As part of the Flooring the World project, we are looking to actively improve our linoleum collections. This means rehousing the objects we already have, conserving those which need a bit of TLC, and researching those we know less about. It also means welcoming new objects into the collection and, to celebrate Scottish Archaeology Month, we wanted to tell you all about a recent addition.

Resin. FIFER.2022.0639

This lumpy orange stone was found on a beach on the shores of the Firth of Forth by a schoolboy in the 1970s, who initially thought it was a piece of amber. It was sent to the National Museum of Scotland, who told them that – instead – it was actually a large piece of resin.

Now, this is where the archaeology comes in. A lot of us, when we think of archaeology, imagine trenches dug in fields or roads, with lots of hat-wearing, hard-working people toiling through the mud to find Roman coins, Celtic bones, or – more usually, as several archaeologists have told me – more mud, and maybe the odd chicken bone.

In fact, this is just one type of archaeology. But, archaeological material can be discovered in lots of different ways. Artefacts can also be revealed by chance; washed up on beaches and river-banks, or exposed by storms of flooding damaging the landscape.

When we find something in this way, the challenge is then to work out how it came to be where it is. Did it enter the water way, and then get moved by currents to where you found it? Or was it buried (by accident or on purpose) and then exposed by erosion? And, then, a second question: how old is it? Has it been making its way to the beach for centuries, millennia, or just days?

These questions are more difficult to answer on the tideline than on dry land. If an object or site has been exposed by extreme weather, archaeologists may only have a short amount of time to carry out their investigations before the area is further damaged or completely destroyed. Finds will have to be quickly catalogued and removed, as any clues left unnoticed will be washed away. This was the case with the Lundin Links burial ground, which was exposed by storms shortly before our resin was found (which you can learn more about here).

Alternatively, if an object is washed up on a shoreline then we have no clues from its surroundings to tell us more about it. When removing something from the ground the depth at which is it buried, what is above and below it, and where it is all tell us something about it. This is called its archaeological ‘context’. If we don’t have this, we have to get more creative, and look at the object itself.

So, to start with, what is resin? Resins are viscous liquids which are secreted by plants when they are damaged to protect them from pests and disease. The thing that we call ‘amber’ – which the schoolboy who found our resin thought they had stumbled across – is prehistoric resin which has become fossilised and turned into stone. It starts life as resin and – as Jurassic Park taught us all – ends up decorating the canes of eccentric millionaires who use the mosquitos trapped within to unravel the genetic codes of extinct megafauna.

But, if that doesn’t happen, resin can be a useful raw material in a number of different industries. If you’ve ever played a violin, viola or cello, you’ll have used a resin to prepare your bow. If you’ve ever been second in line to offer a gift to Jesus Christ, you’ll have opted for a resin known as frankincense. And, if you’ve ever made linoleum, you’ll have used resin to create the thick, waterproof substance which makes up the surface of the Fife’s favourite floorcovering.

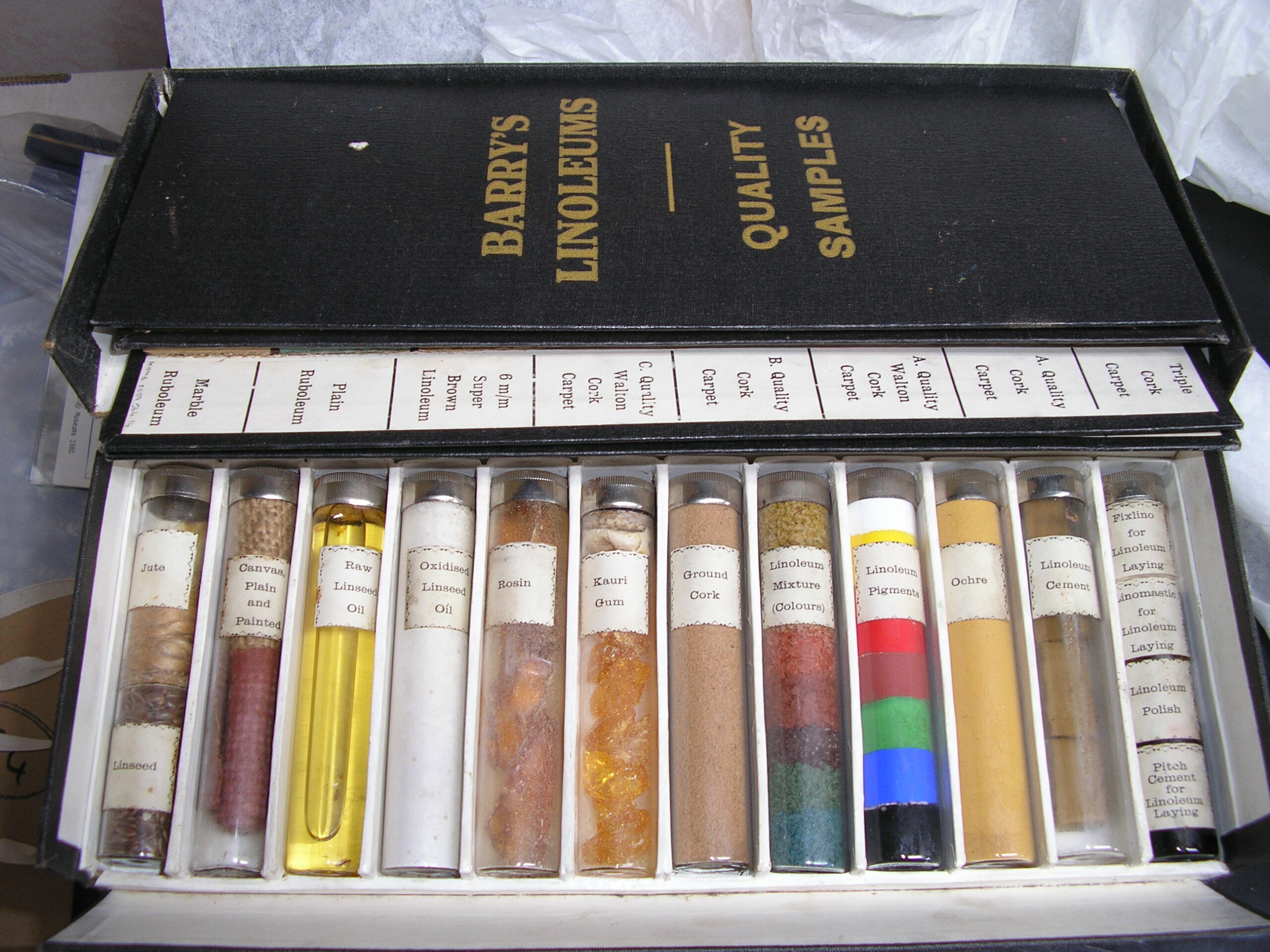

This sample case contains different materials used to make linoleum, including resin, fifth from the left. KIRMG.2007.564.1-17

This, we think, is how our piece of resin ended up Forthside. During the 1960s, the Fife linoleum industry suffered several losses. Perhaps most significant was the decision of Barry, Ostlere and Shepherd – Kirkcaldy’s second oldest and second largest linoleum manufacturer – to cease all production of the floorcovering in the town, relocating production to Staines, Middlesex.

This change had an enormous impact on the shape of Kirkcaldy. Up until the end of the 1960s, the town had been dominated by linoleum factories – generating the ‘queer-like smell’ which they town became famous for. In particular, the area around Kirkcaldy galleries was filled with Barry’s buildings.

Newspaper cutting from the Local Studies collection at Kirkcaldy Galleries.

Between 1969 and 1970, all of these buildings were demolished. In addition, several buildings belonging to Nairn’s linoleum firm – including the original ‘Nairn’s Folly’ floorcloth factory – were also destroyed. The rubble and waste material generated by the demolition was deposited at Pathhead, to ‘build up the beach’. With so much linoleum related material so near to the beach, we suspect that this may have been when our resin entered the river Forth, turning up on the shoreline not long afterwards.

You can see this object – and learn more about the linoleum industry in the 1960s – in a temporary display in the Moments In Time Gallery, Kirkcaldy Galleries until 27 October 2022. You can also check out our blog post about the display here.

_________

This blog was written by Lily Barnes, curator working on the linoleum project Flooring the World (2022-2024). Flooring the World is a two-year project exploring the history of the Fife linoleum industry. It is funded by the Esmée Fairbairn Collections Fund, which is run by the Museums Association, funding projects that develop collections to achieve social impact.