Image: A pattern book. KIRMG:1992.0267

This is a pattern book, produced by Nairn’s of Kirkcaldy in 1930. It contains full-colour images of the linoleum designs produced by the company in that year, and would have been made available for customers to browse before they made their selection.

We have over fifty of these in our collections, dating from the mid 19th century to the 1960s. As we continue to accession the Forbo Factory archive, modern brochures join this collection to allow us to view linoleum as potential customers have for 150 years. While the way in which linoleum is made has changed little in that time, the styles sought after by and available to customers have changed dramatically.

20th and 21st century designs tend to be more general in their function; today, Forbo brochures showcase marbled-pattern linoleums in a kaleidoscope of colours, fit for every style and season.

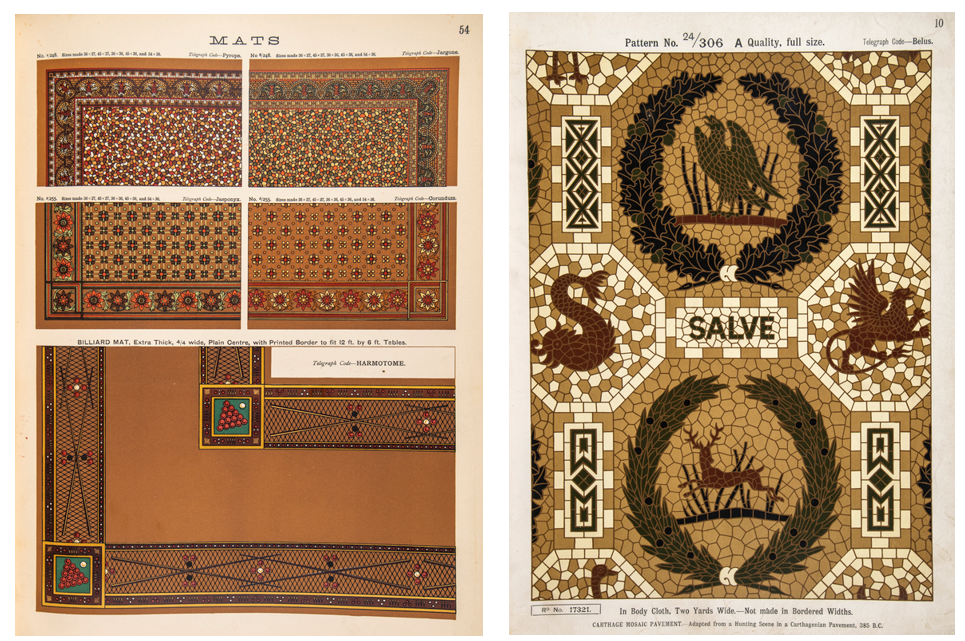

However, our 19th century pattern books contain designs created with specific spaces in mind. One features a border of cues and billiard balls for a games room, and the inclusion of the word ‘Salve’ (the Latin for ‘welcome’) in this classical design points towards its being intended for an entrance hall. The room in the house which seems to have generated the most elaborate space-specific designs, however, is the nursery.

Images: Two pages from FIFER:2022.0150.

Today, we associate linoleum in the home mainly with kitchens and bathrooms; in the 19th and early 20th centuries, it (along with its forerunner floorcloth) could be found in any room. So, with all these rooms to choose from, why designs intended specifically for the nursery? This trend was dependent on two key social developments in the late Victorian period. The first, as strange as it sounds, was the invention of childhood.

Prior to this time, the common consensus was that there was nothing special about being a child. Children wore miniature versions of adults’ clothes and contributed economically to the family by working. They were seen as miniature versions of the grown-ups they would become – with any variations from adulthood being seen as passing nuisances.

In the mid 19th century however, improving economic conditions and the rise of the middle-classes meant that it was not always essential for children to work to support a household. Life before adulthood became associated with leisure, play, and innocence. Rather than a temporary state of smallness, childhood became something to be cherished and protected.

Image: Portrait of Ian Couper Nairn, by Harrington Mann. KIRMG:383. The children of the Nairn family – Kirkcaldy’s original linoleum manufacturers – had their portraits painted in 1899. They would’ve been among the first generations of children raised according to new notions of childhood. In this portrait, we see Ian Couper Nairn standing in an interior – perhaps a glimpse into his linoleum floored nursery?

This same economic improvement brings us to the second change: a greater separation between work and the home.

Due to British imperialism, this period was marked by accelerated industrialisation. As the shape of work changed, so too did the shape of the workplace. Towns and cities across the country became filled with factories and warehouses – transforming raw materials and storing finished goods extracted from overseas territories – and offices to manage these global businesses. Britain grew rich by travelling beyond its shores, exploiting the people and lands of its acquired territories. As a result of this, middle-class families were able to mirror this expansionist impulse, travelling beyond their homes to new, modern workspaces.

On a practical level, this meant that many middle-class Briton’s now found themselves with more space in their houses. So, as childhood became a precious, protected time in a person’s life, the home became a special place reserved for leisure, relaxation and the family (though each of these privileges was dependent on being born into a family wealthy and stable enough to afford them). The extra space in the home therefore naturally became a place exclusively reserved for children: the nursery.

This meant that there was suddenly a new market to be catered to. However, the idea that children will have at least some say in how their spaces are decorated is a relatively new one. So – while children would undoubtedly have enjoyed them – these patterns were primarily designed to cater to the adults who would be purchasing them.

More specifically, they appealed to women. Though men’s work had left the home, women’s labour remained. As the home began to change shape (and size) in response to these social and economic changes, a new task emerged for the middle-class Victorian – the creation and cultivation of a tasteful interior.

Whereas once, home furnishings beyond the functional and comfortable were the preserve of the upper-classes, middle-class homes were now also expected to be finished in the latest fashion. From the 1860s, ‘homemaking’ became a respectable pastime for well-to-do women, joining the ranks of other sanctioned hobbies such as album-making, crafting faux flowers, and fern collecting. Each of these hobbies was seen as distinctly feminine, and as exercises by which women could cultivate their finest ‘womanly’ traits and, by extension, their morality. They required quiet, rewarded perfectionism and patience, and encouraged the contemplation of the meek and delicate.

Homemaking fulfilled a similar function, but with a crucial difference. Whereas these other crafts resulted in small, hidable products, home décor was a comparatively public medium for self-expression – or, more accurately then as today, an expression of the self one wished to impress on others. An ill-pasted page in an album could be avoided; an unkempt, poorly appointed room was for all to see.

Alongside creating a home which was fashionable and comfortable, therefore, the middle-class Victorian woman also had to make sure her home décor choices conveyed her unblemished character. This meant, of course, that it had to be clean.

In the 19th century cleanliness was truly next to godliness; any evidence of dirt or wear was surely a sign of loose character. Here then, the Victorian woman was in a bind. To be a ‘good’ wife, it was expected (perhaps even necessitated in an era with paltry access to contraception) that she have children. However, that goodness would be easily undermined by mess which naturally accompanied those children. The solution to this problem was – you guessed it – linoleum.

Images: This advert for Forshaga linoleum (left; FIFER:2022.0201) touts the floorcoverings virtues in relation to the body of the housewife. In Kirkcaldy (right, TEMP:2011.4263), a slightly different tactic was used to emphasise linoleum as a labour-saving innovation. This advert by Nairn’s impresses that its products are dry-wipe using the cute metaphor of puppies and kittens rather than the unpleasant reality of the messes all young animals – including nursery-bound humans – make.

The hygienic qualities of linoleum have always been central to its appeal, and the same was true in the 19th century. Linoleum was quicker and easier to clean than traditional floorcoverings, and this was exploited in adverts, such as this one produced by Swedish manufacturers Forshaga.

The stress of cleaning a wooden floor is obvious in the face of the woman scrubbing them who – with her muscular arms and messy hair – is coded as working-class. The leisured middle-class homemaker on the right does not have to spoil her appearance or her delicate, idealised figure with such labour: she has linoleum. Linoleum, therefore, was a good and proper thing for Victorian women – indeed, it would help them preserve their status by ensuring that their homes and bodies conformed to class and gender norms.

If dirt and mess was a visual sign of moral decay, noise of any kind warned the ear of bad character. Here too, linoleum had the edge over wooden, stone or tiled floors. Linoleum – particularly thicker and more expensive varieties such as cork carpet – muffled the sounds of toys bounced, dragged or skittered across it (while also resisting any marks they might make). It was also more forgiving on toddling, crawling bodies – which (theoretically) meant less crying. Childhood was precious – but children were still meant to be seen and not heard.

Once a Victorian woman was certain she had a clean and moral home, she had to turn her mind to the future – and that meant education. It was up to her to impress both knowledge and upright values on her young charges – and linoleum – it was hoped – would shape the futures of the small humans who walked on it.

Image: This cork carpet design, dating from 1892, shows children playing in an imagined countryside. At a time when the industrialisation which made floorcoverings like these and the nurseries which housed them possible, there was a strong popular taste for images of a rural life which was imagined as simpler and more innocent than modern cities – just as childhood became seen as simpler and more innocent than adulthood. FIFER:2022.0174

The floorcoverings designed for nurseries served as teaching tools as well as decoration. Writer Samuel Smiles stressed the importance of visible examples of good behaviour, insisting that these were far more impactful than mere explanation. More was at stake than just a peaceful homelife; for Smiles, “the nation [came] from the nursery” – the health and strength of the country depended on children knowing clearly what was expected of them.

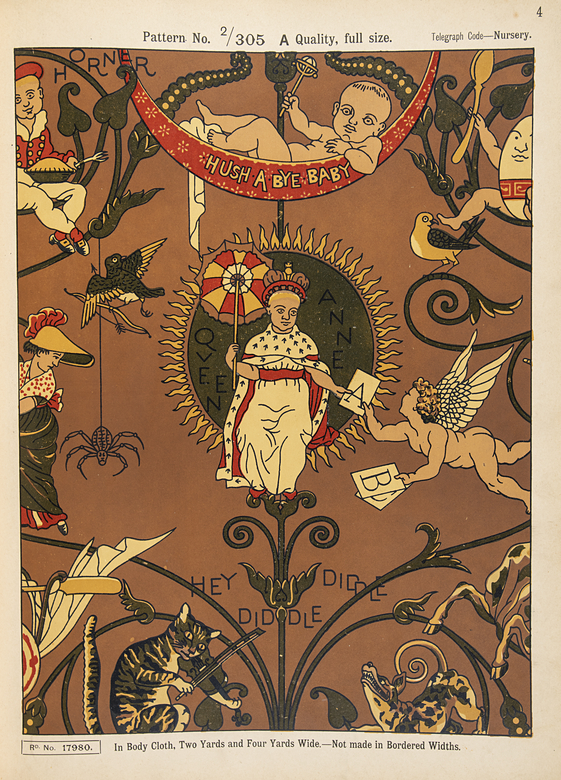

To do this, floorcovering designs borrowed heavily from other media created with children in mind. Illustrated books produced by English artists Kate Greenaway and Walter Crane clearly had a strong influence on the designs in our collections.

The design above clearly mimics Greenaway’s style. It epitomises the idealised childhood of the time – well-behaved, flaxen-haired children frolic unsupervised in a colourful, pastoral idyll. Their world is unblemished by signs of work or modernity; their play is neat and innocent. Children surrounded by these designs surely could not help but follow their example, as Smiles hoped.

Image: In a pattern book produced by the Kirkcaldy Linoleum Company, 1876 – c.1900. Though the colours differ from Crane’s wallpaper, the rest of the design is identical. Though most of these nursery rhymes have stood the test of time, the central song ‘Letters to Queen Anne’ appears to have faded away from the nursery in the 20th century. FIFER:2022.0150

Another theme favoured by interior design writers, consumers and manufacturers alike was nursery rhymes. This design by Walter Crane was commissioned by Jeffrey and Co. in 1876; examples of this paper – both in a predominantly blue and yellow colour scheme – survive in the collections of the V&A and the Cooper Hewitt Museum. We don’t know exactly when it was adapted by the Kirkcaldy Linoleum Company, but the fact that it was is testament to its popularity.

Pictures in rooms used by children served the same purpose then as they do now: to provide bright and colourful memory aids to assist learning and lend rhythm to group games and activities. Children living in industrial cities might not venture into a Greenaway-esque countryside, but they would still learn to tell a cow from a spoon in a well-appointed Victorian nursery, as well as maybe learning a bit of the alphabet.

All of this together meant that, from the mid-19th century, the physical reality of the Victorian home – its fixtures, fittings and decoration – was seen as an essential to the moral, intellectual, and physical health of the nation and its Empire. While the interior home was important, this project started from the bottom up – both in terms of beginning in childhood, and beginning with an appropriate floorcovering. Given the high stakes, is it any wonder linoleum companies designed products specifically for the nursery?

_________

This blog was written by Lily Barnes, curator working on the linoleum project Flooring the World (2022-2024). Flooring the World is a two-year project exploring the history of the Fife linoleum industry. It is funded by the Esmée Fairbairn Collections Fund, which is run by the Museums Association, funding projects that develop collections to achieve social impact.

If you have any questions or information you’d like to share, you can get in touch at lino@onfife.com