As there was already a LA qualification for men in Edinburgh, St. Andrews changed LA to LLA (Ladies Literate in Arts) which Jane obtained in 1884 with Education (Honours), Political Economy and French (Honours). In 1887 she added Botany with honours to her LLA qualification.

In 1881 aged 26 Jane was still living at home in Appin Crescent and working as a teacher. Her father Thomas Duncanson aged 51 was described as a master mason and quarrymaster, employing 33 men. Thomas died in January 1883, aged 53 having been 25 years in business in Dunfermline; his wife Elizabeth Milburn died in 1910, having moved next door to 8 Appin Crescent.

On September 10th 1887 the Dunfermline Press announced that at the `Dunfermline School of Science and Art – Miss J. C. Duncanson, LLA, will begin a class in Elementary Botany in the New High School Tuesday 20th September 6.30-7.45: fee for the course 10s`.

Apart from being a pioneer in women`s education, Jane adopted other modern ideas. She was a member of the Rational Dress Society (probably a protest against corsets and other restrictions) and in an advertisement for `reform cotton wool` in the Kilkenny Advertiser for June 1889 Miss J. Calvert Duncanson of Cardiff was said to have found the new fabric comfortable, elastic and easily washed

When she was about 36 Jane had moved to Cardiff and set up home with her younger brother John, an elementary school teacher. During her training Jane had studied French at a pensionnat in Paris and in 1890 she returned to visit Parisian schools to study their methods. At this time Jane was appointed headmistress of Cardiff Higher Grade School which was founded in 1885 to prepare children for entry to the University College Cardiff founded two years earlier She succeeded Miss Ramsay, probably another Scottish lady, who also had the qualification of LLA.

Jane was not long in her new post as in1891she married a Cardiff shipowner John Gower Marychurch who was one of Cardiff`s leading citizens and a foremost shipper of coal from Cardiff Docks. The 1901 census finds the couple living in Park Place Cardiff with Jane`s lady`s help, Lucy Grant, a cook and a parlourmaid. In December1909 John Marychurch died aged 70, bequeathing large sums to charity and leaving Jane a wealthy widow of 44.

Jane, seated centre, with her servants outside her Cardiff house

Jane was a woman of spirit. In March 1911, newly-widowed, she went as a tourist to Springfield, Ohio, travelling on the Cavonia to New York. She was described as aged 56, 5`4” tall with grey hair and eyes and a fair complexion. Her relative in the `old country` was given as her brother J. Duncanson of 8 Appin Crescent Dunfermline.

Jane then moved to Weston-super-Mare, Somerset, and in 1939 aged 85 was living there with her companion Lucy Grant and a maidservant. Jane died at Weston-super-Mare in November 1945 leaving the considerable sum of £6441:11s:10d. Cremation was not yet common but Jane was cremated `by her own wish` in Bristol. Jane Calvert Duncanson or Marychurch was a modern woman to the end.

THE DEGREE OF LLA (Ladies Literate in Arts)

In the 1870s there was growing demand from women keen to obtain an education and to improve their chances in life and evening classes in selected subjects began in Edinburgh. It is likely that Jane Duncanson attended some of these while she was a student from 1873-5 at her Edinburgh training college.

Enlightened men and women in St. Andrews took up the challenge and in 1877 introduced the Higher Certificate for Women, with a choice of 20 literary and scientific subjects, `to stimulate women in the pursuit of higher learning`. It would be of `great advantage to teachers and especially advantageous for those who can`t attend university but who aimed at advancement by private study` (Fife Herald, Dec. 28 1876). To obtain the diploma of LA (Literate in Arts) candidates had to pass four subjects, including a language and, as we have seen, Jane Duncanson was among the first eight women to qualify, passing examinations in French, Education, English and Political Economy.

From 1881 candidates had to have a Local Education Certificate; in 1883 the number of subjects was raised to five and in 1887 to seven. By 1886 there were 24 subjects on offer and the LA had become the LLA (Ladies Literate in Arts) to differentiate it from a degree of LA offered for men in Edinburgh. The LLA increased in popularity, especially after a lecture tour in 1887, and it existed until 1931 (Details obtained from a University of St. Andrews Special Collections Blog `Examinations for Ladies Literate in Arts, May 8 2019).

Memories of the time we were evacuated from Edinburgh to Cupar.

By Doreen Carmichael (nee Clapperton) dob 18/06/1928

I was eleven in the summer of 1939 when I heard talk of war. I knew about the first war of course, songs like Tipperary and Keep the Home Fires Burning were still played a lot on the radio alongside Lambeth Walk and Underneath the Chestnut Tree. This was way before Vera Lynn and the White cliffs of Dover. I knew about war from listening to adults or maybe from the Pathe News when I went to the cinema. I heard about soldiers coming home from Palestine and from the civil war in Spain. I’d read about Florence Nightingale and the Crimean war from a schoolbook. I didn’t know where any of these places were. I remember that air raid shelters were being built, one in the meadows and some people were having one in their own gardens. I thought that our family were safe because my Daddy was not going to be a soldier – he was away in the Royal Navy. Well, as I’ve said, I was only eleven. I don’t remember much about getting ready for evacuation day on September 1 st and I find that strange because our usual routine must have changed. I wonder how my mum managed, she was 34, she wouldn’t have wanted to leave her home. Her husband was miles away and she had to decide whether to evacuate or not. The powers that be were telling her that her children should be sent to the country for safety. She would also be worried about her mum who was on her own and a bit needy. Once the decision was made, clothes had to be packed and older children had to have their own bundle. We gathered at Sciences School in Edinburgh. A long line of mums, school children, toddlers, babies and teachers with bags, suitcases and gas masks. We walked to Newington Station and waited for the train. It was a “no corridor” train which meant we were locked in.

Our carriage was packed, my mum and her seven children, another mum with a young baby and a music teacher. We weren’t told where we were going and the train stopped often, not at official stations and we didn’t know why. The carriage got smelly and the baby’s nappy was changed. The train reached Cupar although I don’t remember arriving. My next clear memory is living with Mr and Mrs Lawson in a house at the top of Bishopgate and my young sister Joyce is with me. Mum and my other siblings were housed further down the road. I don’t remember which day we arrived in Cupar, but I do know that come the first Sunday morning we were told that war had been declared so that was the 3rd of September 1939. It was a nice sunny day and it seemed all the adults were out on the streets chatting to one another. The Lawsons were kind to us and I remember they had a young man staying with them. Joyce and I got out to play and we met other children. The name Louise Plunket comes to mind, I think she was a local girl and lived in a big house further down the road. We attended Castlehill Primary School. I would be in P7, I don’t remember much about that time and it was only much later that I realised how very important the P7 year is in a child’s development. I don’t remember how or why everything changed but it did. Mum and my younger siblings were now living with Mr and Mrs D J Bruce, at Mount Pleasant. I often wonder what Mum thought; it was a big house with oil lamps and an outside toilet. There was no hot water, the only tap was in the “lean to” kitchen. Joyce and I were still in Bishopgate and often walked up the South Road to see Mum. On one of these visits Mum noticed my head had nits and she wouldn’t let Joyce and I go back to Mrs Lawson’s which is why Mrs Bruce got landed with the whole Clapperton family. I later heard that Mr and Mrs Lawson didn’t want us back because she was pregnant. I hope all went well with that because they were nice people. So, there we were at Mount Pleasant with Mr and Mrs Bruce, mum and I, Lena, Joyce, Audrey and baby Percy. I remember Mr Bruce as being well into his eighties and in poor health. My brother Richard was billeted with a lady down the road, I only saw him if he was playing in the little front garden. Joyce and I were sure the lady in that house was a spy because she wore trousers. My other brother Jack was living at Tarvit Hill Mains Farm, along the road from Mount Pleasant and up a hill. I remember seeing him when he was coming back from school. Often over the years, I’ve felt great sadness at the thought of him making that journey and I don’t know why he and Richard were eventually sent to live somewhere in Springfield. So much was happening in our lives and I never knew why. Back to life in Mount Pleasant and whilst I can’t remember the right order of events I recall; mum went back to Edinburgh with baby Percy, Mr Bruce died and the Thompsons, Dorothy, Robert and Helen came to live with us. The Thompsons came from West Newington Place, Edinburgh. Later in life when living near there I met many people who remembered them. Mr David James Bruce was quite tall and a little stooped, in his eighties and not in the best of health. I’ve often wondered what he thought about all of us being billeted in his house. I wonder, did he and Mrs Bruce have any say in the matter? He died soon after we arrived. I understand that Mount Pleasant had been his family home and was told that when his father was dying the road in front of the house was covered with straw so that it was quiet for him. Mrs Bruce must have been in the house because, as she told me, she nursed Mr Bruce’s mother. The details of that were pretty awful, it was the first time that I had heard the word cancer. I don’t know what Mr Bruce did in his working life and I wonder if he always spent a lot of his time gardening. The garden was well laid out with fruit trees, apples, plums, and pears. Soft fruits such as black and redcurrants and strawberry beds, also artichokes (I’d never heard of them).

There was always lots of lettuce and vegetables. I remember learning how to store apples, each apple was half wrapped in newspaper and laid with a little space between them on a shelf and in a dark place. Mrs Sarah Henrietta Bruce was the daughter of Walkers the bakers in Dundee and she spoke of a sister who live in Ballater. Mrs Bruce was a little old lady, under 5 feet and very bow legged, her hair was snowy white and as far as I can remember it was always neat. There were some out houses at the back of the main house and one was used to store food for the hens. The hen house was at the top of the back field that sloped down to the river Eden. I remember mixing food for the hens and spreading it over the grass, soon the hens would be pecking all round me. Another memory is being sent to the hen house to bring in eggs. They were usually big and warm. Some of these eggs were sold, some were pickled in waterglass and, of course, with 6 children and one adult many eggs were eaten. (In general eggs were rationed to one a week or one a fortnight.) Did we ever eat one of our hens? I don’t know, but I do remember being told that a particular bird was past laying. I don’t remember much about what we got to eat but a very clear memory is that the dining table had to be properly set, one of us would be sent to pick flowers for the table and just like at home in Edinburgh, we had to ask permission to leave the table. As I’ve already said the kitchen was a ‘lean to’ at the back of the house. It had an ancient gas cooker, a stone sink and one cold water tap. Wet dishes were placed in a wooden rack above the sink. I can’t remember what was used to clean dishes; it certainly wasn’t fairy liquid. The floor was stone, uneven and always cold. The place had a smell that I came to know was mice, but I don’t recall ever seeing one of the little creatures. All of us washed at that sink and that is probably why I remember it always being so cold. What I don’t know is where the gas came from, I never saw a bottle in the kitchen and for a long time we were using oil lamps. As for the wireless, I’m guessing it must have been on an accumulator. At home in Edinburgh, we used accumulators before we got electricity. We must have settled ok as I don’t remember any major upsets. Time passed and I went to Bell Baxter High School. Dorothy Thomson will have done also but I don’t remember. On Sundays, some of us went to church (St James Episcopal) three times as I remember; Early morning service, Sunday school and the evening service. Mrs Bruce had some of us confirmed in the church. Joyce and I wore our Guide uniforms and some of the other youngsters wore the more usual lovely white outfits. Sunday evenings, we listened to the news on the wireless. We heard how many German planes had been shot and how many of ours were lost. I’m sure that there must have been more news, but the plane count was what we waited for. The programme ended with playing the anthems of different countries Mrs Bruce and all of us children stood to attention for that. I’m sure I didn’t dwell on “we are at war” but some events would remind me. When the siren sounded Mrs Bruce would get us all downstairs, then we would put our gasmasks on and sit with her on her bed until the all-clear sounded. The masks were so uncomfortable, it must have been so awful for the wee ones. A nicer memory is going out for a walk in the dark and watching the searchlights playing across the sky, beautiful really. I’m not sure how this came about, it might have been arranged by the church. A group of us children were introduced to some Polish soldiers. I do remember chatting to a young soldier who told me he’d had to leave his home just as I had. He gave me a book about Warsaw and an eagle badge, I would have been about 12. I don’t know what happened to those lovely gifts. Thinking about South Road again, across the road from us the Robertson sisters lived. I don’t remember meeting them, but I was told that their afternoon tea was bread and butter with jam, or bread and butter with cake. Jam or cake. The Gordon sisters lived just up from the Robertsons. My young sister Joyce was often in their company. Joyce was friends with another family and I think their name was Nash. The Nash house was a bit up the road from us, it was a big house and close to the river Eden. I’m not sure if the family Nash were American or had just come from America. Still on the South Road, up a hill was Tarvit Hill Farm (my brothers were billeted there for a short time) and not far away is Tarvit Hill House. I think it may be a hospice now. During the war it was the home of our Guide Captain, Miss Elizabeth Sharp. I read some years later that she became head guide for Scotland. She died quite young. Our Guide group met in Tarvit House and that was just up from the railway station. The grounds there were absolutely beautiful, a big garden with very many old trees. The garden needed weeding and some of us guides tried to help with that. Some memories are so very clear. During my time at Bell Baxter, I was chosen to present flowers to a visiting dignitary. I don’t know what the occasion was, but the sweet peas I carried were beautiful. I also remember our one and only visit to a cinema whilst in Cupar, Dorothy Thomson and I saw a Gracie Fields film. I don’t know what the film was, but I knew that Gracie was no longer popular because she married Monty and went to America. (I must have heard adults discussing this before the war).

Over the years I kept in touch with Mrs Bruce and in 1950 invited her to my wedding. She was unable to come but sent a lovely present to me at my place of work, Elliot’s Bookshop in Princes Street. I hope that I wrote to thank her, my mum was very ill in hospital at the time and some things just didn’t get done as they should. I went to Cupar in 1951 and found that Mrs Bruce was well and looked just as she had done in the early forties. We walked in the garden for a while and had our pictures taken. I went back in the summer of 1953 and found Mrs Bruce was in bed, she didn’t say what was wrong however she seemed content with her wireless and a paper. There were other people living in the house and I suppose that they were looking after her. Later in 1953 my husband and I went to live in Nigeria. I wrote to Mrs Bruce but didn’t hear back. During the 80’s my sister Joyce and I visited Cupar on a number of occasions. We would walk from the railway station up South Road, peek over the wall to see “our” garden and remember our times there. We couldn’t understand what had become of Tarvit House although I now believe that it was demolished and the land used for new housing. I do hope the builders managed to keep some of the lovely trees in place.

And so to the present time, 2022. In August my son, his partner and I took a trip to Falkland Palace and after we went on to Cupar. We went up the South Road, but it was pouring with rain and so didn’t get out for a walk. From the car we could see the fruit trees, laden with apples and plums. Would they be the trees that were there in the thirties? I don’t know. Once back home, I was thinking about Mount Pleasant and wondered if the present owners knew of its evacuee history, so I set myself the goal of finding out. It turns out that the lady who now lives in that house had heard about evacuees and had been looking for information. She wrote me a lovely letter and I hope I will be meeting her at some time. Having shared my exploits with my good friend Sheila (a wizard on the computer), she kindly trawled the archives and found the obituaries for both Mr David Bruce in The Courier and Advertiser (02/02/1940) and Mrs Sarah Bruce in The Fife Herald and Journal (07/09/1955). I see now from Mrs Bruce’s obituary that sadly she was most probably in Methilhaven Care Home when I wrote to her from Nigeria in 1953 hence, I didn’t hear back. I wonder how it is that not a hint of Mr and Mrs Bruce’s fascinating history was known to any of us children when we lived with them?

Doreen Carmichael, August 2022

ON at Fife Archives

Index to CASTLEHILL School Evacuees admission register

This index was created for OnFife Archives by David Ritchie, volunteer. This is a name index to a register of evacuees who attended Castlehill School in Cupar.

Castlehill School kept a separate register for evacuee children who were admitted to the school between 1939 and 1945.

I/A/3/206 Clapperton, Audrey – Evacuee 13/09/1939

dob – 21/09/1932 Parent/Guardian – Clapperton, Percy Cupar Address – Mt Pleasant, South Road Previous School – Sciennes Date of Leaving – 30/03/1942 Destination – Rothesay

I/A/3/53 Clapperton, Doreen – Evacuee 13/09/1939

dob – 18/06/1928 Parent/Guardian – Clapperton, Percy Cupar Address – c/o Lawson, 44 Bishopgate Previous School – Sciennes Date of Leaving – 12/07/1940 Destination – Bell Baxter

I/A/3/106 Clapperton, John – Evacuee 13/09/1939

dob – 30/09/1939 Parent/Guardian – Clapperton, Percy Cupar Address – c/o Taylor, Tarvithill Farm Previous School – Sciennes Date of Leaving – 03/01/1940 Destination – Springfield

I/A/3/146 Clapperton, Joyce – Evacuee 13/09/1939

dob – 19/03/1931 Parent/Guardian – Clapperton, Percy Cupar Address – South road Previous School – Sciennes Date of Leaving – 30/03/1942 Destination – Rothesay

I/A/3/321 Clapperton, Richard – Evacuee 06/11/1939

dob – Parent/Guardian – Clapperton, Percy Cupar Address – [not given] Previous School – ‘Ent. Infants’ (entry date indicated as ‘re-admission’) Date of Leaving – 18/12/1939 Destination – Springfield

`HORSES` BY MIMA ROBERTSON, born 1901

Looking back on my childhood it seems that horses and ponies played an important part in it. John Goodall had a large livery-stable, which provided cabs for the station – luggage on the roof – carriages or landaus for special, with sometimes two horses, gigs and pony-carts, hearses with handsome black horses decked out with black plumes. Father used to hire a Shetland pony for me to ride when I was about five but that did not last long as Mother was afraid I would fall off and injure myself. (Later I got a bicycle on which I performed far more hazardous feats – tramlines made cycling dangerous as it was easy to catch ones front-wheel in one when speeding down the steep Townhill Road).

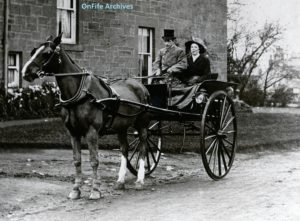

But my great delight was when Father summoned a `trap` from Goodall`s, perhaps in a late summer afternoon when he had returned from the office. This was a lightweight vehicle with two high wheels and a seat for two perched up behind the dashboard and usually a mettlesome animal between the shafts. With a rug round my black-stockinged legs and my feet not touching the floor I would sit by Father`s side while he, expertly handling the reins and the slender whip, would take us out into the country, down to Limekilns perhaps and round by Saline. Then, as there was very little traffic on the roads, I was allowed to experience the thrill of driving the horses myself, learning to hold the reins properly as we went along at a smart pace that only slackened when climbing a hill. That was a real treat and I`m sure Father enjoyed it as much as I did.

Then there were the tradesmen`s horses, tramping down the avenue to the yard where they took sugar from me while the baker – Allans, with a very smart van high-sided with gold lettering on red paint – or the butcher or the grocer had a chat with the housemaid at the back door. Our Doctor Fleming who had a small brougham in winter, an open Victoria in summer, also made frequent calls. His coachman, Peter McArthur, was a firm friend of mine and he sometimes took me off for a turn round the Park while the doctor was taking Mother`s pulse. He was never in a hurry and never complained when we kept him waiting. Changed days indeed!

Dunfermline Cleaning gang with horses

Ashes and house-refuse were collected by another horse-drawn vehicle belonging to the town corporation from the stone-built rubbish-container at the top of the garden between the greenhouse and the wash-house. I met other horses on my way through the town and often stopped for a chat as they stood patiently by the pavement. There were always two or three horse-drawn cabs waiting at the Lower Station – in those days Dunfermline was an important railway-junction and one could take trains to Edinburgh, Perth, Stirling, Alloa, St. Andrews, etc. at frequent intervals. The bus that went to Limekilns and Charlestown was horse-drawn and for some years after the `14 War could be found waiting at the Glen gates near the Abbey.

When I was about eleven Mother and I stayed one summer holiday at the Athol Palace, Pitlochry, and went on a wagonette to Braemar. There were four horses, passengers inside and out, and when we reached the Devil`s Elbow everyone except the driver had to walk up – and later down – the steep curves of the road. I was on the box beside the driver – trust me! – and was allowed the honour of holding the reins for a short spell. Driving four horses, spanking along – I have never forgotten it.

Thanks to Cupar Local Studies for the majority of the photographs.

NOTE ON MIMA ROBERTSON

Mima Robertson was born in 1901 to John Whyte Robertson and his wife Jemima Taylor and was baptised Jemima Simpson Taylor Robertson. Her father worked for the family firm of Hay and Robertson, linen and cotton manufacturers, and her mother was the daughter of John Taylor a West Indian merchant. The couple already had two children, Margaretta born in 1889 and William born in 1893. In 1891 the family lived

at Dunsloy Villas, New Row, in 1901 at 3 Comely Park Place, and from about 1906 at Witchbrae, Townill Road. Witchbrae had been built in about 1860 for the Hay family and was advertised for sale in 1926 as a `fine dwelling house` set in two acres of grounds with excellent views to the south. It was lit by electricity, had several public rooms, six bedrooms, bathrooms, two bedrooms and a bathroom for the maids and numerous utility rooms and outbuildings. The Robertsons kept at least three female servants as well as the outdoor staff.

After an early education at Roseberry House, a private school in the Masonic Lodge, New Row, Miss Robertson was sent to boarding-school. She was so unhappy there that she was brought home to be educated by a governess. The governess, apparently an inspiring teacher, had taught classics at a boys` school and now she taught Latin to Mima, who found it stood her in good stead in her writing.

Mima had written stories from early childhood and when she was 19 received her first payment, 20 shillings from Punch for a humorous article. She loved to travel especially to Brittany and in 1926 she had a story called A Change of Air, set between Brittany and Dunfermline, accepted by a London agent and publishers, who changed the title to The Leopard`s Skin. Other novels with a Dunfermline connection were The Sport of Circumstance and Bitter Bread , while After Stormy Seas was again based in Brittany and Music in the Air in Gottland, the Baltic island, also a holiday destination.

Then followed two historical novels under the name `Alison Taylor`, Alison because it was Scottish and Mima liked it better than her own, and Taylor, her mother`s maiden name. For a change, Evil Enchantment of 1930 was a psychological thriller which she felt would have made a good film.

In the early 1930s when her writing had become a real necessity Miss Robertson was invited to contribute serials to the magazines run by Leng Publications of Dundee, particularly the People`s Friend. She was associated with the People`s Friend for some 40 years and found that writing to order involved a strict routine unlike the free-and-easy hours she had been used to. She continued to write novels and in 1953 published The Castilian, a historical novel about William Kirkcaldy of Grange, who was executed for his attempt to hold the besieged Edinburgh Castle for Mary Queen of Scots.

Mima Robertson had talents other than writing. She played first violin in Dunfermline Amateur Orchestra and was an artist and a needlewoman. She captained the Dunfermline Tennis Club ladies and became President of the Dunfermline Soroptimists. Miss Robertson never married and during the depression of the 1930s, when the family fortunes plummeted, the income from her writing became even more important. From Witchbrae, Mima and her parents moved to 9 Cameron Street where her mother died in 1944 and her father in 1959. Miss Robertson then moved to a flat at 15 Cameron Street and it was here in 1979 that she wrote her magnum opus Old Dunfermline and where she died in 1985 aged 83.

In Miss Robertson`s article on horses, the house referred to is Witchbrae and one of the six bedrooms probably became the schoolroom and what Miss Robertson called `My Room`. `Neil` was the gardener Neil McLean, and `Miss Nimmo` possibly the `nurse and sewing maid for one girl 4½ years` that Mrs. Robertson advertised for in 1906. Or perhaps `Miss Nimmo` was the governess who did sewing as well. The sources for this biography come from various on-line genealogy and newspaper sites, from Dunfermline Press, March 13 1970 (largely reproduced in Hugh Walker`s The History of Hay and Robertson, 1995) and Miss Robertson`s papers, which include (possibly unpublished) stories and plays, and are currently being archived at Dunfermline Carnegie Library but are not yet catalogued.

This is the second blog from our fantastic volunteer Suzie, in celebration of International Women’s Day

Anna Munro

Anna Gilles Macdonald Munro was born in Glasgow in 1881 and died in 1962 . Her father was a school master and the family lived in Edinburgh until 1892 when Anna’s mother died and then she and her sister, Eva, moved to Dunfermline to live with her paternal Aunt and her husband, Pastor Jacob Primmer.

Having worked for three years for The Sisterhood of the Poor Movement in the East End of London, Glasgow and Edinburgh, Anna was very moved by what she saw. A lifelong supporter of the Labour Party, she served as both chair and president of her local committee. Her fight for female franchise was compassionately rooted in helping women in poverty.

Anna joined the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) in 1906 and became its organiser in Dunfermline. However the WSPU was becoming less democratic and there were concerns that its leadership under Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst was becoming dictatorial. Anna and several members, including Charlotte Despard and Teresa Billington-Greig broke away and created the Woman’s Freedom League (WFL).

Teresa Billington-Greig was the first Suffragette sent to Holloway. Charlotte Despard was the first woman to refuse to pay taxes as a protest, an action which quickly inspired others to form the Women’s Tax Resistance League (these activities were expanded upon in Apr 1911 when the WFL passed a resolution to boycott the national census protesting against the omission of women’s suffrage for the Kings Speech sending copies of the resolution to Asquith and Churchill. Women householders either spoilt or failed to complete their census forms) In 1907 Anna became Teresa Billington Greig’s personal secretary.

The Women’s Freedom League grew rapidly, and soon had sixty branches throughout Britain with an overall membership of around 4,000 people. This was over twice the size of the WSPU. The WFL also established its own newspaper, “The Vote”

The WFL classed themselves as a militant organisation (over 100 of their members were sent to prison after being arrested on demonstrations or refusing to pay taxes), but unlike the WSPU they refused to attack people or property other than ballot papers. Their actions included protests in and around the House of Commons and other acts of passive civil disobedience such as payment of taxes; their principal being ‘no tax without representation’. WFL activities in 1908 included attempts to present petitions to the king and have deputations received by cabinet ministers while further protests were held in the House of Commons such as Suffragettes chaining themselves to the grille in the Ladies gallery.

In January 1908 Anna took part in a deputation to see Cabinet Minister Richard Haldane. The WFL had petitions protesting against the omission of Women’s Suffrage from the King’s Speech and asked him to use his vote to get the measure passed. When Haldane refused to come out to meet them Anna pinned a large “Votes for Women” flag on the door and told the crowd “OK we will wait for him” and addressed the crowd. The police attempted to move her on and suggested she “go and buy some chocolates” and Anna accused them of impudence, carried on addressing the crowd and was arrested. At her trial she stated “I have come from Scotland for this purpose. I lost my hat yesterday in the crowd, trying to present petition to the King.” On reporting the trial the Dundee Courier claimed her to be “an excellent and fluent speaker”. She was imprisoned in Holloway Prison for six weeks.

A letter in the Aberdeen Press & Journal 5th February 1908 from Pastor Jacob Primmer, Anna’s uncle, to the Home Secretary (Herbert Gladstone) :-

“The Manse, Kingseathill, Dunfermline, 31 Jan 1908

Dear Sir

As the uncle of Miss Anna Munro who at Westminster Court yesterday , got the cruel and vindictive punishment of six weeks imprisonment – while for the same political offence the sentence at Marylebone was 40 shilling or twenty-one days imprisonment and 40 shilling, or one month, as a Suffragist – allow me to point out that for long she has been in delicate and precarious health; that only four weeks ago she fell down in a faint in a Glasgow street; that imprisonment will be most serious in its consequence; that therefore you should order her liberation from prison, and that until that be done she should be kept in the infirmary.

On 8th February E Blackwell responded on behalf of the Secretary of State saying he could find no grounds for releasing her. However her uncle had already received a telegram (S7) saying that she was free after someone had paid surety of £20 (Dundee Courier 12th Feb 1908).

Jacob Primmer responded that his niece had been arrested for

“the awful crime of knocking up some of your fellow Cabinet Ministers at 9:30am and holding outside public meetings until they made their appearance. It was my niece who put the question to the Prime Minister in Dunfermline on 22nd October last –

‘As the Prime Minister believes in Women’s suffrage would he suggest some method we could adopt in order to get our enfranchisement soon? He said I think they ought to go on agitating and holding meetings and pestering people as much as they can, as all other men and women who are interested in public questions have to do.’

Is not, therefore, outrageous and the playing of the tyrant keep them in the common prison among the vilest the nation for following the advice of your superior—the head the Government? Remember that cruelty and intolerance never pay, even the part of a Home Secretary. Is it not farcical to charge a frail and weak young lady with resisting number of elephantine, six feet five inches policemen? And for this awful crime to suffer six weeks Holloway Prison? Doctors and others Dunfermline can bear testimony to the delicate and precarious health of my niece, yet you say that she ‘is fair general health’. This is emphatically contradicted in letter received from her this evening. She writes—‘you know, I came out of Holloway last night after being in ten days. It was either case of that or hospital!’ And she complains suffering from a frightful headache. It would be well if in future you got some honest, reliable person to give you information to the condition those tyrannically cast into prison. I write in the interests of fair play and protect, against your turning the administration of the law into farce.”

On returning to Dunfermline a suffragette meeting was held to welcome Anna back. The principal speakers were “Anna Munro, Dunfermline and Mrs Sanderson, Forfar” both who had suffered imprisonment in Holloway. Anna stated that since her last appearance she had “lost her character and had become a gaolbird”. Describing her arrest, she said they were not guilty of the dreadful things that were read of in the papers. They did not shout, they did not scream; it was an exceedingly dignified matter altogether. At Mr Haldane’s house they pinned a “Votes for Women” flag on the door. Six policemen came along, and they went with them very properly, and did not resist in any way. There was not a single woman allowed into the Court. They asked if she wished to say anything her own defence but when she- had opportunity to say anything was simply shouted down. She did not hear the sentence; she heard murmur from the bench, and then she was removed.

Anna was good at addressing meetings; she was eloquent and charismatic and spoke without notes at many meetings and in December 1908 Anna became the WFL organising secretary in Glasgow. The Scottish Council of the Women’s Freedom League was based at 30 Gordon Street, and also ran a tearoom and bookshop at the Suffrage Centre, originally in Sauchiehall Street and later in St George’s Road.

In 1910 there is a picture/photo of her in prison “garb” saying that she will take active part in the campaign against Mr Churchill during the election. Churchill was first elected MP for Dundee in 1908 after failing to keep his Manchester seat. His re-election in Dundee was fought by the WFL who organised many meetings in December. Churchill did not back women’s suffrage. When asked why he wouldn’t give women the vote or political rights he responded “you have political rights as exercised through your husband.” In December 1910 Churchill visited Dundee. On the 6th December 1910, at the Corn Exchange in Albert Square Dundee, Charlotte Despard and Anna spoke out against Churchill for acting against Liberal principles. Anna is quoted as saying that when Churchill came to Dundee he said ‘Trust me Ladies I am your friend’ but “the ladies did not trust him and his subsequent action proved them correct”.

Also that week in Dundee she spoke at ten different protest meetings at King’s Theatre, Caird Fountain, Baxter’s Works, the YMCA , the High School Gate, Cox’s works, at the Foot of the Town Hall and other venues. She urged the crowds “Put not your trust in princes, neither put in party politicians, and no account put it in Mr Winston Churchill.”

‘

On the day of the election, 25th January, Anna and other suffragettes followed Asquith as he visited polling stations. She warned people that a vote given to him was a vote given for women being sent prison. Petitions advocating votes for women were canvassed at all the polling stations. Anna complained that she was kicked and struck by the Liberal stewards saying ‘that was owing to the bad influence of Mr Asquith’ while at Tayport the women there flocked to the WFL standard and booed and hissed as he left the meeting. She described Mr Asquith as ‘a canting hypocrite and a humbug’

April 19th 1911 in the rooms of the Democratic Unionist Association Anna delivered a lecture to a large crowd on ‘The Women of Today’ –saying the goal society was moving towards was the realisation of the humanity of women not just her duty to marry and bring up children but to develop and use her god given talents.

The WFL were opposed to violent campaigning and in keeping with this organised a 400 mile walk from Edinburgh to London. It was led and organised by actress Florence Gertrude de Fonblanque. The peaceful protest set off on 12th October 1912 from Charlotte Square in Edinburgh marching down Princes Street and was sent off with the largest crowd the WFL had so far attracted. Anna spoke at the meeting saying the women’s movement was more than a passing phase. The aim of the walk was to gather signatures on route to a petition stating: ‘We, the undersigned, pray that the Government will make itself responsible for a Bill to give votes to women this session’. Their first stop on their walk was Musselburgh. The walkers were dressed in brown uniforms and brown felt hats with green cockades and heavy footgear, marching beneath a banner announcing the route and object of the march. They were escorted by a covered van.

Over fifty women marched on to Musselburgh where about 2000 people heard addresses from speakers. The public were attentive and on the whole friendly; however a few missiles were thrown including a bad egg and a few rotten apples. Anna was one of six women who completed the walk. They reported that the only unpleasant experience was in Peterborough where on 8th November a rally of ‘thousands’ of people was disrupted when the stage was rushed and large quantity fireworks were thrown at the speakers and they had to be accompanied out by the police.

The walkers entered London on the 16th November with a welcome parade, apparently over a quarter of a mile in length. It was attended by four or five thousand suffragettes both male and female who were led to Trafalgar Square amidst the stirring strains of ‘ See the Conquering Hero Comes’ and Women’s March composed by Dr Ethel Smyth; a friend of Emmeline Pankhurst. At Trafalgar Square a considerable crowd of people awaited. Mrs de Fonblanque took the petition to Downing Street with the cart containing the signatures; they were admitted although a police cordon had been drawn. At No 10 they were told the petition would be passed to Asquith.

The Prisoner’s Temporary Discharge for Ill Health Act, commonly referred to as the Cat and Mouse Act, was an Act of Parliament passed in Britain under Herbert Henry Asquith’s Liberal government in 1913 when Reginald McKenna was Home Secretary. Asquith was the MP for East Fife and fiercely opposed to women’s rights. The Women’s Freedom League posted a leaflet to “The Police Forces of Britain” urging the police to disregard the bill and to refuse to re-arrest Suffrage prisoners discharged for ill health. It was signed by Anna along with Charlotte Despard, E. Knight, Nina Boyle, A. Underwood and Kathleen Tanner. She also joined a deputation to McKenna along with Eunice Murray to complain about the conditions in jail for poor people. Eunice Murray was president of the WFL in Glasgow and often gave speeches alongside Anna and was the first women to stand for parliamentary election in Scotland.

While attempting to address a meeting at Hyde Park, London, on 5th May 1913 Nina Boyle, head the political and militant department of the Women’s Freedom League, and Anna, were arrested and taken to Crawford Place Police Station. They were jailed in Holloway for 14 days in default of payment of £20 for obstructing the free passage of the highway at Marble Arch, London. After being released, on 19th May, she attended the police station at Marylebone on Monday to bring to the attention of the authorities the conditions in the police van where prisoners of both sexes were conveyed and the behaviour of both men and women were violent, horrible and there were scenes of indecency.

Anna travelled to throughout England to give talks in the WFL horse-drawn caravan, and on one such trip to Thatcham, near Reading, she met Sidney Ashman whom she married in 1913 S1. In December 1918 she became president of the Reading Branch of the WFL

Anna Munro was a supporter of the temperance movement and president of the National British Total Abstinence Movement. After the First World War she became a magistrate in England and president of the Women’s Freedom League.

To find out the sources used in this research please contact localstudies.dunfermline@onfife.com