When the Adam Smith Theatre closed its doors for refurbishment in 2020, OnFife Museums were offered a collection of programmes, photographs and posters dating from the 1970s to present day. Amongst them material from the yearly pantomime. After a two-year break, our pantomime returns this Christmas at the Rothes Halls while the Adam Smith Theatre redevelopment continues. It wouldn’t be a pantomime without singing, dancing, slapstick comedy, audience participation (He’s behind you!) and of course the Dame with their extravagant costumes. Let’s take a dance down memory lane and look at the pantomimes of Christmas past at the Adam Smith Theatre.

In 1981, The Harman Brothers (known to many as The Chuckle Brothers) made their first of three appearances at The Adam Smith Theatre in Puss in Boots.

Poster for Puss In Boots featuring the Harman Brothers in 1981, FIFER:2022.0141

In 1982 they returned to play Policemen Yoo and Mee in Aladdin, alongside Danny O’Dea as Window Twanky and Dean Park as Wishee Washee.

LEFT: Poster for Aladdin in 1982, FIFER:2022.0141 RIGHT: The Harman Brothes (as Yoo and Mee) with Danny O’Dea (Widow Twanky), FIFER:2022.0095

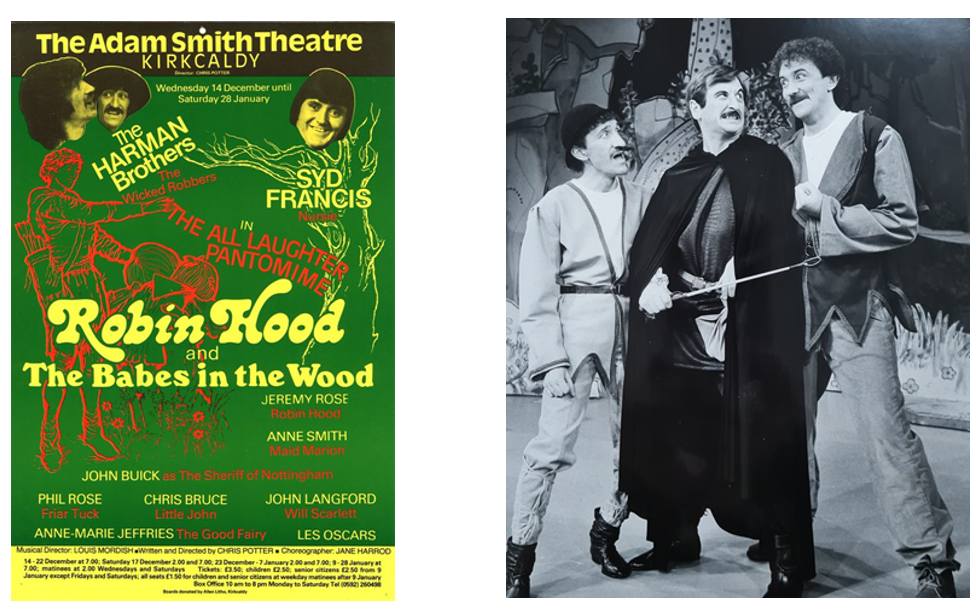

In 1983, The Harman Brothers’ third appearance – this time as the Wicked Robbers in Robin Hood and The Babes in the Wood.

LEFT: Poster for Robin Hood and The Babes in the wood in 1983, FIFER:2022.0141 RIGHT: The Harman brothers as Will and Wont with John Buick as the Sheriff, FIFER:2022.0096

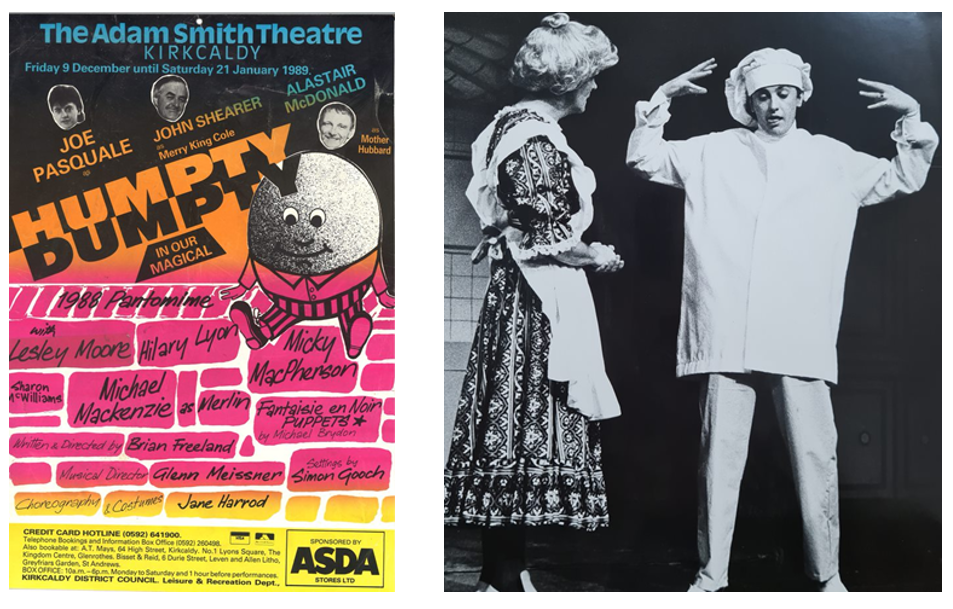

In 1988, another famous face took to the stage in an adaptation of the nursery rhyme, Humpty Dumpty, written and directed by Adam Smith Theatre’s General Manager Brian Freeland.

LEFT: Poster for Humpty Dumpty in 1988, FIFER:2022.0141 RIGHT: Joe Pasquale as Humpty Dumpty with Alasdair McDonald as Mother Hubbard, FIFER:2022.0100

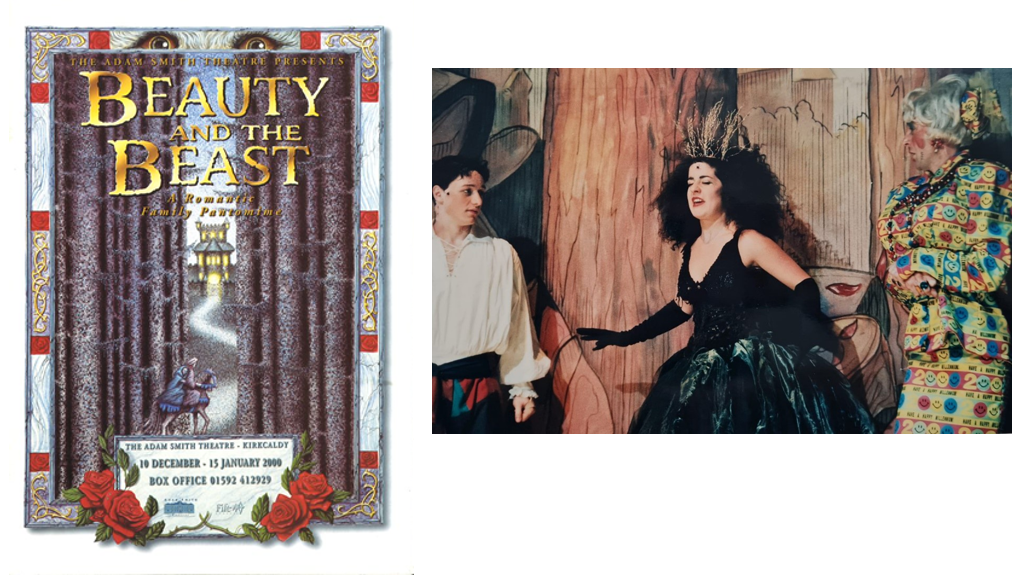

1999 saw James McAvoy as Bobby Buckfast the daft wee son of Betty Buckfast (Alan McHugh). Together Betty and Bobby worked together to protect Beauty (Fiona Steele) and see that she came to no harm from Sadista the Sorceress (Anita Vettesse).

LEFT: Cover of programme for Beauty and the Beast, FIFER:2022.0069 RIGHT: Bobby Buckfast (James McAvoy, left), Sadista the Sorceress (Anita Vettesse, middle) and Betty Buckfast (Alan McHugh, right), FIFER:2022.0104

What an amazing costume Dame Betty Buckfast is wearing above! Extravagant, bright and very on subject of the time with the 2000 detail. Dames’ costumes often reflect the local area and current matters. In this case marking the coming millennium.

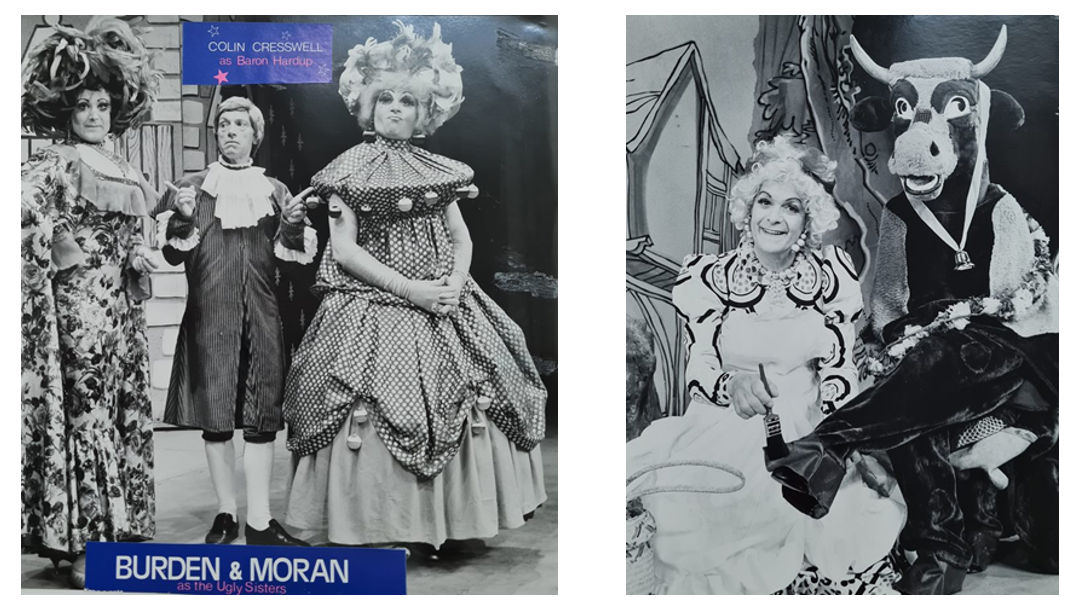

Here are some other pantomime characters for you to enjoy:

Mother Goose in 1975, FIFER:2022.0091

LEFT: Burden and Moran (the Ugly Sisters) with Colin Cresswell (Baron Hardup) in Cinderella in 1982, FIFER:2022.0094 RIGHT: Mary Lee as Jessie the Cook with cow in Dick Whittington in 1984, FIFER:2022.0097

LEFT: Nurse Polly Esther (James Murray) with Queen Semolina (Eileen McCallum) and King Tapioca (Martyn James) In Sleeping Beauty in 1995, FIFER:2022.0102 RIGHT: Alan McHugh as Jack’s Ma in Jack in the Beanstalk in 2000, FIFER:2022.0105

Programme for Mother Goose in 2015 featuring Billy Mack, FIFER:2022.0071

Programme for Jack and the Beanstalk in 2019, FIFER:2022.0071

The last pantomime to be held at The Adam Smith Theatre before it closed for its redevelopment was Jack and the Beanstalk.

What are your favourite memories of the Adam Smith Theatre pantos? Share them in the comments below! Happy panto season!

Memories of the time we were evacuated from Edinburgh to Cupar.

By Doreen Carmichael (nee Clapperton) dob 18/06/1928

I was eleven in the summer of 1939 when I heard talk of war. I knew about the first war of course, songs like Tipperary and Keep the Home Fires Burning were still played a lot on the radio alongside Lambeth Walk and Underneath the Chestnut Tree. This was way before Vera Lynn and the White cliffs of Dover. I knew about war from listening to adults or maybe from the Pathe News when I went to the cinema. I heard about soldiers coming home from Palestine and from the civil war in Spain. I’d read about Florence Nightingale and the Crimean war from a schoolbook. I didn’t know where any of these places were. I remember that air raid shelters were being built, one in the meadows and some people were having one in their own gardens. I thought that our family were safe because my Daddy was not going to be a soldier – he was away in the Royal Navy. Well, as I’ve said, I was only eleven. I don’t remember much about getting ready for evacuation day on September 1 st and I find that strange because our usual routine must have changed. I wonder how my mum managed, she was 34, she wouldn’t have wanted to leave her home. Her husband was miles away and she had to decide whether to evacuate or not. The powers that be were telling her that her children should be sent to the country for safety. She would also be worried about her mum who was on her own and a bit needy. Once the decision was made, clothes had to be packed and older children had to have their own bundle. We gathered at Sciences School in Edinburgh. A long line of mums, school children, toddlers, babies and teachers with bags, suitcases and gas masks. We walked to Newington Station and waited for the train. It was a “no corridor” train which meant we were locked in.

Our carriage was packed, my mum and her seven children, another mum with a young baby and a music teacher. We weren’t told where we were going and the train stopped often, not at official stations and we didn’t know why. The carriage got smelly and the baby’s nappy was changed. The train reached Cupar although I don’t remember arriving. My next clear memory is living with Mr and Mrs Lawson in a house at the top of Bishopgate and my young sister Joyce is with me. Mum and my other siblings were housed further down the road. I don’t remember which day we arrived in Cupar, but I do know that come the first Sunday morning we were told that war had been declared so that was the 3rd of September 1939. It was a nice sunny day and it seemed all the adults were out on the streets chatting to one another. The Lawsons were kind to us and I remember they had a young man staying with them. Joyce and I got out to play and we met other children. The name Louise Plunket comes to mind, I think she was a local girl and lived in a big house further down the road. We attended Castlehill Primary School. I would be in P7, I don’t remember much about that time and it was only much later that I realised how very important the P7 year is in a child’s development. I don’t remember how or why everything changed but it did. Mum and my younger siblings were now living with Mr and Mrs D J Bruce, at Mount Pleasant. I often wonder what Mum thought; it was a big house with oil lamps and an outside toilet. There was no hot water, the only tap was in the “lean to” kitchen. Joyce and I were still in Bishopgate and often walked up the South Road to see Mum. On one of these visits Mum noticed my head had nits and she wouldn’t let Joyce and I go back to Mrs Lawson’s which is why Mrs Bruce got landed with the whole Clapperton family. I later heard that Mr and Mrs Lawson didn’t want us back because she was pregnant. I hope all went well with that because they were nice people. So, there we were at Mount Pleasant with Mr and Mrs Bruce, mum and I, Lena, Joyce, Audrey and baby Percy. I remember Mr Bruce as being well into his eighties and in poor health. My brother Richard was billeted with a lady down the road, I only saw him if he was playing in the little front garden. Joyce and I were sure the lady in that house was a spy because she wore trousers. My other brother Jack was living at Tarvit Hill Mains Farm, along the road from Mount Pleasant and up a hill. I remember seeing him when he was coming back from school. Often over the years, I’ve felt great sadness at the thought of him making that journey and I don’t know why he and Richard were eventually sent to live somewhere in Springfield. So much was happening in our lives and I never knew why. Back to life in Mount Pleasant and whilst I can’t remember the right order of events I recall; mum went back to Edinburgh with baby Percy, Mr Bruce died and the Thompsons, Dorothy, Robert and Helen came to live with us. The Thompsons came from West Newington Place, Edinburgh. Later in life when living near there I met many people who remembered them. Mr David James Bruce was quite tall and a little stooped, in his eighties and not in the best of health. I’ve often wondered what he thought about all of us being billeted in his house. I wonder, did he and Mrs Bruce have any say in the matter? He died soon after we arrived. I understand that Mount Pleasant had been his family home and was told that when his father was dying the road in front of the house was covered with straw so that it was quiet for him. Mrs Bruce must have been in the house because, as she told me, she nursed Mr Bruce’s mother. The details of that were pretty awful, it was the first time that I had heard the word cancer. I don’t know what Mr Bruce did in his working life and I wonder if he always spent a lot of his time gardening. The garden was well laid out with fruit trees, apples, plums, and pears. Soft fruits such as black and redcurrants and strawberry beds, also artichokes (I’d never heard of them).

There was always lots of lettuce and vegetables. I remember learning how to store apples, each apple was half wrapped in newspaper and laid with a little space between them on a shelf and in a dark place. Mrs Sarah Henrietta Bruce was the daughter of Walkers the bakers in Dundee and she spoke of a sister who live in Ballater. Mrs Bruce was a little old lady, under 5 feet and very bow legged, her hair was snowy white and as far as I can remember it was always neat. There were some out houses at the back of the main house and one was used to store food for the hens. The hen house was at the top of the back field that sloped down to the river Eden. I remember mixing food for the hens and spreading it over the grass, soon the hens would be pecking all round me. Another memory is being sent to the hen house to bring in eggs. They were usually big and warm. Some of these eggs were sold, some were pickled in waterglass and, of course, with 6 children and one adult many eggs were eaten. (In general eggs were rationed to one a week or one a fortnight.) Did we ever eat one of our hens? I don’t know, but I do remember being told that a particular bird was past laying. I don’t remember much about what we got to eat but a very clear memory is that the dining table had to be properly set, one of us would be sent to pick flowers for the table and just like at home in Edinburgh, we had to ask permission to leave the table. As I’ve already said the kitchen was a ‘lean to’ at the back of the house. It had an ancient gas cooker, a stone sink and one cold water tap. Wet dishes were placed in a wooden rack above the sink. I can’t remember what was used to clean dishes; it certainly wasn’t fairy liquid. The floor was stone, uneven and always cold. The place had a smell that I came to know was mice, but I don’t recall ever seeing one of the little creatures. All of us washed at that sink and that is probably why I remember it always being so cold. What I don’t know is where the gas came from, I never saw a bottle in the kitchen and for a long time we were using oil lamps. As for the wireless, I’m guessing it must have been on an accumulator. At home in Edinburgh, we used accumulators before we got electricity. We must have settled ok as I don’t remember any major upsets. Time passed and I went to Bell Baxter High School. Dorothy Thomson will have done also but I don’t remember. On Sundays, some of us went to church (St James Episcopal) three times as I remember; Early morning service, Sunday school and the evening service. Mrs Bruce had some of us confirmed in the church. Joyce and I wore our Guide uniforms and some of the other youngsters wore the more usual lovely white outfits. Sunday evenings, we listened to the news on the wireless. We heard how many German planes had been shot and how many of ours were lost. I’m sure that there must have been more news, but the plane count was what we waited for. The programme ended with playing the anthems of different countries Mrs Bruce and all of us children stood to attention for that. I’m sure I didn’t dwell on “we are at war” but some events would remind me. When the siren sounded Mrs Bruce would get us all downstairs, then we would put our gasmasks on and sit with her on her bed until the all-clear sounded. The masks were so uncomfortable, it must have been so awful for the wee ones. A nicer memory is going out for a walk in the dark and watching the searchlights playing across the sky, beautiful really. I’m not sure how this came about, it might have been arranged by the church. A group of us children were introduced to some Polish soldiers. I do remember chatting to a young soldier who told me he’d had to leave his home just as I had. He gave me a book about Warsaw and an eagle badge, I would have been about 12. I don’t know what happened to those lovely gifts. Thinking about South Road again, across the road from us the Robertson sisters lived. I don’t remember meeting them, but I was told that their afternoon tea was bread and butter with jam, or bread and butter with cake. Jam or cake. The Gordon sisters lived just up from the Robertsons. My young sister Joyce was often in their company. Joyce was friends with another family and I think their name was Nash. The Nash house was a bit up the road from us, it was a big house and close to the river Eden. I’m not sure if the family Nash were American or had just come from America. Still on the South Road, up a hill was Tarvit Hill Farm (my brothers were billeted there for a short time) and not far away is Tarvit Hill House. I think it may be a hospice now. During the war it was the home of our Guide Captain, Miss Elizabeth Sharp. I read some years later that she became head guide for Scotland. She died quite young. Our Guide group met in Tarvit House and that was just up from the railway station. The grounds there were absolutely beautiful, a big garden with very many old trees. The garden needed weeding and some of us guides tried to help with that. Some memories are so very clear. During my time at Bell Baxter, I was chosen to present flowers to a visiting dignitary. I don’t know what the occasion was, but the sweet peas I carried were beautiful. I also remember our one and only visit to a cinema whilst in Cupar, Dorothy Thomson and I saw a Gracie Fields film. I don’t know what the film was, but I knew that Gracie was no longer popular because she married Monty and went to America. (I must have heard adults discussing this before the war).

Over the years I kept in touch with Mrs Bruce and in 1950 invited her to my wedding. She was unable to come but sent a lovely present to me at my place of work, Elliot’s Bookshop in Princes Street. I hope that I wrote to thank her, my mum was very ill in hospital at the time and some things just didn’t get done as they should. I went to Cupar in 1951 and found that Mrs Bruce was well and looked just as she had done in the early forties. We walked in the garden for a while and had our pictures taken. I went back in the summer of 1953 and found Mrs Bruce was in bed, she didn’t say what was wrong however she seemed content with her wireless and a paper. There were other people living in the house and I suppose that they were looking after her. Later in 1953 my husband and I went to live in Nigeria. I wrote to Mrs Bruce but didn’t hear back. During the 80’s my sister Joyce and I visited Cupar on a number of occasions. We would walk from the railway station up South Road, peek over the wall to see “our” garden and remember our times there. We couldn’t understand what had become of Tarvit House although I now believe that it was demolished and the land used for new housing. I do hope the builders managed to keep some of the lovely trees in place.

And so to the present time, 2022. In August my son, his partner and I took a trip to Falkland Palace and after we went on to Cupar. We went up the South Road, but it was pouring with rain and so didn’t get out for a walk. From the car we could see the fruit trees, laden with apples and plums. Would they be the trees that were there in the thirties? I don’t know. Once back home, I was thinking about Mount Pleasant and wondered if the present owners knew of its evacuee history, so I set myself the goal of finding out. It turns out that the lady who now lives in that house had heard about evacuees and had been looking for information. She wrote me a lovely letter and I hope I will be meeting her at some time. Having shared my exploits with my good friend Sheila (a wizard on the computer), she kindly trawled the archives and found the obituaries for both Mr David Bruce in The Courier and Advertiser (02/02/1940) and Mrs Sarah Bruce in The Fife Herald and Journal (07/09/1955). I see now from Mrs Bruce’s obituary that sadly she was most probably in Methilhaven Care Home when I wrote to her from Nigeria in 1953 hence, I didn’t hear back. I wonder how it is that not a hint of Mr and Mrs Bruce’s fascinating history was known to any of us children when we lived with them?

Doreen Carmichael, August 2022

ON at Fife Archives

Index to CASTLEHILL School Evacuees admission register

This index was created for OnFife Archives by David Ritchie, volunteer. This is a name index to a register of evacuees who attended Castlehill School in Cupar.

Castlehill School kept a separate register for evacuee children who were admitted to the school between 1939 and 1945.

I/A/3/206 Clapperton, Audrey – Evacuee 13/09/1939

dob – 21/09/1932 Parent/Guardian – Clapperton, Percy Cupar Address – Mt Pleasant, South Road Previous School – Sciennes Date of Leaving – 30/03/1942 Destination – Rothesay

I/A/3/53 Clapperton, Doreen – Evacuee 13/09/1939

dob – 18/06/1928 Parent/Guardian – Clapperton, Percy Cupar Address – c/o Lawson, 44 Bishopgate Previous School – Sciennes Date of Leaving – 12/07/1940 Destination – Bell Baxter

I/A/3/106 Clapperton, John – Evacuee 13/09/1939

dob – 30/09/1939 Parent/Guardian – Clapperton, Percy Cupar Address – c/o Taylor, Tarvithill Farm Previous School – Sciennes Date of Leaving – 03/01/1940 Destination – Springfield

I/A/3/146 Clapperton, Joyce – Evacuee 13/09/1939

dob – 19/03/1931 Parent/Guardian – Clapperton, Percy Cupar Address – South road Previous School – Sciennes Date of Leaving – 30/03/1942 Destination – Rothesay

I/A/3/321 Clapperton, Richard – Evacuee 06/11/1939

dob – Parent/Guardian – Clapperton, Percy Cupar Address – [not given] Previous School – ‘Ent. Infants’ (entry date indicated as ‘re-admission’) Date of Leaving – 18/12/1939 Destination – Springfield

`HORSES` BY MIMA ROBERTSON, born 1901

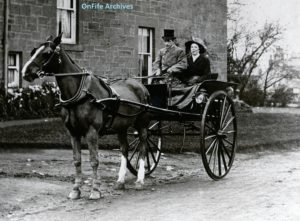

Looking back on my childhood it seems that horses and ponies played an important part in it. John Goodall had a large livery-stable, which provided cabs for the station – luggage on the roof – carriages or landaus for special, with sometimes two horses, gigs and pony-carts, hearses with handsome black horses decked out with black plumes. Father used to hire a Shetland pony for me to ride when I was about five but that did not last long as Mother was afraid I would fall off and injure myself. (Later I got a bicycle on which I performed far more hazardous feats – tramlines made cycling dangerous as it was easy to catch ones front-wheel in one when speeding down the steep Townhill Road).

But my great delight was when Father summoned a `trap` from Goodall`s, perhaps in a late summer afternoon when he had returned from the office. This was a lightweight vehicle with two high wheels and a seat for two perched up behind the dashboard and usually a mettlesome animal between the shafts. With a rug round my black-stockinged legs and my feet not touching the floor I would sit by Father`s side while he, expertly handling the reins and the slender whip, would take us out into the country, down to Limekilns perhaps and round by Saline. Then, as there was very little traffic on the roads, I was allowed to experience the thrill of driving the horses myself, learning to hold the reins properly as we went along at a smart pace that only slackened when climbing a hill. That was a real treat and I`m sure Father enjoyed it as much as I did.

Then there were the tradesmen`s horses, tramping down the avenue to the yard where they took sugar from me while the baker – Allans, with a very smart van high-sided with gold lettering on red paint – or the butcher or the grocer had a chat with the housemaid at the back door. Our Doctor Fleming who had a small brougham in winter, an open Victoria in summer, also made frequent calls. His coachman, Peter McArthur, was a firm friend of mine and he sometimes took me off for a turn round the Park while the doctor was taking Mother`s pulse. He was never in a hurry and never complained when we kept him waiting. Changed days indeed!

Dunfermline Cleaning gang with horses

Ashes and house-refuse were collected by another horse-drawn vehicle belonging to the town corporation from the stone-built rubbish-container at the top of the garden between the greenhouse and the wash-house. I met other horses on my way through the town and often stopped for a chat as they stood patiently by the pavement. There were always two or three horse-drawn cabs waiting at the Lower Station – in those days Dunfermline was an important railway-junction and one could take trains to Edinburgh, Perth, Stirling, Alloa, St. Andrews, etc. at frequent intervals. The bus that went to Limekilns and Charlestown was horse-drawn and for some years after the `14 War could be found waiting at the Glen gates near the Abbey.

When I was about eleven Mother and I stayed one summer holiday at the Athol Palace, Pitlochry, and went on a wagonette to Braemar. There were four horses, passengers inside and out, and when we reached the Devil`s Elbow everyone except the driver had to walk up – and later down – the steep curves of the road. I was on the box beside the driver – trust me! – and was allowed the honour of holding the reins for a short spell. Driving four horses, spanking along – I have never forgotten it.

Thanks to Cupar Local Studies for the majority of the photographs.

NOTE ON MIMA ROBERTSON

Mima Robertson was born in 1901 to John Whyte Robertson and his wife Jemima Taylor and was baptised Jemima Simpson Taylor Robertson. Her father worked for the family firm of Hay and Robertson, linen and cotton manufacturers, and her mother was the daughter of John Taylor a West Indian merchant. The couple already had two children, Margaretta born in 1889 and William born in 1893. In 1891 the family lived

at Dunsloy Villas, New Row, in 1901 at 3 Comely Park Place, and from about 1906 at Witchbrae, Townill Road. Witchbrae had been built in about 1860 for the Hay family and was advertised for sale in 1926 as a `fine dwelling house` set in two acres of grounds with excellent views to the south. It was lit by electricity, had several public rooms, six bedrooms, bathrooms, two bedrooms and a bathroom for the maids and numerous utility rooms and outbuildings. The Robertsons kept at least three female servants as well as the outdoor staff.

After an early education at Roseberry House, a private school in the Masonic Lodge, New Row, Miss Robertson was sent to boarding-school. She was so unhappy there that she was brought home to be educated by a governess. The governess, apparently an inspiring teacher, had taught classics at a boys` school and now she taught Latin to Mima, who found it stood her in good stead in her writing.

Mima had written stories from early childhood and when she was 19 received her first payment, 20 shillings from Punch for a humorous article. She loved to travel especially to Brittany and in 1926 she had a story called A Change of Air, set between Brittany and Dunfermline, accepted by a London agent and publishers, who changed the title to The Leopard`s Skin. Other novels with a Dunfermline connection were The Sport of Circumstance and Bitter Bread , while After Stormy Seas was again based in Brittany and Music in the Air in Gottland, the Baltic island, also a holiday destination.

Then followed two historical novels under the name `Alison Taylor`, Alison because it was Scottish and Mima liked it better than her own, and Taylor, her mother`s maiden name. For a change, Evil Enchantment of 1930 was a psychological thriller which she felt would have made a good film.

In the early 1930s when her writing had become a real necessity Miss Robertson was invited to contribute serials to the magazines run by Leng Publications of Dundee, particularly the People`s Friend. She was associated with the People`s Friend for some 40 years and found that writing to order involved a strict routine unlike the free-and-easy hours she had been used to. She continued to write novels and in 1953 published The Castilian, a historical novel about William Kirkcaldy of Grange, who was executed for his attempt to hold the besieged Edinburgh Castle for Mary Queen of Scots.

Mima Robertson had talents other than writing. She played first violin in Dunfermline Amateur Orchestra and was an artist and a needlewoman. She captained the Dunfermline Tennis Club ladies and became President of the Dunfermline Soroptimists. Miss Robertson never married and during the depression of the 1930s, when the family fortunes plummeted, the income from her writing became even more important. From Witchbrae, Mima and her parents moved to 9 Cameron Street where her mother died in 1944 and her father in 1959. Miss Robertson then moved to a flat at 15 Cameron Street and it was here in 1979 that she wrote her magnum opus Old Dunfermline and where she died in 1985 aged 83.

In Miss Robertson`s article on horses, the house referred to is Witchbrae and one of the six bedrooms probably became the schoolroom and what Miss Robertson called `My Room`. `Neil` was the gardener Neil McLean, and `Miss Nimmo` possibly the `nurse and sewing maid for one girl 4½ years` that Mrs. Robertson advertised for in 1906. Or perhaps `Miss Nimmo` was the governess who did sewing as well. The sources for this biography come from various on-line genealogy and newspaper sites, from Dunfermline Press, March 13 1970 (largely reproduced in Hugh Walker`s The History of Hay and Robertson, 1995) and Miss Robertson`s papers, which include (possibly unpublished) stories and plays, and are currently being archived at Dunfermline Carnegie Library but are not yet catalogued.

Image: A pattern book. KIRMG:1992.0267

This is a pattern book, produced by Nairn’s of Kirkcaldy in 1930. It contains full-colour images of the linoleum designs produced by the company in that year, and would have been made available for customers to browse before they made their selection.

We have over fifty of these in our collections, dating from the mid 19th century to the 1960s. As we continue to accession the Forbo Factory archive, modern brochures join this collection to allow us to view linoleum as potential customers have for 150 years. While the way in which linoleum is made has changed little in that time, the styles sought after by and available to customers have changed dramatically.

20th and 21st century designs tend to be more general in their function; today, Forbo brochures showcase marbled-pattern linoleums in a kaleidoscope of colours, fit for every style and season.

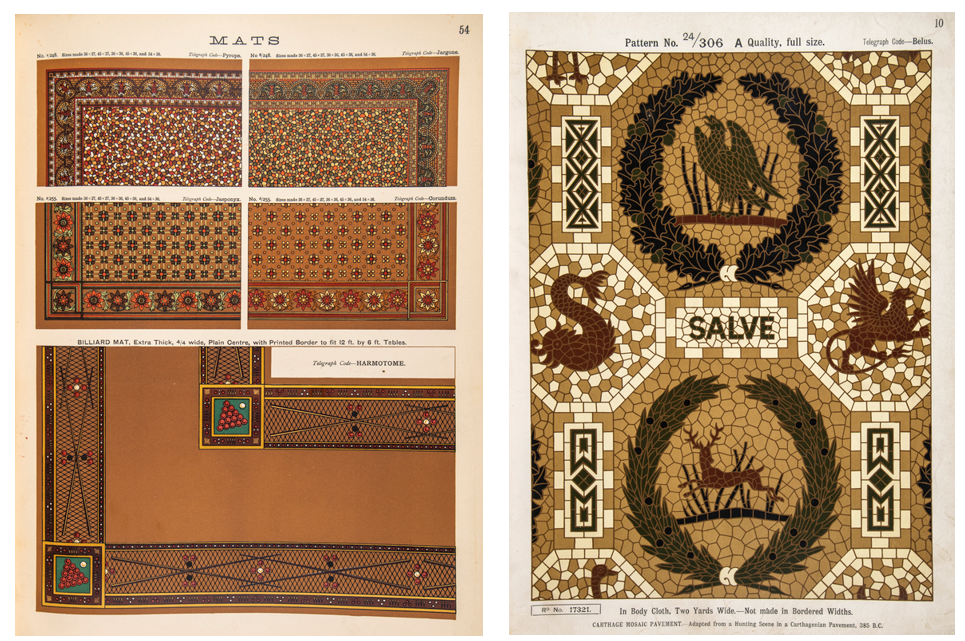

However, our 19th century pattern books contain designs created with specific spaces in mind. One features a border of cues and billiard balls for a games room, and the inclusion of the word ‘Salve’ (the Latin for ‘welcome’) in this classical design points towards its being intended for an entrance hall. The room in the house which seems to have generated the most elaborate space-specific designs, however, is the nursery.

Images: Two pages from FIFER:2022.0150.

Today, we associate linoleum in the home mainly with kitchens and bathrooms; in the 19th and early 20th centuries, it (along with its forerunner floorcloth) could be found in any room. So, with all these rooms to choose from, why designs intended specifically for the nursery? This trend was dependent on two key social developments in the late Victorian period. The first, as strange as it sounds, was the invention of childhood.

Prior to this time, the common consensus was that there was nothing special about being a child. Children wore miniature versions of adults’ clothes and contributed economically to the family by working. They were seen as miniature versions of the grown-ups they would become – with any variations from adulthood being seen as passing nuisances.

In the mid 19th century however, improving economic conditions and the rise of the middle-classes meant that it was not always essential for children to work to support a household. Life before adulthood became associated with leisure, play, and innocence. Rather than a temporary state of smallness, childhood became something to be cherished and protected.

Image: Portrait of Ian Couper Nairn, by Harrington Mann. KIRMG:383. The children of the Nairn family – Kirkcaldy’s original linoleum manufacturers – had their portraits painted in 1899. They would’ve been among the first generations of children raised according to new notions of childhood. In this portrait, we see Ian Couper Nairn standing in an interior – perhaps a glimpse into his linoleum floored nursery?

This same economic improvement brings us to the second change: a greater separation between work and the home.

Due to British imperialism, this period was marked by accelerated industrialisation. As the shape of work changed, so too did the shape of the workplace. Towns and cities across the country became filled with factories and warehouses – transforming raw materials and storing finished goods extracted from overseas territories – and offices to manage these global businesses. Britain grew rich by travelling beyond its shores, exploiting the people and lands of its acquired territories. As a result of this, middle-class families were able to mirror this expansionist impulse, travelling beyond their homes to new, modern workspaces.

On a practical level, this meant that many middle-class Briton’s now found themselves with more space in their houses. So, as childhood became a precious, protected time in a person’s life, the home became a special place reserved for leisure, relaxation and the family (though each of these privileges was dependent on being born into a family wealthy and stable enough to afford them). The extra space in the home therefore naturally became a place exclusively reserved for children: the nursery.

This meant that there was suddenly a new market to be catered to. However, the idea that children will have at least some say in how their spaces are decorated is a relatively new one. So – while children would undoubtedly have enjoyed them – these patterns were primarily designed to cater to the adults who would be purchasing them.

More specifically, they appealed to women. Though men’s work had left the home, women’s labour remained. As the home began to change shape (and size) in response to these social and economic changes, a new task emerged for the middle-class Victorian – the creation and cultivation of a tasteful interior.

Whereas once, home furnishings beyond the functional and comfortable were the preserve of the upper-classes, middle-class homes were now also expected to be finished in the latest fashion. From the 1860s, ‘homemaking’ became a respectable pastime for well-to-do women, joining the ranks of other sanctioned hobbies such as album-making, crafting faux flowers, and fern collecting. Each of these hobbies was seen as distinctly feminine, and as exercises by which women could cultivate their finest ‘womanly’ traits and, by extension, their morality. They required quiet, rewarded perfectionism and patience, and encouraged the contemplation of the meek and delicate.

Homemaking fulfilled a similar function, but with a crucial difference. Whereas these other crafts resulted in small, hidable products, home décor was a comparatively public medium for self-expression – or, more accurately then as today, an expression of the self one wished to impress on others. An ill-pasted page in an album could be avoided; an unkempt, poorly appointed room was for all to see.

Alongside creating a home which was fashionable and comfortable, therefore, the middle-class Victorian woman also had to make sure her home décor choices conveyed her unblemished character. This meant, of course, that it had to be clean.

In the 19th century cleanliness was truly next to godliness; any evidence of dirt or wear was surely a sign of loose character. Here then, the Victorian woman was in a bind. To be a ‘good’ wife, it was expected (perhaps even necessitated in an era with paltry access to contraception) that she have children. However, that goodness would be easily undermined by mess which naturally accompanied those children. The solution to this problem was – you guessed it – linoleum.

Images: This advert for Forshaga linoleum (left; FIFER:2022.0201) touts the floorcoverings virtues in relation to the body of the housewife. In Kirkcaldy (right, TEMP:2011.4263), a slightly different tactic was used to emphasise linoleum as a labour-saving innovation. This advert by Nairn’s impresses that its products are dry-wipe using the cute metaphor of puppies and kittens rather than the unpleasant reality of the messes all young animals – including nursery-bound humans – make.

The hygienic qualities of linoleum have always been central to its appeal, and the same was true in the 19th century. Linoleum was quicker and easier to clean than traditional floorcoverings, and this was exploited in adverts, such as this one produced by Swedish manufacturers Forshaga.

The stress of cleaning a wooden floor is obvious in the face of the woman scrubbing them who – with her muscular arms and messy hair – is coded as working-class. The leisured middle-class homemaker on the right does not have to spoil her appearance or her delicate, idealised figure with such labour: she has linoleum. Linoleum, therefore, was a good and proper thing for Victorian women – indeed, it would help them preserve their status by ensuring that their homes and bodies conformed to class and gender norms.

If dirt and mess was a visual sign of moral decay, noise of any kind warned the ear of bad character. Here too, linoleum had the edge over wooden, stone or tiled floors. Linoleum – particularly thicker and more expensive varieties such as cork carpet – muffled the sounds of toys bounced, dragged or skittered across it (while also resisting any marks they might make). It was also more forgiving on toddling, crawling bodies – which (theoretically) meant less crying. Childhood was precious – but children were still meant to be seen and not heard.

Once a Victorian woman was certain she had a clean and moral home, she had to turn her mind to the future – and that meant education. It was up to her to impress both knowledge and upright values on her young charges – and linoleum – it was hoped – would shape the futures of the small humans who walked on it.

Image: This cork carpet design, dating from 1892, shows children playing in an imagined countryside. At a time when the industrialisation which made floorcoverings like these and the nurseries which housed them possible, there was a strong popular taste for images of a rural life which was imagined as simpler and more innocent than modern cities – just as childhood became seen as simpler and more innocent than adulthood. FIFER:2022.0174

The floorcoverings designed for nurseries served as teaching tools as well as decoration. Writer Samuel Smiles stressed the importance of visible examples of good behaviour, insisting that these were far more impactful than mere explanation. More was at stake than just a peaceful homelife; for Smiles, “the nation [came] from the nursery” – the health and strength of the country depended on children knowing clearly what was expected of them.

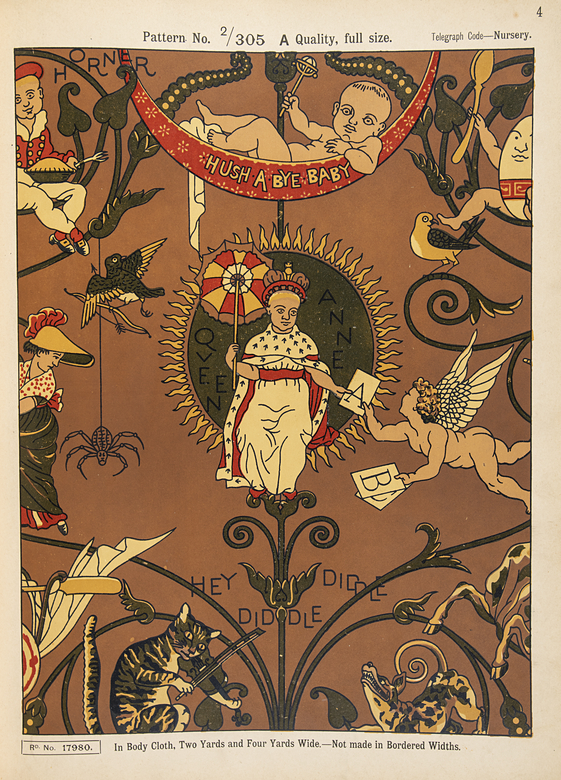

To do this, floorcovering designs borrowed heavily from other media created with children in mind. Illustrated books produced by English artists Kate Greenaway and Walter Crane clearly had a strong influence on the designs in our collections.

The design above clearly mimics Greenaway’s style. It epitomises the idealised childhood of the time – well-behaved, flaxen-haired children frolic unsupervised in a colourful, pastoral idyll. Their world is unblemished by signs of work or modernity; their play is neat and innocent. Children surrounded by these designs surely could not help but follow their example, as Smiles hoped.

Image: In a pattern book produced by the Kirkcaldy Linoleum Company, 1876 – c.1900. Though the colours differ from Crane’s wallpaper, the rest of the design is identical. Though most of these nursery rhymes have stood the test of time, the central song ‘Letters to Queen Anne’ appears to have faded away from the nursery in the 20th century. FIFER:2022.0150

Another theme favoured by interior design writers, consumers and manufacturers alike was nursery rhymes. This design by Walter Crane was commissioned by Jeffrey and Co. in 1876; examples of this paper – both in a predominantly blue and yellow colour scheme – survive in the collections of the V&A and the Cooper Hewitt Museum. We don’t know exactly when it was adapted by the Kirkcaldy Linoleum Company, but the fact that it was is testament to its popularity.

Pictures in rooms used by children served the same purpose then as they do now: to provide bright and colourful memory aids to assist learning and lend rhythm to group games and activities. Children living in industrial cities might not venture into a Greenaway-esque countryside, but they would still learn to tell a cow from a spoon in a well-appointed Victorian nursery, as well as maybe learning a bit of the alphabet.

All of this together meant that, from the mid-19th century, the physical reality of the Victorian home – its fixtures, fittings and decoration – was seen as an essential to the moral, intellectual, and physical health of the nation and its Empire. While the interior home was important, this project started from the bottom up – both in terms of beginning in childhood, and beginning with an appropriate floorcovering. Given the high stakes, is it any wonder linoleum companies designed products specifically for the nursery?

_________

This blog was written by Lily Barnes, curator working on the linoleum project Flooring the World (2022-2024). Flooring the World is a two-year project exploring the history of the Fife linoleum industry. It is funded by the Esmée Fairbairn Collections Fund, which is run by the Museums Association, funding projects that develop collections to achieve social impact.

If you have any questions or information you’d like to share, you can get in touch at lino@onfife.com